A new exhibition shines a light on the long-running collective of photographers who started documenting black culture in the 60s and haven’t stopped since.

In 1973, a group of 14 New York photographers huddled into a photo studio on West 18th Street in Manhattan, posing in front of a Hasselblad camera for a group shot authored by Anthony Barboza, who stands smiling in the picture.

“I remember arranging the lighting and then my assistant took the photo,” said Barboza to the Guardian. “It’s a photo of a family. That’s what it is. A family photo.”

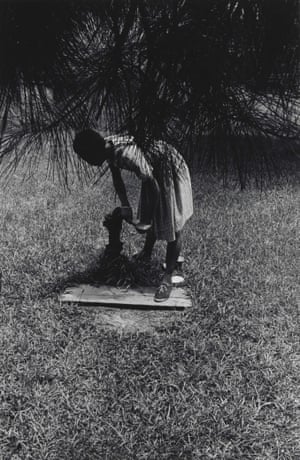

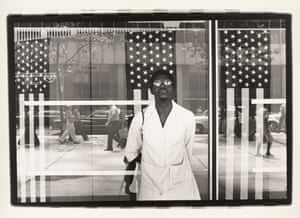

It shows the members of the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of black photographers who formed in 1963 to document black culture in Harlem, and beyond, from live jazz concerts to portraits of Malcolm X, Miles Davis and Grace Jones, as well as the civil rights movement and anti-war protests.

A selection of over 100 photos by the group are on view in a survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York called Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop, which runs until 28 March.

“The 1960s and 1970s were a time of social unrest, as ours is at this point,” said Whitney curator Carrie Springer (this traveling exhibition from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is curated by Sarah Eckhardt).

“Looking at how they centered their artwork on depicting the community as they experienced it is inspiring, at a time like now,” said Springer. “Their self-organizing work in their community represents an individual and collective truth, one which is focused on the power art can have in communities.”

The Kamoinge (pronounced kom-wean-yeh) collective all started in 1963, when a group of 14 black New York photographers came together to form a group, to trade skills and offer critiques to one another. They chose “Kamoinge,” as it means “a group of people acting together” in Kenya’s Gikuyu language. They worked to tell black stories by depicting black communities, from local neighbors to superstars, and saw their rise around the same time as the Black Arts Movement. Kamoinge photographer Adger Cowans, who is 84, always believed the group could show the truth of black lives, more so than an outsider. The goal has always been to “show people in a positive light”.

The group supported each other with critiques, debates and often ventured out to shoot together like a family, while also shooting alone too. “I did a lot of portraits of black artists and musicians in my spare time,” said Barboza who photographed Michael Jackson at 21, as well as James Baldwin and Gordon Parks.

Nine of the 14 original artists are alive today, working and living in New York, including Beuford Smith, Ming Smith and Herb Randall. After the first 20 years, the group reorganized as Kamoinge Inc, and expanded to include membership and nonprofit status, and continues today, 60 years since first founding.

As one of the group’s members Ray Francis said in 1982: “We were a group that stars fell on,” and credit observational photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks and Dorothea Lange as influences. Another member, Ming Smith, calls it: “Making something out of nothing. I think that’s like jazz.”