Zoë Buckman is a warrior of the physical. Throughout her life, she has moved through experiences that span from the banal to the unbearable. She is not afraid to confront, comment, and speak about the range of complexities that define her individual experience. Over the years, she has captured, taken notes, gathered, built, and threaded narratives of her life with an ongoing expansion of how she comments upon the multiplicity of her existence.

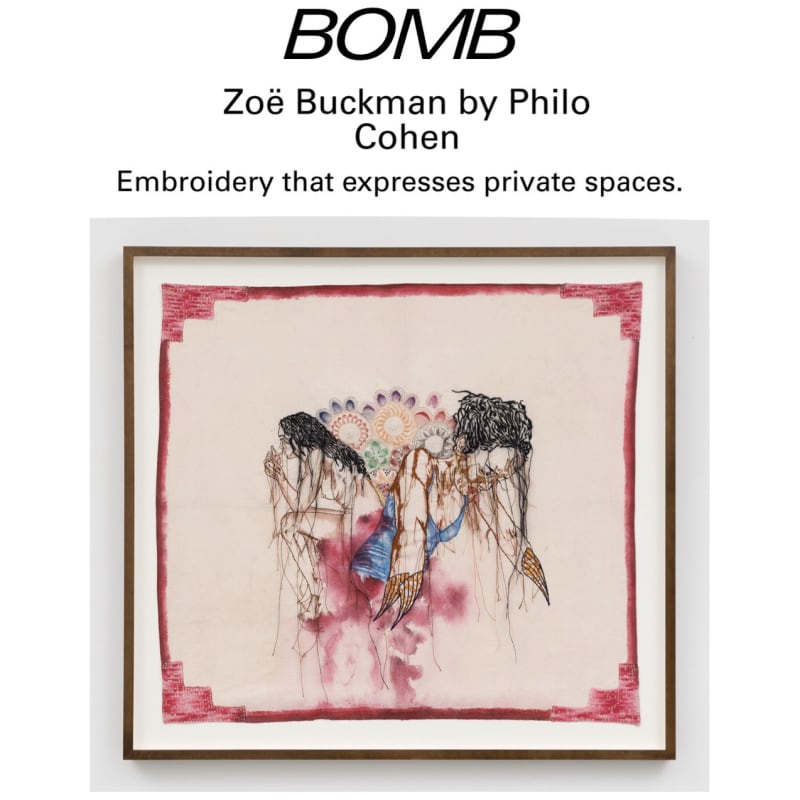

Buckman’s current solo exhibition, Tended, is on view at Lyles and King Gallery in New York City. In the work on display, Buckman covers vintage tablecloths and napkins with multicolored threads that she utilizes as a medium for her storytelling. Antique fabrics collected by Buckman are displayed like windows on the white walls of the gallery space. I like to think of these pieces as windows because they present viewers with both the joys and the hardships of the everyday. In the conversation that follows, we speak about embroidery as chosen craft, transgenerational kinship, Judaism, and the need for artists to speak, always.

—Philo Cohen

Philo Cohen Embroidery is traditionally perceived as a craft of the feminine. Can you give readers some context on how you came to embroider?

Zoë Buckman I took textiles back in school. I wasn’t particularly interested in embroidery, but I found it really easy. So I figured it was a class that I could coast through and I could get stoned in, putting in minimum effort and still pass. After that, I didn’t touch a needle and thread again for many years. I pursued photography as my more formal art education. While I was at the International Center of Photography, I realized that I wasn’t comfortable with photography and lens-based media. There was this separation between me, my ideas, and the finished piece. The fact that my work would be printed over here, spat out over there, or living on a hard drive—I hated that. While in school, I kept on trying to figure out how to marry my writing and things that I’d overheard with images I was making.

Years later, after I became a mother and started to expand my practice, I was working on a series called Present Life (2014–15). It was about death and mortality in conjunction with the maternal experience. It was an expansive time for me. I was exploring different mediums; I felt confident. I think the experience of giving birth and becoming a mother really put me in touch with both my power and my intuition. During that time, I was clearing out some of my late grandmother’s things, and I found a lace table runner and thought to myself that I had to do something with this object. I wanted to embroider text onto it.

Embroidery is very personal; it’s quiet; you can carry it with you wherever you go. Embroidery worked for me in that moment because I had just had my baby, and my time was very limited. In doing it, I felt instinctively that I was taking part in a kind of history of female expression. Over the years, I’ve just been really learning more and more about that and the importance of it.

PC Throughout the years, were you always writing?

