By Major Jackson

In the early days of our long-distance courtship, just before Didi landed at Burlington International, often on the last, late-evening flight from Orlando, I would dash into Price Chopper for flowers. I’d run past blue-berries and navel oranges, past the guy restocking Keurig pods and teas, with the desperate look of a man fighting against the clock, the ceiling’s bright glare adding a sheen of drama to my quest.

Among the few remaining bunches fading in their cellophane cones, the roses struck me as too pedestrian. The white and pink lilies, the mauve orchids, or occasionally a handful of melodramatic tulips fainting in all directions seemed best for my purposes. I would pay and run out as fast as I came in.

The night clerks eventually caught on to my purchasing pattern; they took to grinning and joking about the prospects of a successful evening judging by what blooms I hastily purchased. This led me to seek out the self-checkout area.

Back at home, I’d have just minutes to curate a welcoming. A card, a fire in the hearth, Veuve Clicquot and two flutes. And from the china cabinet I’d grab a basic glass vase and commence arranging impatiens or freesia, whatever might convey sophistication and longing or, more importantly, prove that I wasn’t from the Paleolithic age. What began as an impulsive gesture of romance or mood setting eventually became habitual, expected even. Flowers in the vase, the crackling fire, a Vermont-themed sweet on the table. Not that Didi was the sort of woman easily seduced by such slavish and mundane shows of affection – what she admired more than the flowers was the consistent discipline, which conveyed stability.

Once, I shot into the store and, to my disbelief, discovered the floral department empty. Apparently, a delivery had been delayed by heavy snowstorms. Not wanting to break my streak, I grabbed a few carrots, a bunch of kale, and a head of red cabbage, and with some quick scissoring assembled the lot into a bouquet. Despite the spirit of whimsy, the arrangement failed to evoke flowers of any kind, just a container of uneaten vegetables.

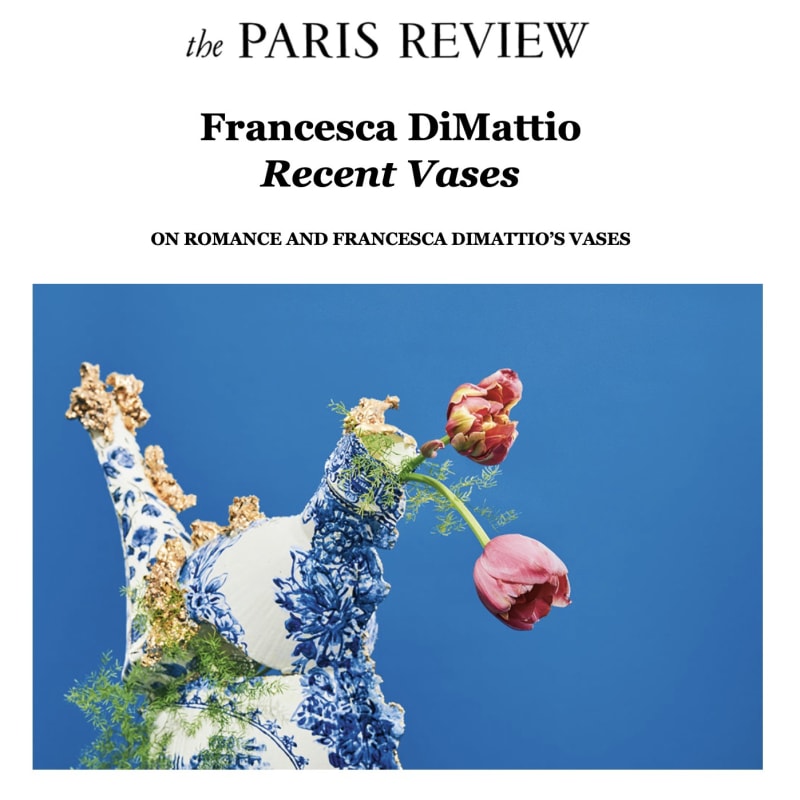

I would not have needed any flowers at all had I had one of Francesca DiMattio’s ceramic vases. Those assembled here, photographed by Robert Bredvad with an array of both exotic and familiar blooms, are functional in that they can hold and display flowers, but they defy that utilitarian purpose and the orthodoxy of the form, becoming exuberant sculptures, dynamic and organic unfoldings of the artist’s imagination.

