Kate Bryan interviews the inimitable London-born, Brooklyn-based artist Zoë Buckman in anticipation of her upcoming exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, opening Friday, February 12th.

Kate Bryan: This is a really powerful body of work, I find it really moving. You’ve started from a really tough place, dealing with grief and trauma, and it feels like the show is a physical manifestation of you working towards light. Yes, it’s tender, but also full of joy and a refusal to submit. Can you elaborate?

Zoë Buckman: Thank you for seeing that, Kate! I have definitely been on a journey of transformation due to a succession of life transitions in a short period of time: from my divorce, to caring for and losing my mother to cancer, and addressing both recent and older experiences with violence in relationship, and then of course the pandemic itself. “A refusal to submit” is so well put, and resonates deeply with me. I’ve learned that there exists within me, and within us all, a force of power, freedom, creativity, and joy that is constant and unchanged by our external conditions and experiences. I gave that force a name and persona [NOMI], as it’s helpful to me to seek out ways to further engage with her.

KB: Can you tell me a bit about your process? You are obviously someone very interested in conceptual strength; there is also a commitment to your materials – often repurposed domestic things like doilies or handkerchiefs which have this whole other life. Where do you tend to start?

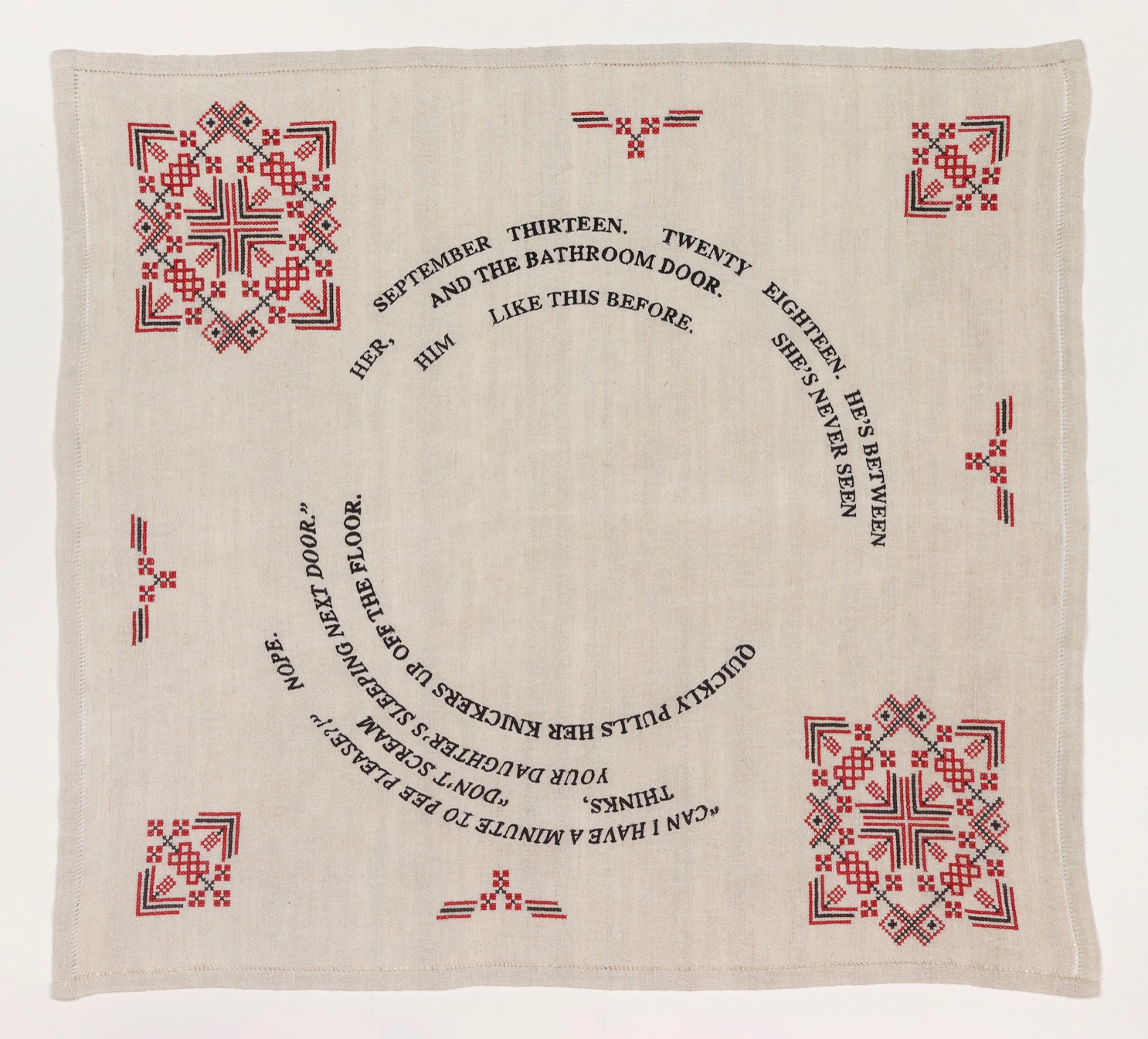

ZB: I collect vintage domestic textiles because they speak to the home and the female experience, and because they have had a life and story before entering my studio, so usually I’ll start a piece by selecting a textile as the seed for a sculptural or flat work. However, dancing around in my mind is a vast array of source material: fucked up things people have said to me, beautiful things women have shared, notes I’ve written to myself, texts I’ve read on the soul, the divine feminine, the subjugation of women etc; images and memories of times I’ve felt empowered, wild, open and vulnerable or caged. It’s all a bit of a tumble dryer and I’ll wait for a something to slip out and onto the work.

KB: The boxing gloves have become something of a signature motif for you. They walk a fine line between something performative and ‘masculine’, and something inert and ‘feminised’ – even to describe it in these terms is so reductive. You often play with norms and stereotypes around gender – was that the genesis here?