ZB I grew up listening to hip-hop as my chosen genre of music. I would go to the battles and the open-mic sessions in the British hip-hop scene. I would also listen to a lot of American rap. I grew up in a working-class part of London where hip-hop was on the streets. At home, I was surrounded by literature because my mother was an acting teacher and writer. I was around Shakespeare, poetry, sonnets. My mother literally spent her life creating stories, and I was inspired by that. Writing came very naturally to me.

The majority of the text in the show at Lyles and King is from my writing. It’s a combination of a more journalistic style intertwined with some poetry I wrote when coming out of really difficult experiences throughout my life. For example, I had an abortion right after my mother died, and I had it alone because the man whose actions had put me in that situation decided that he wasn’t going to come to New York but instead stay in Canada where he was working. A lot of the writing in the show is from that specific experience, which was some years ago.

PC Can you speak a bit about your choice of scale, how your largest work is still human-sized, and any emphasis on the intimate in the sizing of your pieces?

ZB I have been edging up in my use of scale, and that has to do with me getting more confident in finding my footing with this new form of expression. For me, nothing is larger than life. I am trying to draw viewers in. I am speaking about a private space. In my work, there are writings that I’ve done privately, some text messages my mother has sent me, and images of real-life moments with me and my friends that I have captured. It doesn’t feel appropriate or sensitive to make work that is physically huge. I don’t want it to be garish. I don’t want it to provoke a gasp or awe. I want viewers to come close and have an intimate experience with the work, which is why things have tended to be pretty small.

PC Despite the strong degree of intentionality in your work, there is also a play around chance and the politics of letting go. I am intrigued by the open spaces in your embroideries. Can you speak on your relationship to what art historians love to call “negative space” and where you choose to thread, where you choose not to, and how you choose to leave space for our eye to decide?

ZB I think there needs to be ninety percent intention and ten percent chance. If we get too attentive about our choices, then we become perfectionists. I have seen creative people fail because of their own perfectionism. Ultimately, what is a perfectionist? It might come across as someone who is self-deprecating, claiming their work is never ready, never good enough. But really, it is all about their ego. They think that they can and should do something perfect. Once I recognized that only the divine can achieve perfection, and that I am not God, then I recognized that there was nothing I could ever do that would be perfect. So I might as well just give it my best shot and release it.

PCI saw you mentioned vanessa german’s practice as being inspirational to you. I find the connection between your work and german’s to be an interesting one because you both comment on the importance of feminism in the battle for restorative justice. Can you develop a bit about that kinship and what it is about german’s work that moves you?

ZB For me, vanessa german’s work is absolutely brave and powerful, but it also carries a deep softness. She is obviously really into found objects and pieces that have existed within functionality. She takes functional objects and assembles them into something completely different from their original intention. I absolutely love that. vanessa’s captions on Instagram are full-on poems. I can’t look at vanessa’s Instagram quickly! I won’t do it. I save it for later, when I have a cup of tea, because I know she is going to write something that is going to expand my heart. I’m really impressed by her, and I love her as a human.

PC Earlier this month, I helped organize a benefit event in support of Planned Parenthood and the criminal justice organization Galaxy Gives. The event called for collective action as a means to salvage bodily autonomy. Artists are important vectors for social change. They are critical actors in shaping dialogues and understanding the need for collective liberation. Can you speak a bit about your stance on the need for intersectional alliances as a means for radical change, and your thoughts on how art can contribute to that change?

ZB It’s interesting because when I make work I’m not thinking so much of the outcome, but rather I am thinking about how I want the viewer to feel. I’ve been making work about the experience of abortion for over ten years. In a way, I wish it hadn’t become more relevant. I wish that the work that I was making ten years ago with the uterus as a main subject was completely irrelevant now. In fact, I wish people saw it as vintage. I do share your hope that art can have the capacity to affect change. All creative disciplines together have the capacity to. I’m just frustrated that creators are not using their voice as much as I wish they would.

A perfect example of that is actually in the fight against anti-Semitism. As a Jewish person, I know one of the reasons why most Jewish people with a platform don’t usually comment on it is because one gets so much hate when they do, and they often get misunderstood. It is really hard and challenging all around. Speaking about anti-Semitism doesn’t feel good. It doesn’t make you popular at all, and it’s hard for people to get behind it. But at the same time, I feel that I owe my ancestors to provide positive representations of the diversity of Jewish life. In parallel to that, I also have a responsibility to my ancestors and even just to my mother to highlight the fact that anti-Semitism is rising globally.