When we hear the word 'embroidery', it often brings to mind the idea of an older, refined past time. We picture beautiful, intricate patterns of flowers and views of rolling hills in the prairie. We might even imagine a Jane Austen character working on her embroidery skills to improve her marriage prospects – as any respectable "lady" should, of course. But East-London born, NY-based artist Zoë Buckman is turning the art form on its hoop. In her latest mixed-media work "NOMI", Buckman reckons with intensely personal themes of domestic life and spirituality. Playing with the juxtaposition of hard and soft, masculine and feminine, her textile canvas often bears witness to themes of violence and aggression in direct contrast to the feminine space that embroidery occupies. If you're expecting to see pretty and delicate landscapes here, you're in for a rude awakening.

Boxing gloves exuding masculine power are adorned with flowers but hung by a heavy, metal chain and vibrant text dancing across vintage material forebodes dark tales and chilling encounters. Nothing is a picture perfect piece of work. Threads come loose, stains blot the page and edges are frayed. But all is well-intended in Buckman's exploration of freedom and we caught up with the artist to delve deeper into this free-spirit and understand the breadth of NOMI's introspection.

NOMI draws on a lot of overwhelming and traumatic experiences that you went through in 2018 that was then triggered by the pandemic. Is NOMI a way of navigating through this resurgence? Do you feel like 2020 forced you to face or tackle those experiences in a different way or has a reconciliation with the past been ongoing for you?

The last several years has definitely been characterised by transformation for me, and by the process of navigating and coming through difficulty. But the experience of 2020 really galvanised that work- or rather, it gave me the opportunity to reform the context to best process my trauma and how to turn lemons into lemonade. My year started with a journey to India, a pilgrimage that I went on with my daughter in which I offered back my Mother’s ashes to the Himalayan Ganges. This was a rebirth in many ways, and deity worship and devotion became pivotal steps in my healing. Then of course I returned from India into lockdown in New York. The panic and uncertainty of the pandemic, as well as the pause, gave me a space to take all that good stuff and really bring it home, inviting in new ways that I could metabolise difficulty.

You've brought the boxing gloves seen in Heavy Rag back into your new work - why was that? How have they been reinterpreted this time?

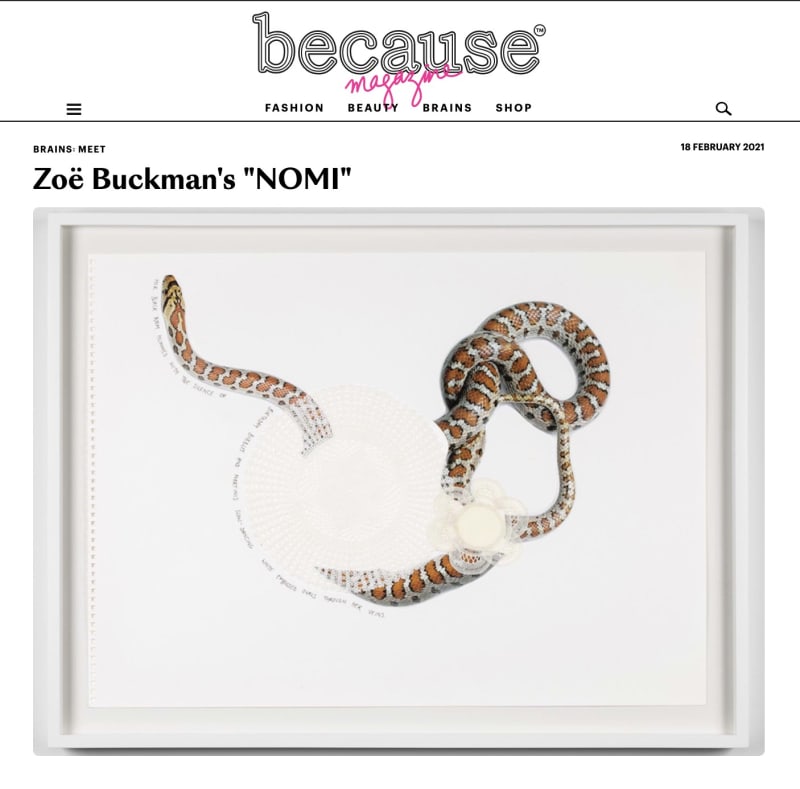

For this series I’m still examining the home, violence, the subjugation of women and the attempt to cover up what is, as well as our shared resilience - these are explored in the sculptural works that incorporate boxing gloves and domestic textiles. For the first time in my work though I’m looking a lot at wild animals and the earth. NOMI is the name I gave the shadow aspect of my psyche and she represents that inner wild force within us all. So snakes, wolves, and predatory birds are recurring motifs. I’ve brought the idea of the earth and the snake into the glove sculptures, but subtly. They are represented in the green ribbons that curl off of and fall into your creases, and the mohair threads that dangle from time turned chains into rust. The experience of scattering the ashes...the way they cascaded downstream into the sacred water in swirling patterns is explored in the work & Ganga water glistens, which I actually made with my mother’s tea towels. The way one glove is balanced on the other is very much about the experience of trying to cling to something that is slipping away, not knowing if she is holding me up, or I am holding her.

Could you enlighten us on how you source the vintage textiles and why you use vintage fabrics?

Yes! My studio looks like a secondhand shop at this point. I get a lot of the textiles from estate auctions, thrift stores, and also online. Now though, friends will offer me their family antique linens and that is always really meaningful to me.

A lot of the text in your body of work references other artist's words. What was different this time that led you to use your own text from the ongoing poem Show Me Your Bruises Then?

It’s an interesting question because I realise that I started to put my own language into the work when my mother was terminally ill, and she was a writer, so I think it was about trying to keep her legacy alive and find ways to connect with her and her work even after she passed. Using my own writing in my work definitely adds another level of vulnerability and exposure; and I think I’ve needed to wait to do that until this point in my career because with each exhibition and show, I gain a bit more confidence in myself and my practice as well as detachment to what others might think. Getting older is good for that, init!?

Brains: Meet Zoë Buckman's NOMI

Because Magazine, 18 February 2021