ZB: I’ve always felt I have a firm connection with both my masculine and feminine sides, and that societally we are often made to feel that we must be attached to and lead by only one, or that we cannot label them thus for ourselves, contributing to polarizing the masculine and feminine. I don’t think that progress means doing away with the idea that Yin is different to Yang. The moon is not the sun. I’m interested – personally and with my work – in exploring the exciting ways in which we are all both moon and sun, Yin and Yang, masculine and feminine, and leaning into the ways in which they intersect. You can box and also pray, fight and also cry – and life will have you doing both plus everything in between.

KB: NOMI is the title of the show and also your alter ego. There is real generosity of spirit in your making work that comes from such a personal place; is it tough to put it out there sometimes?

ZB: Yes! Sometimes it’s cathartic, and sometimes it’s triggering as fuck. Sometimes it will start as one of those and become the other. In general though, I am moved and honoured when people feel seen or advocated for in the work.

KB: You have rejoiced in the notion of the ‘unfinished’ in these works: stains mark the page, threads hang loose. There is something raw about everything which I can only imagine makes it hard to know when to stop and say ‘that’s done’.

ZB: You know that’s a really good question, because I realise that embracing the unfinished in my work is also about embracing my relationship to grief and trauma itself. We talk about heartbreak and loss as something that wounds us, and it does. We talk about trauma as something takes pieces out of us, and it does. Instead of knitting ourselves back together, I think that life might be teaching us how to live around what’s missing. Creating work where there are incomplete forms, where ink bleeds unpredictably, where I cannot control the exact formation of the wet ink on the fabric or the ways in which the threads will dangle and even tangle once framed – that’s teaching me how to surrender to what is, and love it, however uncomfortable it makes me.

KB: Can we talk about the snakes please?! As an art history geek I am so into the serpent motif and all it has meant, so what does it mean to you?

