We speak to Stefanie Heinze ahead of her first solo show at Gallery Weekend Berlin about her playful paintings steeped in surprising meanings.

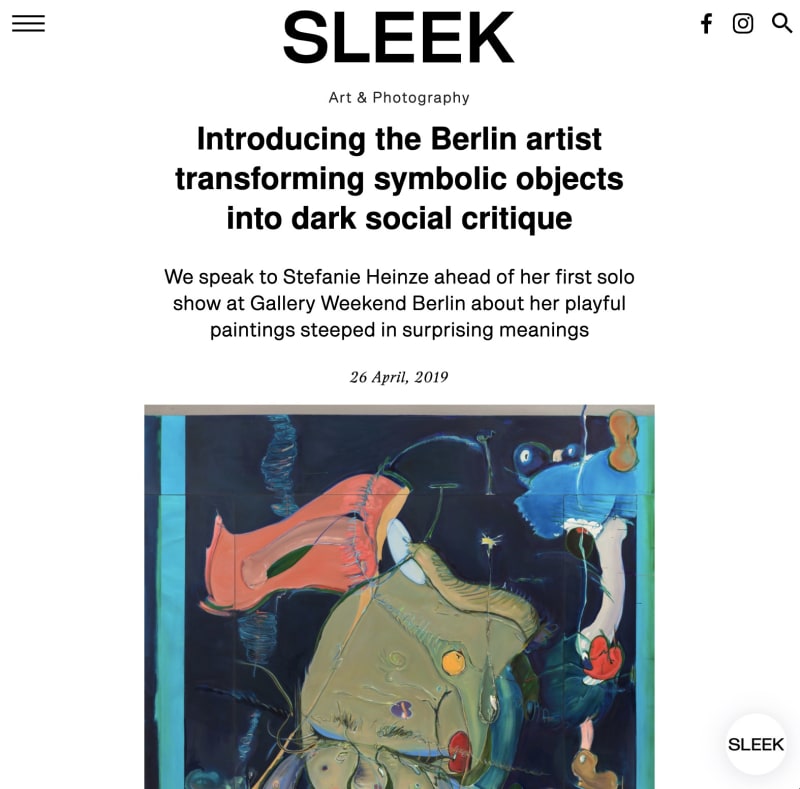

On the farthest wall in Berlin’s sunlit Capitain Petzel gallery is a large scale painting of a strange floating creature. Its eyes are downturned, tightly shut with a slash of bright blue across the lids, tears flowing outwards in sad watery drips. It’s an enchanting painting: sorrowful and sweet — it’s impossible not to be touched by its strangeness and sensitivity at the same time. The painting in question is the title work in Odd Glove (2019), the first solo exhibition by the Berlin-based artist Stefanie Heinze, opening tonight as part of Gallery Weekend Berlin. And this wistful, melancholic thing is, as you probably didn’t guess, an oven glove.

In general, it’s not so easy to guess anything about Heinze’s paintings. They are like nothing you might have seen before. The glove, with its doleful, human expression, is an uncanny thing, yes, something like what the Surrealists might have done, but it’s also playful and cartoonish and somehow far more interesting because of that. Heinze, who studied painting at the University of Leipzig, is quick to tell me that she doesn’t have any inspirations. There are things she likes — painters such as Rose Wiley for example — but really she just “kind of ended up doing it that way.”

There is a rebellious quality to Heinze’s work. Her canvases, populated with flaccid penile shapes, fudgey liquids and weird anthropomorphic forms, seem to run on instinct and intuition rather than any didactic or historically-informed concern. “I don’t really care about a proper style in painting. But I do care a lot about how I want to see things,” she explains. “I want to take the stiffness out of how things look nowadays.” Heinze’s large format and beguilingly bright-coloured paintings begin their lives as intricate, spindly drawings, scrawled on lined paper, several of which are on view at the gallery. The drawings, which often feature collaged scraps of other drawings, offer an intimate insight into her process. Heinze regards them to be “more important than the paintings.” She expands, “I think the drawings are more personal. For many people, they don’t really understand the paintings — they just know that they like them — and the drawings explain them in a good way. But not entirely.”

Drawing from her head, based on a mixture of imaginative elements and things that she sees, Heinze is often surprised by the final result on canvas. “While I’m working, I’m mostly having fun, and then at one point, I realise, ‘Oh, this is quite intense’ and the meanings can be very heavy sometimes. There’s a lot of anger and sadness to them.” These meanings that Heinze speaks of are not premeditated — they evolve from a concoction of conscious and subconscious thought, memory and feeling, a “going inside” as she puts it.

Examining a painting like Odd Glove, it may be difficult to figure out what the “heavy” meaning might be at first glance. However, as soon as it is made apparent that this is an oven glove (from the title — Heinze’s titles frequently provide clues to her works’ greater significance), the symbolism of this inanimate object unravels. “I’m not interested in a moral topic. I think with the oven glove, I was more interested in the simple shape of the oven glove first. And then I did it with its eyes closed and tears running out.” According to Heinze, those tears are in fact male genitalia — “I don’t know if anyone sees that”— and the glove itself is symbolic of “female responsibilities.” In this way, the glove is an allegorical form, lamenting the constraints of female domesticity. For Heinze, it is a matter of critiquing gender stereotypes not through gendered figures but through the “smaller things we may connect with certain genders.”

Another painting, a 2 sie (2019) which depicts a glistening egg yolk-like shape floating amid a misty sea of objects, gives further insight into this aspect of Heinze’s work. The title relates to her misunderstanding as a child of a pop song with the lyric “A to Z”. By switching the letter “Z” with the German female pronoun, “sie,” the painting represents a new order. “I wanted to misunderstand and create like a new alphabet, maybe starting a new for women,” explains Heinze. “Patriarchy is definitely a thing in my work,” she says with a laugh.

But this concept of creating a “new order” is perhaps the essence of Heinze’s work. She refers to her approach to painting as a “newsense” — “I like to work towards something that I don’t know and some kind of fearlessness, maybe. There is also doubt in that.” Uncertainty, doubt, failure these are driving forces in Heinze’s practice. She is more interested in what happens when someone or something fails, “what happens when you put your eye on things that don’t work out?” The canvas in this sense becomes a “space of freedom” to explore the strange aspects of humanity that are far from perfect. Heinze does not want to create work that you can just walk past and forget. Instead, she hopes that her paintings suggest something that stays with the viewer long afterwards. “They are awkward images, they cannot be kept in one category. That’s what I like about them. That’s the possibility.”