Between Abstract Expressionism and the so-called Leipzig School (where Heinze was taught), there is certainly a lot to digest. These are two significant points of reference, defining the field in which Heinze operates, and which she manages to turn into a bloated syntax of garish figures – “ciphers of plenitude,” as T. J. Clark once called them in his defense of Abstract Expressionism. Heinze’s paintings begin as drawings, so there is no mistaking her gestural canvases as being in any sense unmediated or direct (would anyone anyway?). The paper designs are small, intimate even, and they run through the gallery in glass frames perched on pedestals, a delicate pacing within the array of sizable works on view. There are no interior exhibition walls erected in this bright cube of a space; rather, Heinze has chosen to mount the paintings to the structural walls of the gallery, so that they sit within the architecture, rhyming with its rectangular elements – window frames, walls, door frame. One notable exception is the playful Rise & Plummet (boy full of ambition) (2019), mounted to a central column directly across from the gallery entrance, which hangs so that the reverse of the canvas, its “belly,” is exposed.

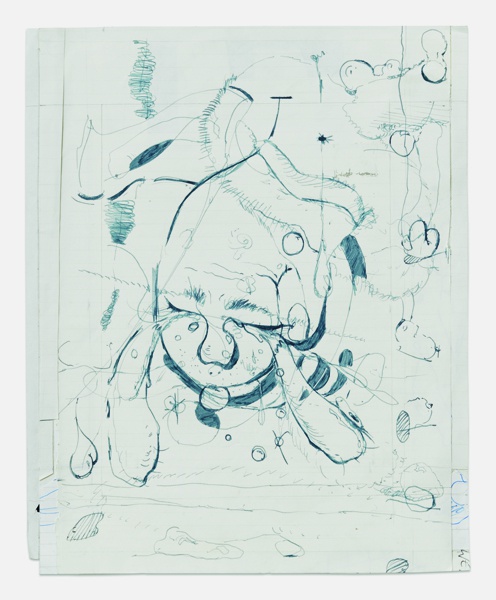

There are purples, bright pinks, flesh-colored beiges, and a heavy presence of dark outlines and contours on display. Heinze’s forms live within the contours of her drawings, but their translation to paint is a messy one; partly improvised, partly travestied. The colors are overwhelming, as is the paint handling; that is Heinze’s intention, I believe. There is too much going on. The pictures hold together as paintings, but they are more decomposed than composed, where the paper of the designs introduces a collage-like organization of pictorial space whose individual moments of figuration are subject to playful and sometimes aggressive revision in paint. The outline is shared by both mediums – drawing and painting – and marks a specific genealogy in postwar painting of how it is that one organizes a surface. For Heinze, the drawings already map the organization, as in Odd Glove (Forgetting, Losing, Looping) (2019). The prearranged design of the drawing O.T. (Odd Glove) (2018–19) means that for Heinze, color and surface treatment can begin to eat away at the constrictive pull of the composition.

The contrast in size between the tiny paper drawings and the massive canvases makes the bigness of the paintings all the more outrageous. It is Heinze’s scrawling lyricism in works like 1$ Face-Off and Insider Trading (Gloved) (both 2019) that summons the ghost of Gorky et al., shot through with comic lettering in High Potency Brood (2019). Underlying the best of these works is a turbulent wind that sets the whole play of figures and forms in motion. In the titles just mentioned, one hears the ubiquitous siren call of capital, though the distance between the context of the petty bourgeois New York of Abstract Expressionism and present-day Berlin seems impossible to bridge. Inversion makes more sense than legacy, then: the world on its head. Paintings like a 2 sie (2018–19) offer proof of this reversal of a macho millieu teeming with florid gestures and the allure of alloverness. If art in 1950s New York courted banality, according to Clark, today the inverse could be argued, where it seems banality (particularly celebrity) is courting art – everywhere. In lieu of the petty bourgeois interior that Clark frames as Abstract Expressionism’s context par excellence, Heinze uses the large, overdone, overworked painterly surface to stage a drama in which the humdrum appropriates the haughty, and the ordinary the self-important. Maybe it’s only in works like Caress (2019), hung above the entry to the gallery, that we can witness this struggle at all, suspended as it is in paint, held in front of us for inspection. Or, perhaps, it is only a myth of painting that makes us hold desperately to the idea that such distinctions between the high-minded and the tacky exist.

Look closely, and as the compositional clutter moves out of view, Heinze’s technical ability comes into sharp focus. Here, inside the patches and plunders, between the skeins of faces and bloated organs, Heinze is hiding. The back and forth between the design of the drawings and their caricature in paint is where perception and deception barrel into one another, where forcefulness flops and the paintings enact a turgid performance that empties the pretentions of gesture and action, turning their language of wholeness and sincerity into a distended stomach, or face, or some other fragment of the body. Heinze’s worked and reworked surfaces are a funny place to hide, for the paintings refuse depth at almost every turn. But hiding is something that Heinze, and some other painters of her generation, are in fact practicing, whether it is their stated intention or not.

This is not the New York School, of course, despite my recourse to Gorky, and to Clark. Heinze doesn’t need them. They are my guideposts for the kinds of questions her work raises, like them or not. M.I.A. is a more appropriate reference than Morty Feldman, but this fact does not erase the background of that very class (petty bourgeoisie) to which these paintings are addressed. Large, gestural pictures have served as the history painting for this class, and while the banal has long since devoured the field of any cultural practice, there’s no reason to believe that the forms and rhetorical language of this armchair of the middle-class (painting) cannot offer a space for perversion, irony, and a small pang of indigestion. On Gallery Weekend in Berlin, where the petty bourgeoisie faced off to stand alongside the nouveau riche and others, Heinze was addressing her audience like a salon artist to their public. What we cannot know, of course, is whether anyone was paying attention.