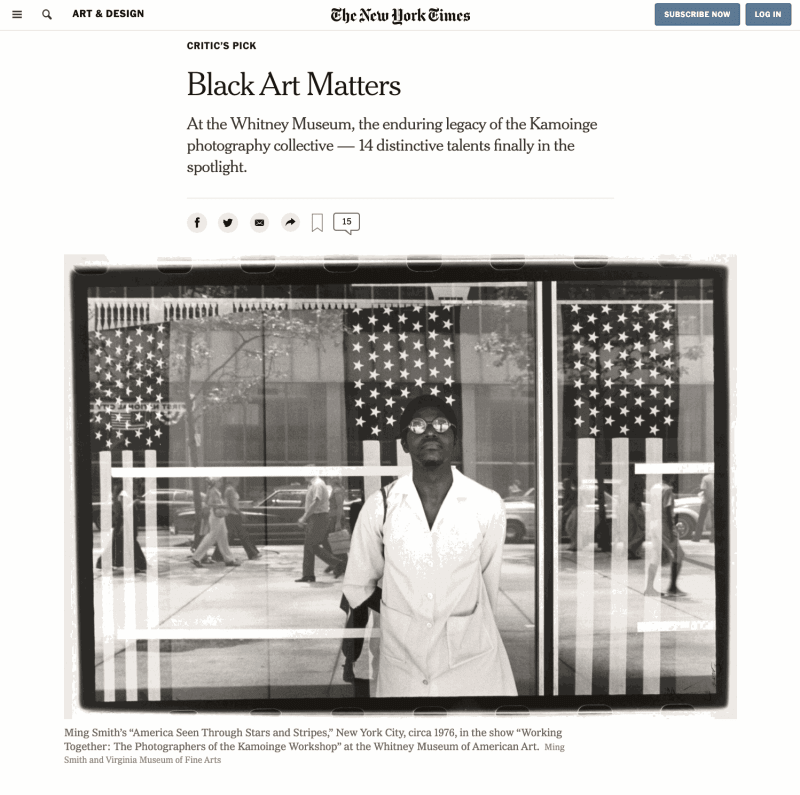

At the Whitney Museum, the enduring legacy of the Kamoinge photography collective — 14 distinctive talents finally in the spotlight.

It’s only fairly recently that the mainstream art world, which likes to think of itself as progressive, has fully begun to embrace the idea that Black art matters. Even a few decades ago, if you were an African-American artist, you could realistically expect to find your work excluded from major — i.e. white-run — museums. For you, the marketing machinery that makes careers didn’t exist. Galleries weren’t showing you. Collectors weren’t buying you. Critics weren’t looking your way.

The same art world is now in catch-up mode, “discovering” Black talent that has always been there and acknowledging rich histories hitherto ignored. High on the list of current retrospective excavations is “Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop,” a traveling exhibition beautiful to contemplate in every way, at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, African-American photographers were plentiful, but wide-circulation outlets for their work were not. With a few exceptions — Roy DeCarava, Gordon Parks — popular magazines and newspapers weren’t hiring them. And when they did it was often with the demand that they deliver preordained views of Black life in images of idealized uplift or impoverished dysfunction. The idea that their work might stand outside the news, as art, rarely arose.

The group, which called itself the Kamoinge Workshop, was formed by four artists, Louis H. Draper (1935-2002), Albert R. Fennar (1938-2018), James M. Mannas Jr., and Herbert Randall, some of whom had been members of another, slightly earlier Harlem-based collective, Gallery 35. Other photographers soon joined and the Whitney show, which spans the group’s first two decades, includes work by 14 early members. Some were academically trained, others self-taught. Most sustained themselves as photojournalists with freelance jobs and teaching gigs. Importantly, none of them drew any absolute line, in terms of value, between photojournalism and art, “reality” and what you could make of it.

Organized by Dr. Sarah Eckhardt, associate curator of modern and contemporary art, at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, and overseen at the Whitney by Carrie Springer and Mia Matthias, the exhibition is arranged by theme. But none of the themes — politics, music, abstraction, community — is airtight. They overlap, interweave.

