By Karen Wilkin

The Denver Art Museum’s “Women of Abstract Expressionism,” the first show to focus on the topic, was probably inevitable, given today’s hypersensitivity to matters of gender. But given the not-unfounded perception that the New York art world of the 1950s was dominated by hard-drinking, chest-beating males, who overshadowed and condescended to their female colleagues, it’s important to be reminded that women played a role in the era’s radical rethinking of aesthetic possibilities. So why did I emerge from a leisurely visit to the show with its passionately enthusiastic instigator Gwen F. Chanzit, curator of modern art at DAM and director of museum studies in art history at the University of Denver, feeling not exhilarated and excited, as I’d hoped to be, but mildly disappointed?

My expectations had been raised by the exhibition’s ambitious catalog, which includes essays by Ms. Chanzit and the art historians Robert Hobbs, Ellen G. Landau, Susan Landauer and Joan Marter (editor of the Woman’s Art Journal), plus an interview with the distinguished critic Irving Sandler, a friend to and welcome studio visitor for many of the exhibited artists. There’s a good chronology, informative documentary photographs, illustrations of most exhibited works, and brief biographies of 42 female painters—many obscure; most from the East Coast, some from the West; only one, Alma Thomas, African-American—each with one work reproduced. The criterion appears to have been that at some point in the 1950s, each of them made paintings that responded to Abstract Expressionist ideas; that several of them are known for quite other kinds of work does not seem to have been an issue. Not everything is particularly noteworthy (or particularly original), but it’s difficult to fault the desire to enrich the history of recent American art as written to date.

The exhibition is necessarily far more modest, concentrating on groups of work by 12 painters— Mary Abbott, Jay DeFeo, Elaine de Kooning, Perle Fine, Helen Frankenthaler, Sonia Gechtoff, Judith Godwin, Grace Hartigan, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Deborah Remington and Ethel Schwabacher. The Daniel Libeskind-designed wing of DAM, with its perverse slanted walls, has been improved by vertical insertions, but the resulting spaces are still cranky and somewhat incoherent. On the plus side, we get informative views of other artists’ work from each individual section.

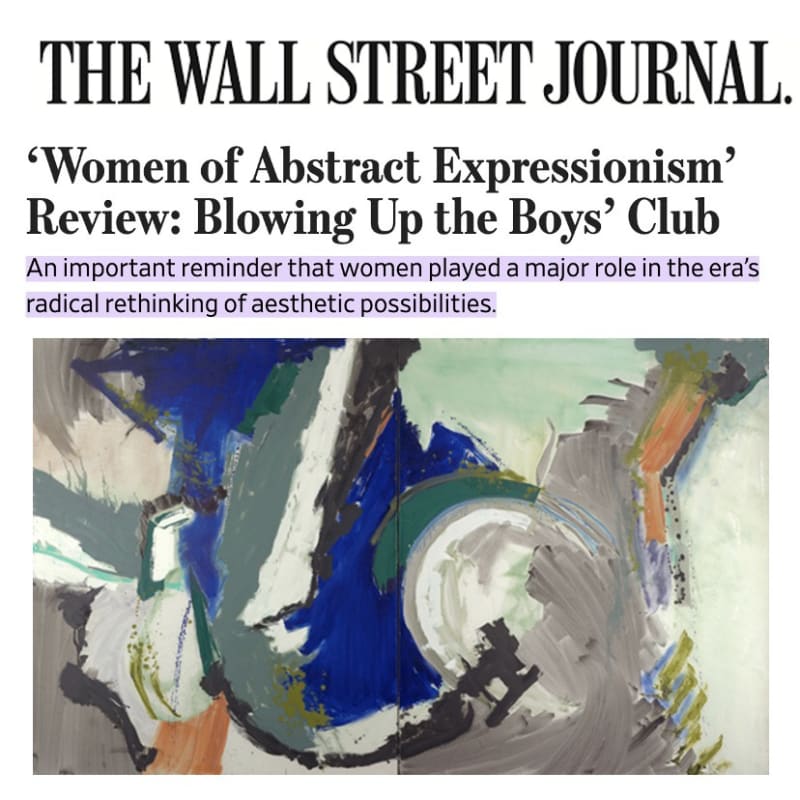

Also on the plus side, “Women of Abstract Expressionism” includes some first-rate paintings: “Abstraction,” a small, tough 1947 De Kooning, all vigorous strokes and high contrast; Frankenthaler’s radiant “Jacob’s Ladder” (1957), with its delicious greens and rusty pinks; Krasner’s bold “Stretched Yellow” (1955), an homage to Matisse, striking for clear color and emphatic collaged-on floating, dark shapes; Hartigan’s robust, deep-red, economically constructed interior, “The Creeks” (1957). The selection of Mitchells is exemplary, emphasizing the not-always-apparent variety with which she could compose her webs of paint.

These painters all shared their male colleagues’ convictions that the source of art was the unconscious and that the artist’s role was to reveal the unseen, not to depict the known. But were they Abstract Expressionists or even, in some instances, abstract painters? Frankenthaler rejected Ab Ex’s contingent, wet-into-wet gestures—which just about everyone else in “Women of Abstract Expressionism” embraced—inventing, instead, an influential method of staining with floods of thin, luminous color; De Kooning and Hartigan both worked largely with figurative imagery, albeit freely. (That Frankenthaler would have shunned any show that labeled her a “woman” anything is another matter. Like many others in the exhibition, she always insisted that she was a painter, without qualifiers.)

Surprises? For the most part, the selections remind us why the best known of the included artists are the best known. The less familiar Gechtoff’s murky, energetically scrawled canvases, done before she left San Francisco for New York, are unexpected, but those done afterward are fairly generic. Fine’s scribbled black-and-white canvases are extremely accomplished and clearly impassioned, but there’s a flavor of Philip Guston ’s drawings. It’s remarkable that DeFeo’s enormous, encrusted slab of matte gray oil paint, punctuated by dangling strings, is in the show—it resembles a rock face and probably is as easy to transport—but it posits ideas about materiality and physicality very different from those associated with Ab Ex.

The show raises provocative questions, such as “does women’s abstraction of the 1950s differ from men’s?” The curators suggest that women were more willing to allow references to specific experience into their work and cite titles as evidence, even though they were usually attached after the fact. Maybe. Frankenthaler’s “Jacob’s Ladder” was a response to the structure of the completed picture. An accompanying film, with clips of all 12 artists, provides interesting observations, contradictions and other ideas. The big question, of course, is why the 12 women included in the show were chosen, rather than any of the others in the catalog. We all have alternative lists. Mine is headed by Alma Thomas, not strictly an Abstract Expressionist, perhaps, but a hell of an abstract painter.