Jacqueline de Jong’s death is a hard notion to grasp when speaking of an artist whose life and work coursed with such unflinching strength and unbridled vitality. Born in 1939 to a Jewish family in Hengelo, the Netherlands, De Jong created a rich body of work spanning six decades across painting, sculpture, graphic art and publishing.

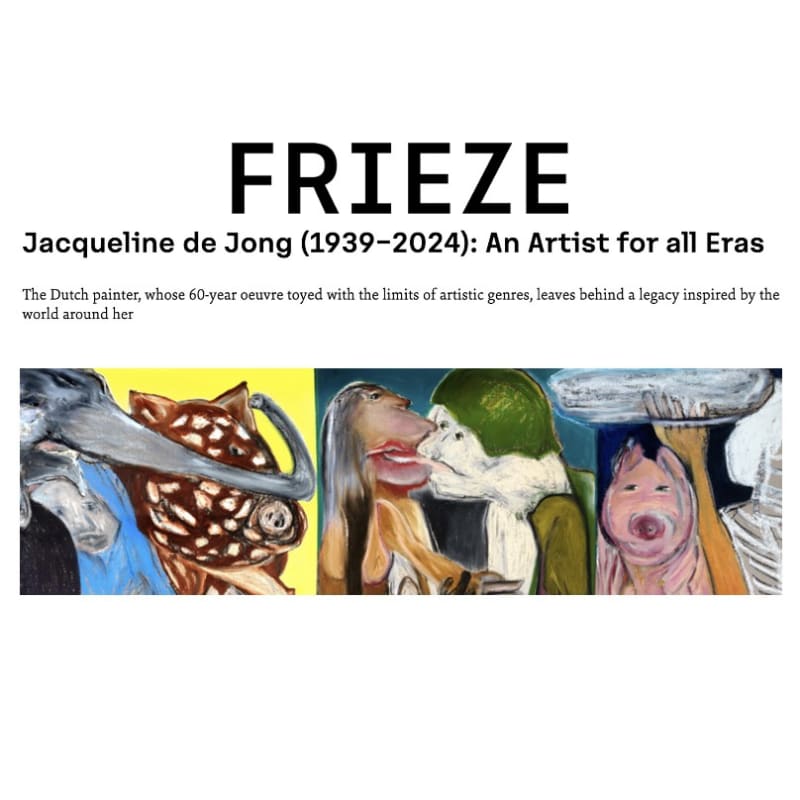

In one of my first encounters with her in 2017, which marked the beginning of our enduring personal and professional relationship, I asked her about the source of her work. She playfully responded: ‘Nothing is taken from anything! Or anything from nothing?’ This riddle, imbued with paradoxical or possible nihilistic intent, exemplifies much of what she did. Whilst drawing on various artistic movements of her time, from European expressionism to pop art and narrative figuration, she continuously subverted their tropes, creating a unique aesthetic style imbued with humorous, erotic and violent vigour. A prolific artist with an astute eye until her final days, she found inspiration in the world around her, exploring themes ranging from popular culture to politics, continuously transforming her subject matter, like an alchemist, in a quest for constant reinvention.

Her artistic journey began at an early age, having been introduced through her art collector parents to some of the key circles of the post-war avant-garde. In 1958, De Jong worked at the Stedelijk Museum in the Applied Arts and Design department while studying art history at the University of Amsterdam. During this time she came into contact with members of the Situationist International (SI) – a group of artists, writers and social critics who aimed to disrupt capitalist systems. De Jong met Asger Jorn in 1959 in London with whom she would develop a personal and professional ten-year relationship, and then Guy Debord in 1960, when, among only a handful of other women, she officially joined the group and settled in Paris the following year.

De Jong left the SI in 1962 due to her support for its German fraction, Gruppe SPUR following their exclusion from the movement. Her short-lived involvement with the group became a defining aspect through which her life and work has been viewed, at times overshadowing her oeuvre as an artist. For this reason, she largely avoided discussing this period of her life, preferring to focus on her own artistic practice. Combined with the prevalent underrepresentation of women artists of her generation, it perhaps offers an explanation as to why the wider institutional recognition of her work occurred only in the last two decades, with the first institutional solo exhibition in her native country only taking place in 2019 at the Stedelijk Museum.

It was in the early 1960s that De Jong would start to define her artistic practice. She sought to explore the human condition against the backdrop of the rapid cultural shifts of the time, both in print – through the English-language publication she founded, ‘The Situationist Times’ (1962–67) – and in paint, using an array of styles from European expressionism (‘Accidental’, 1964–65 and ‘Suicidal’, 1964–65) to pop art (Pop, 1966–67 and Erotic, 1968) where hybrid monstrous figures engage in scenes of violent play and erotic delight. Following several changes in circumstances in Paris, including complications with her residence permit, she returned to Amsterdam in 1971, where she produced some of her most ambitious and eclectic work, including a series of diptychs, ‘Chroniques d'Amsterdam’ (1970–73), which combined two canvases into foldable wooden-framed suitcases, collapsing text and image into painted collages that intuited auto-fiction in art.

Later that decade, she embarked on two pivotal series of paintings: ‘Billiards’ (1976–78), centering on the popular eponymous bar game, and ‘Série Noire’ (1980–82), which explores the premise of post-war French crime novels as its subject matter. By revelling in the erotic and violent subtext of the modern underworld, these works allowed her to explore a more pictorial approach to painting, using bold colours and subtle brushwork, while also toying with the limits of artistic genres of the time such as narrative figuration. In the 1980s and ’90s her work expanded in scale. This growing interest in monumentality, upset by the creeping chimerical figures found in her earlier paintings, is seen in series such as ‘Upstairs-Downstairs’ (1984–88), comprising 27 works commissioned for the Amsterdam Town Hall; ‘Dramatic Landscapes’ (1984–85), a body of work which disrupts the tradition of landscape painting; and singular works like De achterkant van het bestaan (The backside of existence, 1992), a large painted sailcloth suspended in mid-air.

In recent years, De Jong turned much of her focus to the subject of war and human suffering, a recurring topic, which testifies to her political engagement which was present as early as the 1960s in her graphic works of the May 68 protests. This preoccupation with war was also no doubt impacted by her experiences of displacement as a child – fleeing Nazi-occupied Amsterdam with her mother in 1942 and living in exile in Switzerland until 1947. While she already grappled with themes of conflict in the 1990s in a series titled ‘Megalith (Gulf War)’, she would later dedicate entire bodies of work to the subject: from a series on World War I (‘WAR’, 2013–2014) to the rise in refugees and undocumented economic workers across Europe in ‘Border-Line’ (2020–2021) and several paintings from 2022–2023 dedicated to the invasion of Ukraine. Her final works, which I visited in her attic studio in Amsterdam and left untouched since her passing, focus on Gaza. One unfinished painting from this series still stands upright on its easel, its surface delineating a violent scene wrought with destroyed buildings and bloodied bodies.

In a video that Hans Ulrich Obrist recently resurfaced on Instagram, De Jong advises: ‘Don’t only look at yourself, look around’. Beyond the intricate and unique complexity of her multifaceted oeuvre, it was De Jong’s resolute ability to reflect her present time, with all its disquieting truths, that profoundly resonated with generations of us who were moved by her work. She forced us to question our relationship to the world and its status quos. In these tumultuous times, this is perhaps one of her greatest legacies.

Jacqueline de Jong's ‘Le Petit Mort’ is currently on view at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery until 16 August.