“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,” Virginia Woolf wrote in her famous essay on the subject, which discusses the subjugation of women in the home. Pippy Houldsworth’s beguiling multimedia show “Breeeeze” brings together four artists to consider the ambivalence of domestic space, so often gendered as female. “Breeeeze” is the brainchild of Stefanie Heinze, a Berlin-based painter on Houldsworth’s roster who participated in the Saatchi Gallery’s group show “Known Unknowns” earlier this year. Heinze’s exuberant semi-abstract paintings and drawings are here juxtaposed with the eerily calm figurative canvases of German painter Annika Kleist and Israeli-born Orr Menirom’s video Homewrecker (2015-18) showing viral clips of brides throwing bouquets that morph into rocks hurled by protesters.

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,” – Virginia Woolf

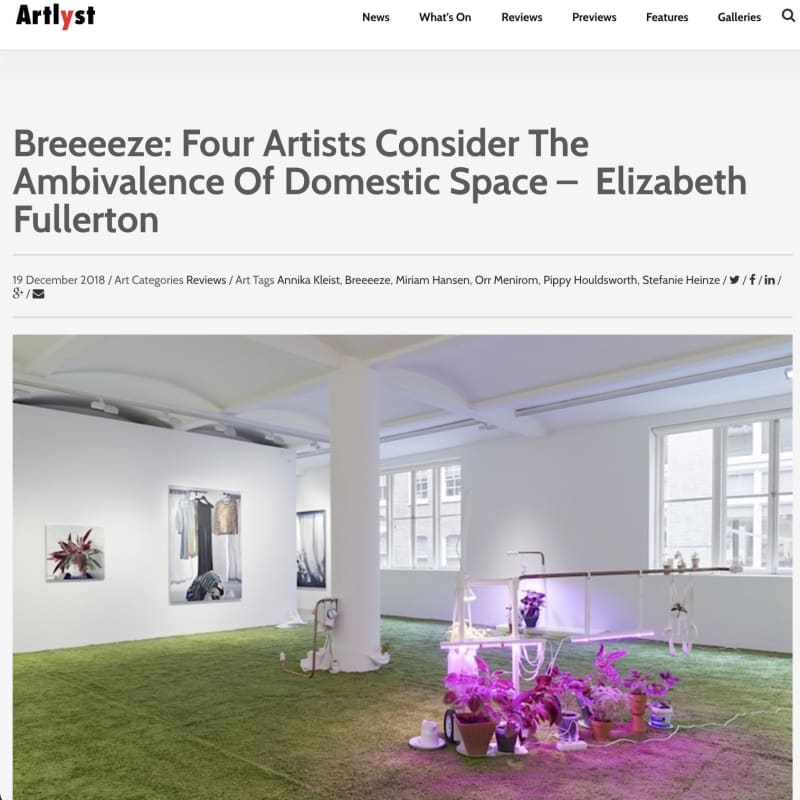

Norwegian artist Miriam Han-sen, meanwhile, has turned the space into an indoor garden with a lush grassy carpet and a sculptural installation of plants that are stationed like sentries at different points, guarded by protective structures. “I kept thinking of safe space, what it means, and how the works overlap in that sense,” Heinze told me in an interview with Kleist, Hansen and Menirom, with whom she studied. “The juxtaposition of the strange and the ordinary connects our works too,” noted Kleist.

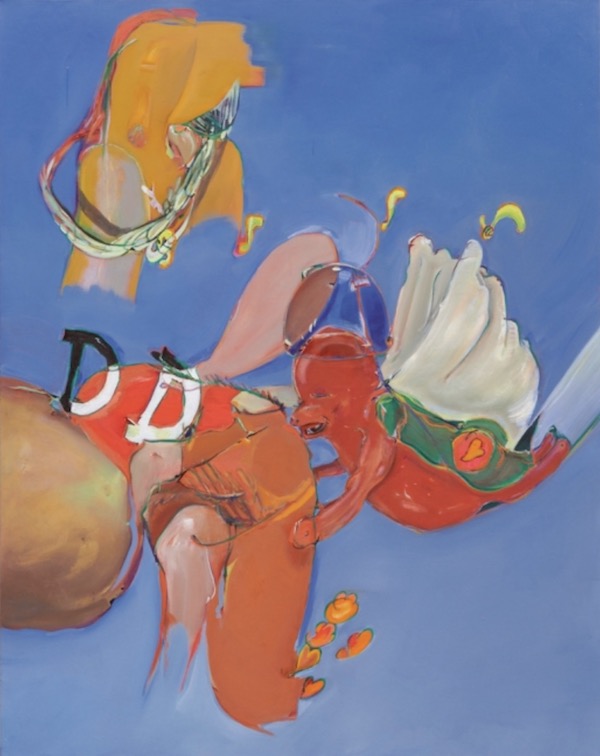

Heinze paints mostly on a large scale, throwing intense colours, letters and occasional body parts into the mix. “My interest is between low and high culture,” she says. Nothing is explicable or predictable. A disembodied penis soars through a swirling, vibrant chaos of half-recognisable forms in Fly (By) (2018). Random objects perpetually emerge and recede in the galactic maelstrom of her works – a pillow with a staff through it, a bathtub, a winged red sausage creature embracing what resembles an internal organ, a potato.

