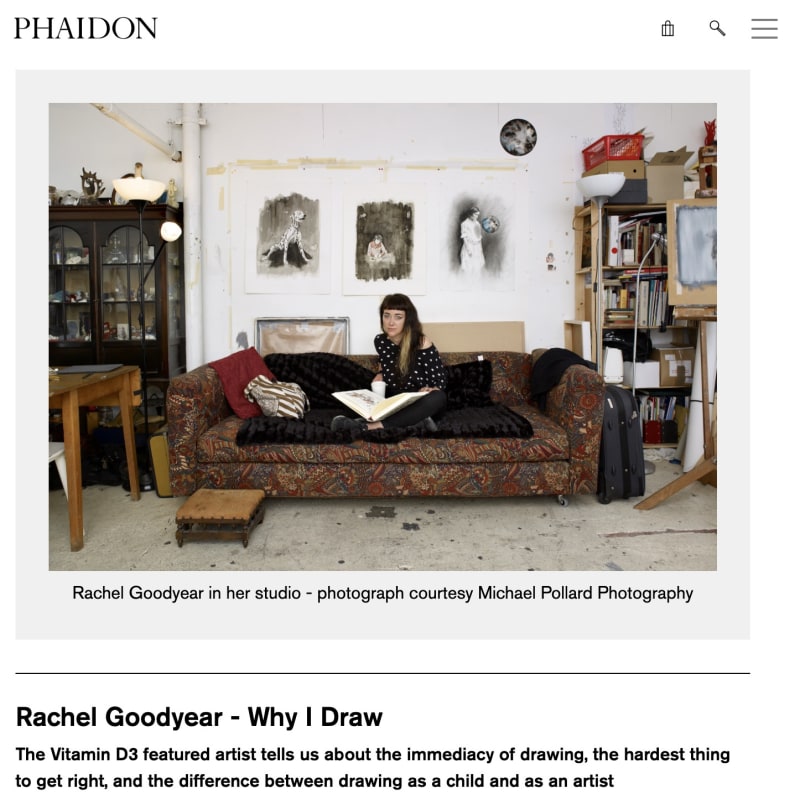

The Vitamin D3 featured artist tells us about the immediacy of drawing, the hardest thing to get right, and the difference between drawing as a child and as an artist.

Rachel Goodyear’s drawings – and her wider practice – invite us to be swept away, led, with childlike innocence, to a world of celestial mystery, psychological abstraction and curious dark rituals. In her intimate and delicate works on paper – small enough to necessitate close-up viewing – we find an ensemble of different characters, contexts, situations and actions.

