By Stephen Tayo

For an artist, finding the right medium is like entering a long-term relationship. The same tentative early forays, headlong tumbles into blissful togetherness, and reckonings with practical constraints make both experiences feel at once challenging and rewarding. If the bond is meant to last, there are always new revelations to be made—even after years together.

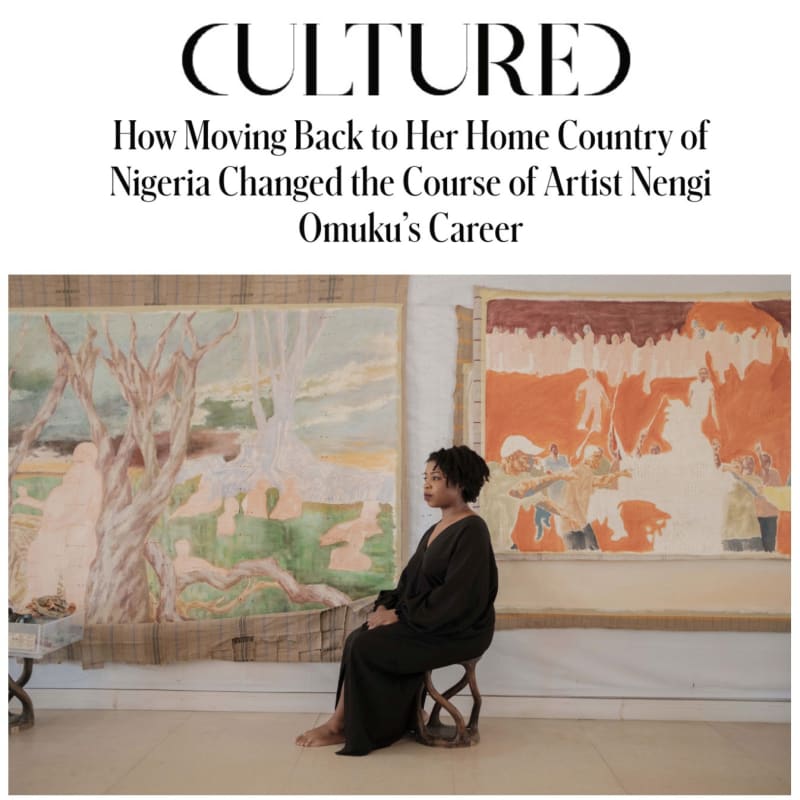

This is the experience that Nigerian painter Nengi Omuku has had with sanyan, a handwoven textile reminiscent of linen. Women traditionally use this cloth—a Nigerian symbol of prestige dating back to precolonial times—as head ties, skirts, and sashes for celebrations. Omuku discovered the artistic potential of the material after moving back to her native country in 2012, following six years at University College London’s Slade School of Fine Art. A decade later, her expressively textured oil-on-sanyan paintings have positioned her as a rising star in the Lagos art scene.

Textiles have long been a source of inspiration for the 36-year-old artist, who was raised in Port Harcourt by a florist mother and a geologist-turned-Anglican-bishop father. After returning home, Omuku entered a period of figurative painting, draping her subjects in fabrics. But the artist’s discovery of sanyan shifted the focus of her practice.

She took a year off from exhibiting in order to experiment with the material, learning how to layer paint onto it until it appeared “almost like a palimpsest.” Its earthy appearance also “change[d] my palette,” she explains, pushing her toward ethereal shades that lend a timeless quality to the work. Her source material ranges from live sitters, to local media photographs of protests and celebrations, to her own imagination.

The title speaks to a recent turn toward landscape in her practice. Eden is surrounded by scatter cushions, wooden stools, and locally sourced house plants, an installation first presented by Pippy Houldsworth Gallery at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2022. (At this year’s fair, Omuku’s work is being shown at both Pippy Houldsworth and Kasmin’s booths. She is also the subject of a solo exhibition, opening tomorrow, at Kristin Hjellegjerde’s Palm Beach location.)

The human impulse to seek solace in nature runs through the works on view at Hastings, all made between 2021 and 2023, as part of a “subconscious” response to the housebound anxiety of the pandemic. The Impressionists have been a powerful influence for Omuku, who points to the “liberating” impact of visiting Giverny, the home of Claude Monet, during a residency in France.

Another inspiration comes from closer to home: her mother, whose horticulture business she worked at for several years after returning to Nigeria. “I realized in preparing for the show that my first encounter with art was my mum’s colored pencil drawings of floral arrangements and landscape designs,” she says.

Coming home to Nigeria after art school marked a turning point in Omuku's practice—and not just because of her discovery of sanyan. She notes an essential shift in her thinking about questions of individual identity as they relate to the well-being of the collective.

In 2019, Omuku founded a nonprofit in Lagos called The Art of Healing, taking inspiration from the U.K. arts and mental health charity Hospital Rooms. The organization brings artists into the hospitals of Lagos, where they run art therapy workshops and paint collaborative murals. “It’s the most fulfilling part of my practice,” she says. “It’s one thing to express myself, but I feel like this is the true reason why I am painting.