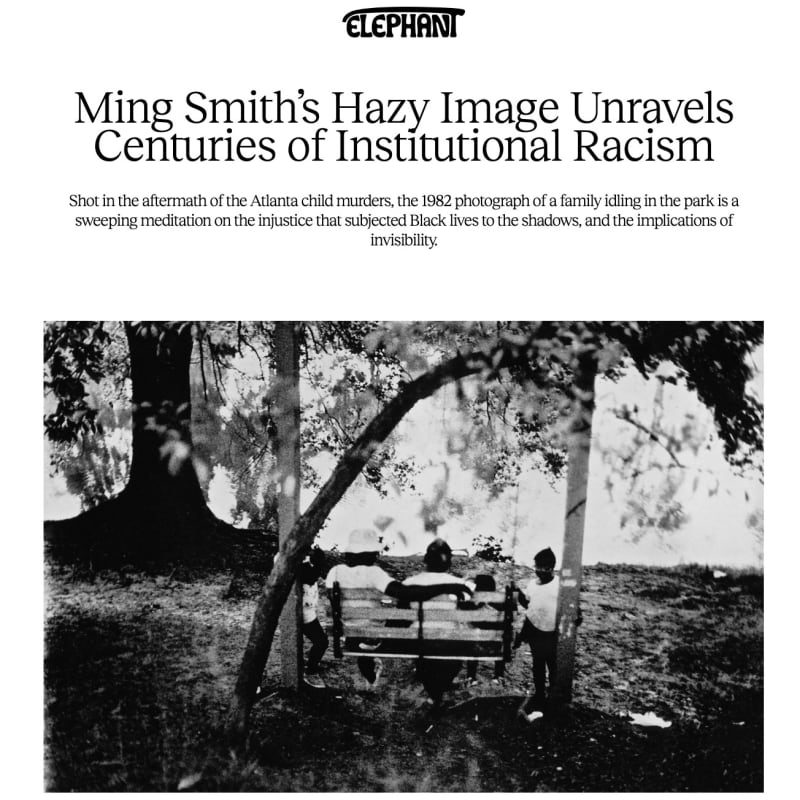

Piedmont Park, Atlanta, 1982. It was a sweltering summer’s day, and there was jazz playing. A Black family unwind beneath the foliage which offers shade. The parents recline on a bench; the children are nearby, under the watchful eye of their father, whose outstretched arm is a pledge of protection. Their bodies are pressed between the ethereal whites and the corporeal blacks, the sounds and the silences. Condensing these crashing contrasts through her characteristically slow shutter whilst on an afternoon wander, Ming Smith produced a photograph of fragile beauty—one that was inflected by the societal strains in Atlanta at the time.

The city was in mourning. At least two dozen Black children—most of whom were boys—had vanished. They were walking home, riding their bicycles or off to the grocery store, always in broad daylight. “It’s 10pm. Do you know where your children are?” sounded television sets, a daily warning that spoke very directly to Atlanta’s African-American community, who were terrorised by these disappearances between 1979 and 1981. Parents hovered over their children and forbade them from playing outside; some were pulled out of school. Most of the bodies were eventually found—behind dumpsters, under bridges or deep in the woods. Yet some were never found at all. The question ached from the city’s broken heart: “Who is killing our children?”

Furious at the lack of urgency and investigative rigour displayed by police officials—as exemplified by their refusal to follow leads which had implicated the Ku Klux Klan, of which members were included amongst police ranks at the time—grief-stricken mothers organised to make noise until someone listened. Psychics, bounty hunters and the red-bereted Guardian Angels marched into the streets, while President Reagan—in an effort to evidence the “colour-blindness” of his administration—deployed dozens of FBI agents to inject firepower in the city’s search for clues or suspects. Atlanta was turned inside and out—but to no avail.

“Grief-stricken mothers organised to make noise until someone listened"

Smith’s photograph, titled Family Free Time in the Park, was taken a few months after a young Black photographer named Wayne Williams had been sentenced to lifelong imprisonment. He was convicted for the killing of two adult men, which the police argued were linked to at least 23 of the murdered children. Inexplicably, all the cases were closed. To this day, Williams—who still proclaims his innocence—has never stood trial for these murders. No one has.

This judgement left many questions unanswered; the evidence presented against Williams was, undoubtedly, flimsy. In his searing 1985 book, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, James Baldwin echoed the scepticism that was felt by many of the victims’ families in the wake of the verdict. He posited that the belated efforts to solve these crimes were less about serving justice for the poor and Black, and were instead borne out of a desire to end the media scrutiny that the murders had attracted.

Watching the prosecution tie Williams’s supposed homosexuality to a spate of cases in which no sexual assaults occurred, as well as map out a “pattern” of murders where the causes of death varied widely, was, for Baldwin, reminiscent of a history of white people fearing Black men. He declared that Williams “must be added to the list of Atlanta’s slaughtered black children.” Just as devastating was Baldwin’s admission that he—as a gay, Black man himself—could have very well been the one serving time instead.

“Belated efforts to solves these crimes were borne out of a desire to end the media scrutiny that the murders had attracted”

Last year, Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms reopened the cases, with the hope that new DNA technology may be able to provide some form of long-awaited closure. After all, if the bodies of murdered Black children are not enough to launch an exhaustive, albeit late, investigation—let alone topple a corrupt criminal justice system—then how can Black lives ever matter? It is a question that has gathered a whole new gravitas for the people of Atlanta, who this June witnessed Rayshard Brooks’s fatal shooting at the hands of a white police officer. It was yet another violation exposing the institutionalised racism that has for centuries rendered Black Americans invisible—the same invisibility that threatens the Piedmont Park family, whose figures dissolve into an abstraction of lines, angles and deep shadows.

Though Smith’s photograph is very much embedded within the context of a city still coming to terms with an unspeakable tragedy, these blurry bodies are at the same time bound with their ancestors. For the ground they rest on is saturated by the trauma of the chattel slave trade, economic exploitation of Reconstruction, Massacre of 1906 and apartheid of Jim Crow. Transmitted from generation to generation, Atlanta’s Black people had yet to know a time free from the tyrannies of a state that had thrusted them to the brink of social erasure. As Baldwin wrote in his preface to The Evidence of Things Not Seen: “It never sleeps—that terror, which is not the terror of death (which cannot be imagined) but the terror of being destroyed.”