Photographer Ming Smith has been making pioneering work since the 1970s. Finally she is receiving the acclaim she deserves

In 1978, when Ming Smith took her portfolio to an open call at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the receptionist presumed she was a courier. “When I returned to collect my work and the museum wanted to buy it, she treated me very differently,” she says. But when Smith heard MoMA’s offer for her work, she almost didn’t take it. “I thought I was going to be rich, but it didn’t even really cover my supplies.” A curator convinced her to leave two images with the museum for the weekend in the hope that she would change her mind. She did (her boyfriend convinced her to take the money) and Smith became the first African American female photographer in MoMA’s collection.

Smith has often been at the forefront of change. As a child in the 1950s, hers was one of the first black families to move into a white neighbourhood in Columbus, Ohio. In her 20s she moved to New York and befriended Grace Jones, who invited her to Studio 54 the first night she performed there in 1978. Smith was the first woman to join Kamoinge Workshop, a pioneering group of black photographers who, she says, “introduced me to the idea of owning the images we saw of ourselves”. Now, in her “senior years” (she doesn’t share her age), Smith is one of a group of artists finally receiving recognition from an art world becoming more diverse in its representation. But Smith, by her own admission, is a loner and only now feels comfortable to use her voice.

Smith favours photographing with a slow shutter speed. She plays with light and movement to emulate the life running through her subjects. You get lost in the blur of her images as you would in a Gerhard Richter painting. Her 1978 photograph of Sun Ra, static in a swinging, shimmering cape, with glasses reflecting the light, draws you into the moment. She captures a woman walking down a road in Senegal as her outfit billows in the wind and you feel time slow. Unlike most images of black women at the time, she is not objectified.

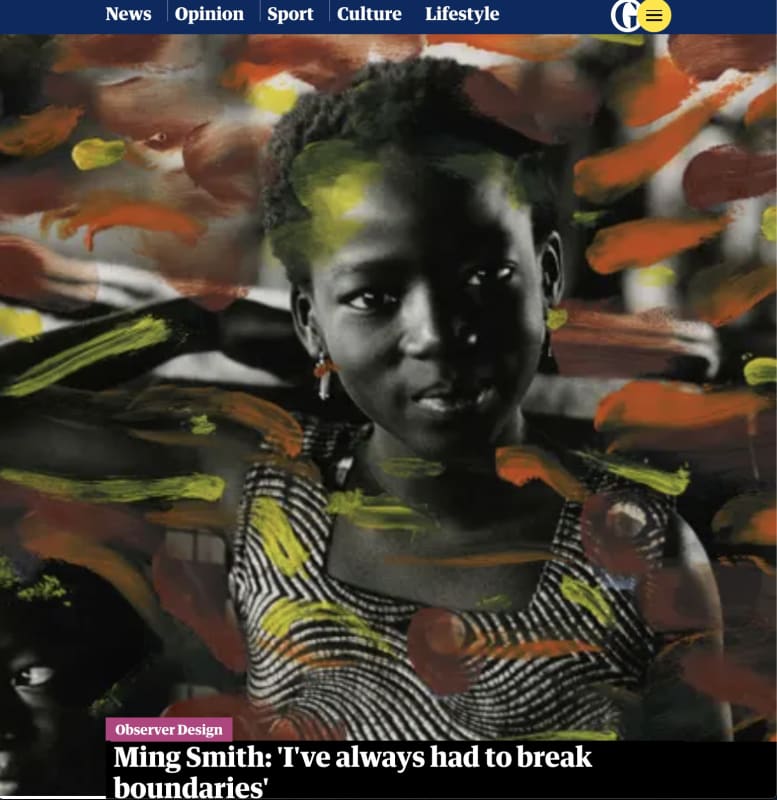

Smith talks about her love for Brassaï, Gordon Parks, Diane Arbus, always favouring candid street photography over studios and poses. But she’s interested in playing with imagery, too. She cut out an image of the writer James Baldwin’s face from a snap she took of him and his mum when she spotted them at a poetry reading in Harlem in 1979 and used it in a collage. She often employs double exposure and layers paint swirls to enhance images.

Smith has a big year ahead – despite the impact of Covid-19. Her solo show at Pippy Houldsworth is online from 21 May and she will be honoured by the Aperture Foundation in June. Later, the Whitney will feature her work in a planned Kamoinge Group retrospective, and she is working on a monograph. Much has been postponed or switched format, but Smith is calm about it. “What’s going on is much bigger than my work. As an artist, this is the way things always are – they get moved around, people change their mind. My work is here, it’s been here for years. I just have to ride the tide.”

For most of quarantine, Smith hasn’t been taking pictures. Her focus was meeting her deadline for the monograph. “For some reason, shooting right now doesn’t interest me. I was that way with 9/11 too.”

But when we speak, on 3 May, the day after her monograph deadline, she’d gone for a walk with her Leica. “I had wanted to do a project on lost jazz, and all of a sudden I saw what I needed to begin.”