A viewer of DiMattio’s work is likely to discover the frisson that arises from the distinct experience of having encountered something novel, innovative and strange. Merleau-Ponty’s assertion comes to mind:

It is by lending his body to the world that the artist changes the world

into paintings. To understand these transubstantiations we must go

back to the working, actual body – not the body as a chunk of space or

a bundle of functions but that body which is an intertwining of vision

and movement.

With these works, the fanciful spirit – the vision and movement - of her compositions is felt from all angles as a kind of intuitive collocation, the works of an intellect that has absorbed all manner of fine art and craft techniques, not to mention a storehouse of cultural references: chintz, Chinese pottery, African fetish dolls.

Take the fourth vase from the Boucherouite series, the title of which refers to the practice in North Africa of quilting rugs from recycled textiles and wool. Like the method that it seeks to honor, DiMattio’s blue-and-white sculpture, with its spirals, zigzagging lines, and fabric-like texture, fuses surprising elements over a traditional ceramic object. With this encrusting, the piece metamorphoses into a new specimen, an enigmatic creature. Another Boucherouite vase re-enacts a mythological scene in Wedgwood blue, even as it appears to be overtaken by a molten black substance. DiMattio’s visionary movements (both in subject matter and imagery) are startlingly swift; one minute the eye is roaming over the surface of a popular landscape scene on Chinese pottery, and then it is encountering floral details that give way to gold accents that seem to bubble up from the interior of the vase. DiMattio’s body of work naturalizes this velocity of association and irregularity and, indeed, makes a freedom of the asymmetrical displays, a whiplash of insinuations.

One might view DiMattio’s work as extravagant mutations, frozen in time. One might identify all their signification of culture and the history and function of porcelain wares in the home. One might even consider how one’s flowers would look against such a riot. However, taking my lead from Merleau-Ponty, I choose to contemplate how the primordial groundswell of DiMattio’s unconscious seems, through methods of combination and juxtaposition, to emerge as whimsical and boisterous forms, at once alienating and vivifying.

Flowers in the home are ultimately about ephemeral adornment and, quite possibly, forced titivation. One normally does not get lost in the sense of the inevitable or the strange. Fairfield Porter wrote once, “When you arrange, you fail.” What my flower-arranging routine lacked was the dreamlike wonder of DiMattio’s art and the freedom experience there.

What I did not fail at was persuading Didi, after a year of dating, to marry me. No flowers were involved when I proposed to her in my backyard that warm October night: luminaries spelled out will you marry me.

Now that we live together, not wanting to drop a routine that began as a courting ritual (who hasn’t felt the pain of that Barbra Streisand/Neil Diamond duet “You Don’t Bring Me Flowers”?), I have flowers delivered from a local florist on alternate Tuesdays. A box of mango-colored calla lilies one week. The next delivery: apple-green bells of Ireland mixed with orchids and staghorn fern.

Having encountered DiMattio’s work, I no longer ignore the vessel that holds the flowers. It heightens our appreciation of what’s contained and also, like Wallace Steven’s “jar in Tennessee,” presumes dominion and forces all around it to rise to its vital mysteries and strength of form. As with DiMattio’s Cartouche, there’s a casual interplay, a light conjugation, between the elements of the natural world and the vase shaped by human hands.

When the delivery arrives, we rush to open the box at the door. Often dizzy from the flowers’ perfumes, we admire their profusion, their ornateness. Even more, we are grateful for their colourful company and are reminded of our vows to surrender to what beauty we can muster. Where once I was ambivalent, we both take care to place them in vases that are as remarkable as their bouquets, a tendentious ceremony illustrative of our desire and aspiration. Both flowers and vase sit regal on our oak table, “tall and of a port in air.”