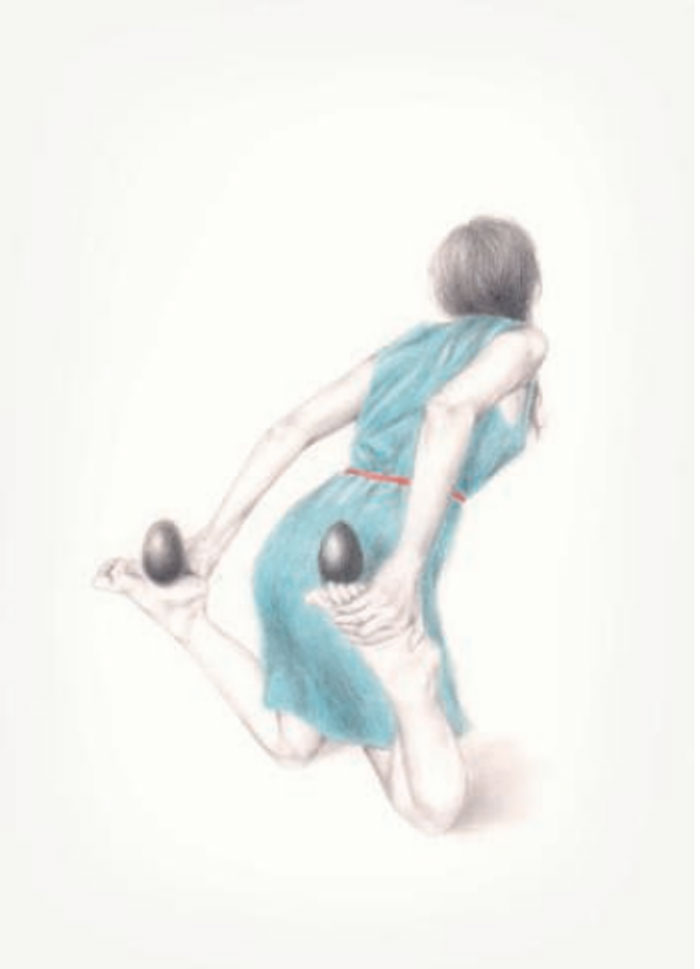

In works such as Balancing (2019), we see a woman of roughly middle age rendered in soft, almost brush-like lines of pencil and pencil crayon so that her outline is hazy. She has been contorted into a near-impossible pose. This is not a yoga posture, nor a torturer’s ‘stress position’; rather with two silver eggs balanced on the figure’s upturned heels, this is something operating entirely by its own set of rules.

Giving it a basic reading, perhaps this could be seen as a comment on the notion of female fertility? The eggs standing in for ovaries, the female body constricted biologically by their presence, her back turned trying to ignore them yet all the time shaped by their presence? However, in Goodyear’s practice things are not that simple and no one image stands alone, each one linking to the next. One must move on to find clues to her larger thoughts. It is when we assemble Goodyear’s pictures together in our minds that we start to see her broader interests, namely interior psychological conditions for which she is not trying to portray a static illustration but rather a dynamic state that one might come in and out of.

Goodyear is one of over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing, our new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing featuring over 100 artists. We sat her down and asked her a few questions about how, why and when she draws.

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? I’m Rachel, I am an artist. When I am not physically making drawings I am always thinking about it. Right now, as I imagine for most, the current pandemic and political landscape is constantly on my mind. As I write this, the UK is exiting the EU and current safety restrictions continue to keep us physically apart, and the world has never felt further away. As this year has been one of various versions of isolation, my thoughts have been very reflective, trying to navigate the uncertainty, with a sense of positivity, to hold onto all I value and love.

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? I would describe my drawings as ‘fragments’ or ‘captured moments’. They are predominantly figurative - mostly images of solitary female figures, either in preoccupied states of contemplation, or undertaking unexplained tasks with determination. They often interact or are even fused with flora and fauna. I like to refer to natural history, with all of its harmonious and parasitic relationships and characteristics, to suggest notions of the psyche and being human. So many of my drawings often suggest an ‘in-between’ state, and maintain a deliberate ambiguity, like a breath between the before and after.

I love the relationship between the immediacy of pencil on paper and the language that runs both visually and through the materials themselves. For me the surface of the paper is like a permeable threshold between worlds, which can be pressed through from both sides. When drawing on paper, I am immersed in imagined space, considering each image I project into it as glimpses that may be rising up from the subconscious. Each holding this possibility that they can spill off the page, whether this is a suggestion of something occurring just beyond the edges of the paper, or physically entering into our realm through installations and hand-drawn animations.

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? I think drawing is always being reassessed and discussed - that is one of the beautiful things about this discipline. Drawing blurs so many boundaries and its language can flow through many forms and approaches. This past year, in particular, has seen the act of drawing take on a new relevance in so many people’s lives. It has been both a creative and meditative outlet for so many during difficult times.

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’? The challenge within each piece of my work is to get the balance just right. Within each drawing, the ‘before’, the ‘after’ and the ‘meaning’ are not fixed. There’s often a sense of a macabre undertone finely balanced with a notion of playfulness and beauty. And there are so many factors throughout the processes that can tip the balance.

There is a starkness to many of my drawings, yet behind each piece are so many thoughts, ideas and versions. It is a process of honing and stripping each to the bare essentials, where a fine balance can hold enough intrigue and information, whilst maintaining a deliberate ambiguity. This ‘balance’ may be a slight alteration to a figure’s posture (which can evoke a very different feeling), or a harmonious flow in the composition, to the approach of materials - for example the decision in each piece whether to add a little colour as a discreet accent or a textured flood.