The word “kamoinge” — pronounced kom-wean-yeh — means, in the language of the Kikuyu people of Kenya, “a group of people acting together.” As a group name it’s resonant of a period when the United States civil rights movement and the post-colonial African independence movements were running on parallel timelines and shaping Black consciousness internationally.

Africa is very much present in the show. It’s there in early 1970s photographs of street life in Dakar, Senegal, taken —- both on commercial assignment and self-assignment — by Anthony Barboza and Ming Smith, the group’s only early female member. And it’s there in work by Kamoinge photographers traveling through the continent’s global diaspora: Herbert Howard in Guyana; Herb Robinson in Jamaica, where he was born; and Shawn Walker in Cuba, where he stayed long enough to be blacklisted as a radical when he returned to New York.

That was in 1968, during a decade when racial politics was perpetually on the boil in the United States, and Kamoinge was right there for it. Adger Cowans covered Malcolm X’s funeral in Harlem in 1965. Herbert Randall had been in Mississippi for Freedom Summer the previous year. And three Kamoinge regulars — Draper, Ray Francis and Walker — appeared, unnamed and in close-up, in a cover photo for a 1964 issue of Newsweek above the headline: “Harlem: Hatred in the Streets.”

The photo was by DeCarava, on assignment in Harlem after the killing of a Black teenager by police had sparked an uprising in the neighborhood. There he bumped into three young Kamoinge artists, all of whom he knew; he himself was at that point a member of the group. He, and the white art director he was traveling with, asked them to pose as “angry.” They did; DeCarava got his shot. All involved were amused by the incident, but it neatly illustrated the kind of expedient, tied-to-the-news image-making that Kamoinge was trying to expand beyond.

If racial politics, in its many forms, was a shared burden of the group, music was a joyous cultural binder. Many members compared photography to jazz: once you had your technique down solid, you could improvise endlessly, go abstract. Some of the most beautiful of the show’s 140-plus images are of admired musicians: Ming Smith’s shot of Sun Ra as a blurred toss of gold-spangled cloth shimmering like a nebula; Herb Robinson’s portrait of Miles Davis as a glowing melt of shadow and light.

It makes sense that, through the two decades covered by the show, Kamoinge members kept working intensively in black-and-white. Expense, no doubt, was a factor: black-and-white was a lot cheaper than color. It also let them stand in the tradition of honored older photographers like James VanDerZee, and Marvin and Morgan Smith. And it gave them the option of pulling in a wide range of art-historical influences: the ghostly evocation of art from the deep past in C. Daniel Dawson’s haunting multiple-exposure image of the faces of his young goddaughter imposed on that of an Egyptian sculpture; the penumbral look of Rembrandt in the case of Walker’s work; the high-contrast abstraction of Japanese painting and film in the case of Fennar’s.

Abstraction — Beuford Smith’s self-portrait as a shadow cast on falling water; Draper’s image of cloth hung on a clothesline and resembling Ku Klux Klan hoods — is in fact, the show’s distinguishing feature. The choice of abstraction let Kamoinge artists depart from documentary depictions of the African-American community without entirely leaving it, and its political realities, behind. Abstraction let artists keep the image of Black life inventively complicated in a society, and art world, that wanted — and still wants — to nail it down.

And in the end, there’s something engagingly unabstract about the show itself, which comes across as a gathering of 14 distinctive personalities. Dr. Eckhardt’s scrupulously researched, archive-based catalog, which puts particular emphasis on Draper, is a big help in this way. So are the photographs chosen for display. You can spot the eye and hand of individual makers from across a room.

And then there are the faces in Barboza’s set of headshots of the early Kamoinge team. He produced the portraits as a limited-edition portfolio in 1972 and gave one copy of the set to each artist-colleague as a Christmas present that year. What a gift! He made them all look like stars. No surprise. They were, and are. (Nine of them are still hard at work today.) The only surprise is that we’re just acknowledging their radiance now.