ZB: Me too! I have so much to say about the significance of snakes and continue to learn more about the different ways they’ve been depicted, honoured, or blamed in art and religion. Firstly I should state that I am frightened of snakes and yet I find them magnificent. They shed their skin and so literally represent what we are always doing here – transforming, releasing that which no longer serves us and rebirthing ourselves. They crawl on their belly and have been associated with temptation, sex, and the underworld. According to the Vedas, our life/energy channel runs through the centre line of our body, along with our spine, and there are two snakes that curve and spiral upwards, intersecting at each chakra point and ending up in the brain as the left and right cortex. Kundalini is very much about accessing that inner snake energy through breath.

KB: You have consistently explored and incorporated text in your work – the first series I encountered was vintage lingerie with TuPac lyrics sewn on them. This show is based on a poem you wrote yourself called “Show Me Your Bruises Then” – how has it differed working with original rather than appropriated passages?

ZB: It's definitely made the experience of sharing my work even more vulnerable, because I’m laying bare not just what occupies my mind and time, but also what I’ve written myself. I’m not able to fall back on the idea that “well, these aren’t my words”, and so I have to choose my words carefully, innit?! But to me, it feels more honest, and I also recognise that in the process of writing I am falling in line with my mother’s chosen discipline and therefore finding ways to celebrate her and all she taught me.

KB: I think there is something really prescient about the way you work. Your enormous sculpture CHAMP (2018), which depicted an abstracted uterus with boxing gloves for ovaries, arrived at Sunset Boulevard just in time for the post-MeToo-era Oscars. And NOMI arrives as a beacon of light in the dark of London’s third and arguably most brutal lockdown. I find artists are often culturally clairvoyant, how does it feel from where you sit?

ZB: That is such a kind interpretation Kate, thank you. It’s not something I’m cognisant of in my work, but I definitely see that in the work of other artists I admire. I think many of us are pretty sensitive folk and so are definitely sponges for what’s happening in the present moment. And because we’ve been training ourselves in how to creatively express and comment on the status quo, we can end up making work that is by definition current or contemporary, even if that wasn’t an intention, or wasn’t something we were aware of.

KB: The work comes from a personal place but I get the sense you are always thinking of an audience. It’s not some kind of catharsis in a vacuum, right?

ZB: That’s right. I don’t feel I make work for a viewer, but I also don’t make work for me. I am aware of the audience and am always trying to honour her/them, not pander to them. It’s a tricky line to toe! So I ask myself the following questions before sharing something I’ve made: Does this work need to be made by me? Does this work need to be made by me now? If yes to those, then: is this the right way to make the work? Is this work well made? (super important to me!) and lastly, is this an over-share? I don’t want to be self-indulgent, so I always ask myself that last one and try to answer it as authentically as possible.

KB: This is a real homecoming for you, your first solo show in London off the back of some really impressive projects and exhibitions in New York and LA. What does it mean to you to be showing on home territory?

ZB: Honestly it means so much to me. London is such a formative part of my identity and sensibility! My favourite people in the world are in London and it will always be a home… so to show work in the context of my home, and work within which there are depictions of London Galdem, it’s hugely meaningful to me.

KB: This is your first solo show with Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. It’s a great context, I know you love the programme – tell me who stands out!

ZB: When I first became a mother I grappled with how I could possibly attempt to be a “good mother” and a “good artist”. I consumed the work of Mary Kelly and could not get enough. I am losing my mind to be represented by the same gallery she is! I also adore the work of Ming Smith, and adore her as a woman, and am blown away by Jade Fadojutimi’s paintings. Pippy Houldsworth is a power house with a strong program of Female artists and, I think, an acute and sensitive eye. It really is an honour to part of Pippy’s program right now.

KB: Lastly, you are a very socially and politically engaged artist and person – what do you think it means to be an artist right now, in this extraordinary moment in world history?

ZB: It’s such a privilege! Sometimes I can’t believe I’m alive in a time and society where I am allowed to take the things in my heart, channel them through my fingers, and share them with others.

KATE BRYAN is a British art historian, curator and arts broadcaster. In 2016, Bryan became Head of Collections for Soho House globally.