By Beth Williamson

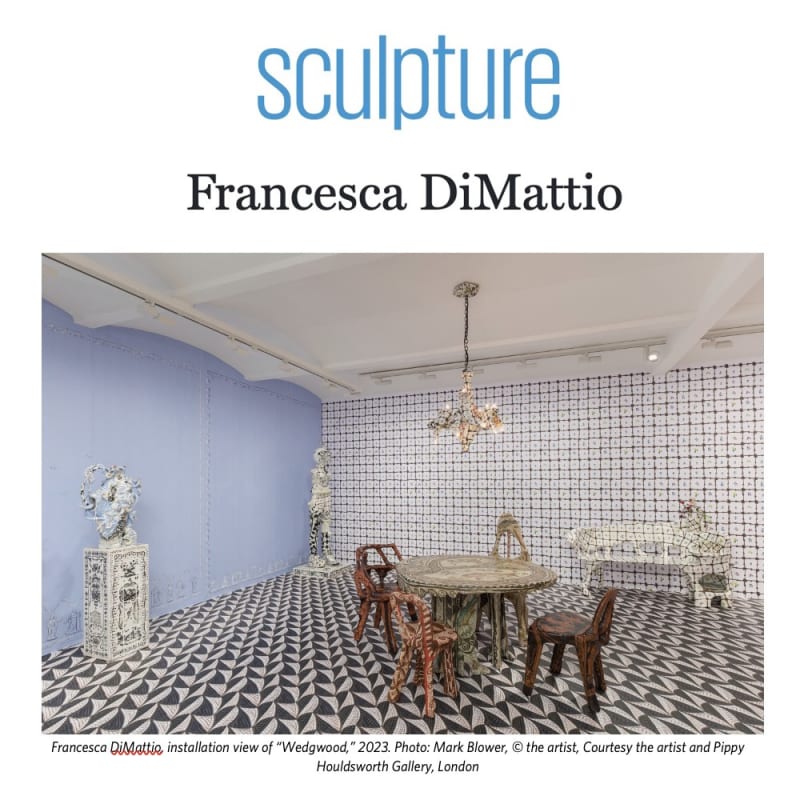

Walking into Francesca DiMattio’s “Wedgwood” (on view through December 23, 2023) is like entering an enchanted world; nothing is quite what it seems. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland immediately comes to mind—everything is just a little off-kilter, our perceptions just a little bit skewed. DiMattio’s immersive installation presents a domestic scene of sorts, but it’s not as cozy or pretty as it first appears. Patterns or textures or both cover every available surface, including three caryatid figures, clashing colors and shapes creating a disorienting cacophony—particularly in the flooring and wallpaper designs created by the artist.

Mosaic Table Set (2022) furnishes the center of the space, while additional seating, including a Sèvres Tableware Bench (2023) and a Pink Sèvres Chair (2023), is dotted around the room. From a distance, the furniture looks fragile, though it is not made from ceramic, as might be imagined, but from wood covered in paper pulp or clay, then sealed with clear coat automotive paint. Visitors are encouraged to sit on the seats, which offer comfortable perches from which to take in the details of the surrounding environment with its strange mix of styles and eras—grandma’s house meets contemporary eclectic. There are candle sconces, a mirror, a chandelier, and other decorative sculptures on plinths, as well as Sèvres-style crockery, including a charming cake stand and four delightful little cups.

DiMattio’s ceramic caryatids (in porcelain, stoneware, and terra cotta) occupy the space in various guises. Scuba Caryatid (2023) stands sheepishly in a corner wearing a mask and snorkel, and there is no doubt about what it’s been doing. The clothing draped around its shoulders and waist is reminiscent of crochet and coral, and there are Meissen floral clusters mixed in, too. Scuba‘s shorts match the Sèvres wallpaper, while mismatched footwear adds to the ensemble. Bauhaus Caryatid (2023) is a more confident figure in black and white, save for the terra-cotta “cardboard” package that cleverly serves as a pelvis (an Amazon box forms its head). The Bauhaus reference, as made clear by the figure’s t-shirt, is not to the German art school, but to the British band famous for “Bela Lugosi’s Dead,” recorded in 1979. Across the room, Wedgwood Caryatid (2023), a baby-blue sweetheart of a sculpture wearing briefs that appear to be knitted, is strewn with remnants of the sea—shells and seaweed drip down its childish body, some glistening as if still wet, morphing into Wedgwood decoration along the length of one leg, which has been replaced by a vase. A ceramic sports brand label adorns its chest, like an identification tag, while its mismatched feet and legs lend an unexpected vulnerability.

These figures carry a multitude of signs and symbols, slipping effortlessly between points of reference. Aside from the obvious Greek reference, the caryatids, despite their detail and ornament, also gesture, in some respects, to Eduardo Paolozzi’s collaged sculptures, especially from the 1950s, and Huma Bhabha’s much darker creations.

It is typical of DiMattio’s practice that her cultural references are so wide-ranging and, frankly, fascinating. There are French Sèvres porcelain and English Wedgwood jasperware designs from the 18th century, contemporary designs from fashion and sports brands, and Greek and Roman forms and decorative patterns. Such juxtapositions destabilize perception, forcing a reconsideration of what is valued artistically and, by extension, what human beings value in each other.