In her 2018 painting Vigilant-Vertical (The Sentinel’s Arrangement), green liquefying tendrils threaten to engulf the canvas, echoing Hansen’s plant installation and Kleist’s plant portrait on the opposite wall. “The painting has this dual layering of something natural and the opposite of natural, like a toxic green, and behind that you have some weird nothingness going on. That is the very scary part,” says Heinze, who mostly paints from drawings, allowing her imagination to lead her where it will. “So I wonder afterwards how much your subconscious just does things on its own,” she adds.

Motifs such as fingertips, bottles and wings recurred for a time in her work, to be succeeded by others. “It’s about integrating perverse, humorous actions into the world to get rid of some of the stiffness and messed up roles. And there’s a safe space in there,” Heinze notes.

This motif is picked up in Menirom’s powerful video Homewrecker, which the artist started working on in 2014 when she was preparing to get married and Gaza was under attack from Israel. Her social media feed was constantly filled with viral videos of weddings and images of protesters. “To me, the bride and stone represent the invasion of the political into our most private intimate moments. I’m questioning: can there be a non-political moment, can we make a home without a stone in today’s reality?” This tension between individual joy and collective anger is highlighted in comical scenes of women scrambling to catch the bouquet in the ritual tossing, which melts into clips of violent civilian demonstrations, all jarringly set to a romantic pop song.

The second part of the video is taken up with a narrative about a desperate bride who can’t locate any photos of her wedding, which poses the question: must an event be recorded to prove it even happened? In the third and final segment of the film, an idealistic gesture is made to reverse the hurling of brides and protesters and rewind history. “I’m interested in the language of images, the way we make sense of the world and how social media has changed the way we represent war,” says Menirom. “The gaze from outside is not possible anymore now that people film war zones on their phones, so what does that do experiencing that through someone else’s eyes?”

Annika Kleist’s dreamy, naturalistic paintings (all 2018) shut out the conflictive world beyond the window, focusing on the intimate space of her own home. Like the Danish nineteenth-century painter Vilhelm Hammershoi, she evokes psychological states through portraits of interiors. Her painting Contra-jour, for instance, depicts the silhouettes of plants on a window sill, covered by a thinly drawn curtain that seems to be tugged by a breeze. The soft palette and gauzy texture of the curtain suggest tranquillity and repose yet, as Kleist points out, “you can be isolated there too. You can be sick, you can dwell on your fears, undisturbed by other people.” A second canvas, Skim, shows clothes piled up on a chair, while others hang like a second skin against curtained windows. Her third painting, Early Afternoon Pose, bestows a sense of agency on its subject, a prayer plant. “It’s decorative, but it comes originally from the Brazilian rainforest and moves constantly,” says Kleist. “The leaves go up at night and down in the day and it makes tiny noises in the flat. It’s a living being somehow, not just a thing and it’s like ‘okay, I’m not alone here’.”

In his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny, or literally Unhomely) Freud conceived the term to describe the sense of unease when inanimate objects are brought to life. Kleist’s hanging clothes and plant convey the unsettling sensation of presence in the room, which also ties in with Hansen’s plant installation which has special lights and white railings evoking hospital equipment. The artist began collecting “these individuals”, as she calls her plants, six years ago and has encountered a community of fellow plant carers, who treat their charges with the same respect as pets and with whom they form an emotional, albeit one-sided, bond.

Hansen created the curious white apparatuses with straps and handles to ensure the plants’ comfort during transportation. Made of leatherette and foam, there is something decidedly fetishistic about them and Hansen admits she is uneasy about her role in tending the plants. “It’s an attempt at these empathetic gestures of creating this ideal space somehow but it’s very faulty, it’s tragic. At the same time, it’s also a bit excessive, creepy I guess,” she says. While the plants dominate her life, Hansen appreciates the fact they compel her to work in a slower timeframe. “I find it a very calming thing because I can’t force them. There’s a limit to what I can do other than encourage a certain growth,” she says.

Embedded in the installation, and in this show as a whole, are questions about saleability, longevity and decay – of artworks and also ideas. Nature versus artifice, refuge versus risk; despite their different styles and media, these works share surprising affinities, making for a rich dialogue around the under-appreciated domestic sanctum.