Born in Detroit, Michigan, and raised in Columbus, Smith describes her childhood as that of “a real American girl”. “We loved Marilyn Monroe, ate Wonder Bread, lived through the assassination of Martin Luther King.” Her father was a pharmacist, but due to institutional racism he didn’t earn the salary of a white man in his position and they struggled financially.

Her family were into Shakespeare, and the black American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. They introduced her to art and architecture, but she can’t recall ever seeing artistic images of black people, nor did she know of any black painters. “It’s hard for my son to understand now,” she says, “but there was no internet and my history books were cowboys against Indians.”

Her dad introduced her to photography. She sat while he took light readings on her face, but he worked long hours and didn’t have time to make art. She went to Howard University, a historically black college, to become a doctor but dissecting frogs made her squeamish. She confided her unhappiness to her father. “He was of few words but he said, ‘Well, you could always be an artist’, and it just opened me up.”

Smith took a bus to New York in the early 70s, knowing no one. She had a successful career as a model, but she also carried her own camera everywhere. When a friend opened a hairdressers in a bougie area of Manhattan in 1974, he asked Smith if she would show her work there. The salon was Cinandre’s, nicknamed the Studio 54 of hair salons: Jean-Michel Basquiat decorated the chairs and Grace Jones says it’s where she had her first orgasm after a stylist cut her flat top. The exhibition gave Smith a name around town. People lined up to see it – including Roy DeCarava, the first black photographer to win a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Smith’s vision was different to the mainstream way black people and black culture were typically portrayed. “I wanted to capture the spirituality, the humanity of black people, my love for the culture,” she says. “Jazz musicians were celebrities around the world. They were loved, people identified with the music. So why then was [black] culture stereotyped as guys in the hood or poor folks on heroin?”

When Smith was invited to join the photography collective Kamoinge Workshop by founding member Louis Draper, she became the first woman in the group of New York-based black photographers. “I didn’t really think about being the first woman,” she says. “I just thought of myself as an artist on my path. I guess in my world I just go for things regardless of the boundaries, because I’ve always had to break boundaries.” She calls herself a product of the Black Arts Movement – a sister group to the Black Power Movement – who were “radically opposed to the concept of the artist alienated from their community”. “They introduced me to the idea of owning the images that we saw of ourselves,” she says.

The same year her work was collected by MoMA, Smith met jazz musician David Murray whom she married. She did the cover artwork for his albums, including a self-portrait on the critically acclaimed album Ming. She toured with him through Europe and Africa, expanding her portfolio.

The first time we speak, Smith is in the midst of selecting pictures for her monograph. A few times in our conversation I ask about an image and she wonders aloud whether to include it in the book. One of these is a portrait of Tina Turner. She says in 1984 she was invited by her “mover and shaker” friends from modelling to dance in the video for What’s Love Got to Do With It? She took Turner’s picture because she was taking everyone’s picture.

In the mid-80s, many of those same mover and shaker friends died from Aids. Smith stopped modelling and had her son, Mingus. With no representation and not being an art insider, attention in her work dropped off. Her marriage to Murray also ended.

When her parents died in the late noughties, Smith became depressed. “I’d spent my life making my art without great success. It made me think, ‘Was I doing this for them, or for me?’”

But since then, her work has been acknowledged. Her photos were in Tate Modern’s 2017 show Soul of a Nation and her work was then acquired by the Getty Museum and the Whitney in 2018 and 2019.

In 2000, she was featured in a MoMA exhibition and the New York Times highlighted her work in its review. Smith had walked through the exhibition but missed her own photograph; she was alerted to it by the curator when he spotted her leaving. “I’d thought [in the past], ‘One day I’m going to be in one of those shows, right?’ It was a big, big moment for me.”

Since then her work and name have gained increasing traction. She joined (and has since left) a New York gallery, and last year exhibited at Frieze Masters in London. Alicia Keys’ husband, the producer Swizz Beatz, told Smith he wanted to be her biggest collector. She’s influencing younger artists, too. Tyler Mitchell, the first black photographer to shoot a Vogue cover, says: “Her work shows me how to pull poetry and spirituality out of the mundane.” It’s just bittersweet for her that her parents can’t witness this.

When Soul of a Nation travelled to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas in 2018, Smith was asked to speak during the exhibition run. “I’m very shy and I’d never really spoken before. I love photography because I can say more with it than I can with my speech,” she says. “But my son Mingus was like, ‘Mom, you’ve got this, they really want you.’”

She says she wouldn’t be where she is now without Mingus’s support. But it does seem to be rooted in her, too, maybe from her own father. “I used to say to Mingus, ‘You have a big person in you and a little person and sometimes the fear and insecurity of the little person takes over: always work on the big person.’”

• Pippy Houldsworth’s XR exhibition of Ming Smith is available via the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery online viewing room and on Vortic Collect, from 21 May.