This is a visual language I have been developing over years, yet it has no fixed formula and I have learned to understand instinctively when the balance is not quite right. This sometimes means abandoning a piece I may have been working on for a long time and starting over again - this is all part of the process.

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? Definitely. Drawing can satisfy a yearning. It has always been a way for me to translate thoughts made up of half-forgotten dreams, memories and fleeting images into a visual form, from the most immediate and raw sketches to the intricately worked. I love that direct contact with the materials. Drawing can be both tender and aggressive, from the lightest grazing of the surface, to putting your whole weight behind a graphite stick. This application and easing of pressure, the graceful movement of lines, the continual adding of marks has such a beautiful rhythm to it, and when immersed can become wonderfully meditative. Every mark is a record of a moment in time, a movement and a gesture. Beginning with the faintest of outlines, I never fail to be excited to see a drawing develop as I work layer by layer from light to dark - appearing from a ghostly image into clarity.

Can you explain the difference between drawing as a child, something we can all relate to, and drawing as an artist - something must of us cannot? As children, our drawings would have been expressions that would be judged on their own terms of satisfaction, with the freedom and innocence to draw instinctively - anything from a dense scribble to creating imagined worlds. I think the magic of this begins to fade as we become aware of others’ critique, or our self-judgement begins to ask ‘is this a good drawing’ which can sadly, sometimes, overtake the instinctive urge to draw. Drawing as an artist involves a process of understanding your own voice and vision within that critique; to develop an understanding of not only the language of your own drawings, but also where they sit and connect contextually and historically. Drawing as an artist, or working within any discipline, is a continual process of creating and reflecting.

It took me time, as I developed as an artist and began to understand both the visual language of my own and of others, and recognise the threads and influences that connected them. Over the years, I have learned to appreciate and learn how to develop my processes where there could still be room to draw instinctively, whilst continually questioning and reviewing what I am creating.

What do most people overlook when they attempt to ‘assess’ drawing? A couple of things immediately come to mind - qualties that may be overlooked, yet make drawing so unique. In the context of other disciplines, there have been many times historically when drawing was overlooked as having a preparatory function rather than a discipline in its own right, with its own beautiful and fluid language. Another element that can be overlooked is the power of the ‘unfinished’. When a line, mark or image appears to end - whether abruptly, or fading out - it always holds a sense that it can lead somewhere else. Within drawing, there is as much importance and meaning held within what isn’t there as is present on the page. Drawing has the power to fade to nothing whilst holding a promise (and to spark the imagination) of what could be beyond those marks and the edges of the page.

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? My favourite place is my studio - it is like a walk-in sketchbook and a world in itself. However, I have begun to understand over the years that there are particular psychological states, and recognition of how I move through them, that help me to find my perfect place to draw. And for this, the most important ingredients are pockets of uninterrupted time.

I regularly create drawings from a ‘stream-of-consciousness’ - this can be quite frantic - where one drawing will immediately lead onto the next - and a place where many of the initial raw ideas come from. This can be quite a tricky psychological place to get to, as it involves transcending that critical part of my mind, where I can give myself the freedom to see what will emerge, without judgement, before I ‘return’ to review and explore the possibilities of how they may fit together and what they can lead to next.

And when I am creating the more refined and intricately worked pieces, I am drawing at my best when I am immersed, when the rhythm of the mark-making is set, and instinct and the subconscious are at play as much as conscious decision-making.

The perfect psychological place for me to get to is when my mind can freely move back and forth in and out of that meditative state. A pendulum of transcending and reporting back, repeatedly.

You can see more of Rachel Goodyear's work at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London and on her instagram @rachel_goodyear Meanwhile, Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing featuring over 100 artists including: Tania Kovats, Rashid Johnson, Rebecca Salter, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Deanna Petherbridge, Christina Quarles, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, and Emma Talbot is available now. We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.