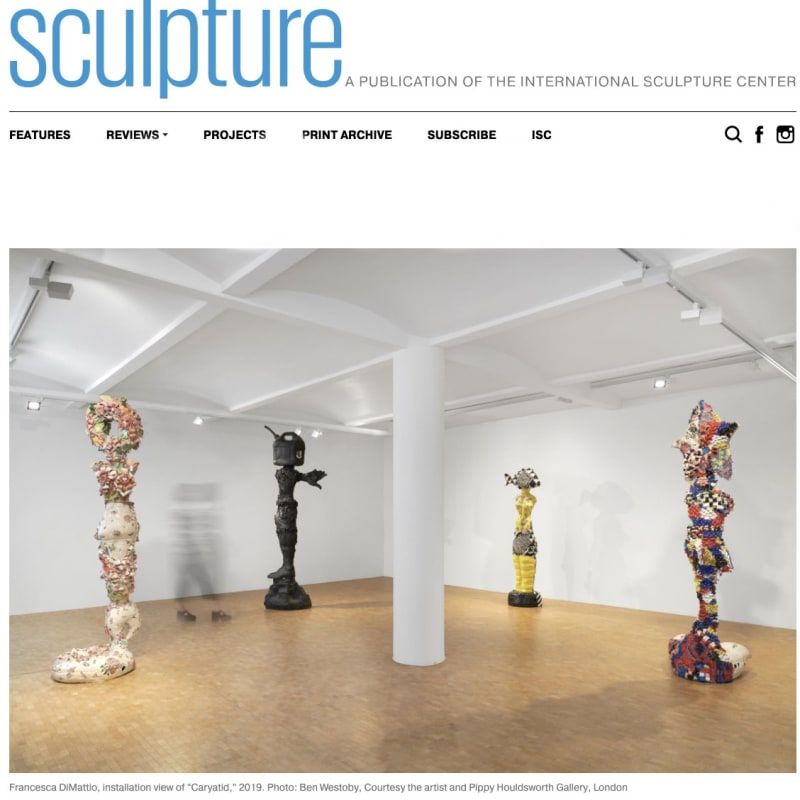

Four flamboyant, human-size female totems in porcelain confronted visitors to Francesca DiMattio’s recent exhibition “Caryatid.” Despite the show’s title, one was immediately struck by the fact that these figures had been liberated from their traditional role as architectural supports. While DiMattio calls her figures “Caryatids,” to my mind, they recall the towering female “archetype” sculptures of Liliane Lijn. Like Lijn’s mythical deities made from industrial, military, and household materials, DiMattio’s figures subvert traditional associations of femininity. Although their curvaceous physiques, inspired by store mannequins and classical statues, signal femaleness, other conventional signifiers of gender are teasingly muddled. In place of a head, one has a gas can, another a funeral wreath, a third a fish shape, and the fourth a star. Meanwhile their figures taper into surreally incongruous forms such as a tire or, in the case of Gas Can Caryatid, a single boot (adapted from a statue of George Washington).

DiMattio, who is based in New York, started out as a painter of monumental, boundary-pushing canvases that played with optical illusion and references to the history of art, design, and architecture. She translated this fluidity of approach to clay when she took up the medium in 2010. Rampaging through epochs and cultures, she borrows from whatever takes her fancy, with a refreshing disregard for conventional hierarchies. The Caryatid works (all 2019) exemplify this penchant for hybridity, each one encapsulating several oppositions—between masculine and feminine, playful and serious, contemporary and ancient, high culture and low. In Star Caryatid, DiMattio sculpted a star-shaped helium balloon for the head and jarringly juxtaposed it with a fragment of a Greek Venus. She shows similar irreverence in Flamingo Caryatid, pairing Meissen china and 18th-century Viennese porcelain with tight white jeans and a flamingo pool float for the figure’s base.

In addition to DiMattio’s unusual combinations, one marvels at the sheer technical feat of transforming feather-light objects such as a pool float or a balloon into solid porcelain. The various textures in these works demonstrate an extraordinary dexterity and inventiveness with her material. Each figure is adorned with elaborate decorations, from cascading ribbons and bows to chunky knitwear and boucherouite rag rugs, all vying with smooth, genteel glazes. The surface of Fish Caryatid, for instance, alternates between a yellow floral glaze and rough black and white basket weaving. If these tactile textures honor ancient women’s crafts, they also, on occasion, threaten to engulf the figures like an unruly, potentially sinister weed.

“Caryatid” also included four vases that fuse older forms and glazes with mundane contemporary items to comic effect. Spotting these pop culture intrusions is part of the fun of DiMattio’s work, and it often requires some scrutiny. Gnome consists of a misshapen turquoise vase whose bulging form on closer inspection reveals a half-hidden garden gnome. Nike I takes its name from the trainer propped jauntily against the base of a lurid yellow pitcher, serving as the lower part of its handle; a Sèvres peacock glaze spreads across vessel and shoe. In Ugg Buddha, an Ugg boot perches clumsily on the flank of a Ming Dynasty–style vase, which itself rests atop a Buddha, all glazed in the same white and blue design. Woven textures invisible from the fronts of the vases (as they were installed) tempted viewers to gain a full in-the-round perspective.

DiMattio has developed an invigorating language that enlivens and challenges ceramic traditions. The riotous clash of styles and eras gives an impression of continual evolution. Viewing her work, there is the sense that with one’s back turned, the gnome might burst forth from the vase or a caryatid glide across the room. Such is the bewitching world that DiMattio has created in clay.