First up is “Projects,” which opened February 4 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This deep dive into Smith’s black-and-white archives is a full-circle achievement: In 1975, she was the first African American female photographer to have her work acquired by MoMA. (Smith was also the first female member of groundbreaking photo collective Kamoinge, spotlighted in 2020 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.) At Frieze L.A., Smith’s “The Things She Knows”—new and rare choreographic-inspired works—will be on display at Nicola Vassell Gallery’s booth from February 16 through 19. “Feeling the Future,” opening in May at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, is a vivid counterbalance with splashes of color.

The aforementioned collaboration, titled “The Goddess,” is a partnership between Cadillac and Artnet, and will be unveiled later this month on Artnet Auctions. Ming, along with Petra Collins and Dannielle Bowman, was tasked with re-envisioning the Cadillac goddess ornament for their ultra-luxury EV CELESTIQ.

It’s a fascinating possibility, as Smith’s evolving, hard-to-quantify vision is decidedly uncommercial—and proudly so. Although she’s shot such icons such as Nina Simone, Grace Jones, Sun Ra, and Tina Turner, Smith is the great equalizer, humanizing her subjects even if they’re on stage. With an expressionist’s eye, she wields shadows as potently as light. She explores the Black experience, but taps into the universal, the abstract, and the other-dimensional. Her images resonate not just because of what they capture, but what they don’t. The narrative is often inscrutable; a through-line in her work is mystique.

“I always thought a photograph doesn’t need words,” Smith said. “I express what I need to fully in my photograph. It’s a complete thought, and the viewer can get whatever they want from it.”

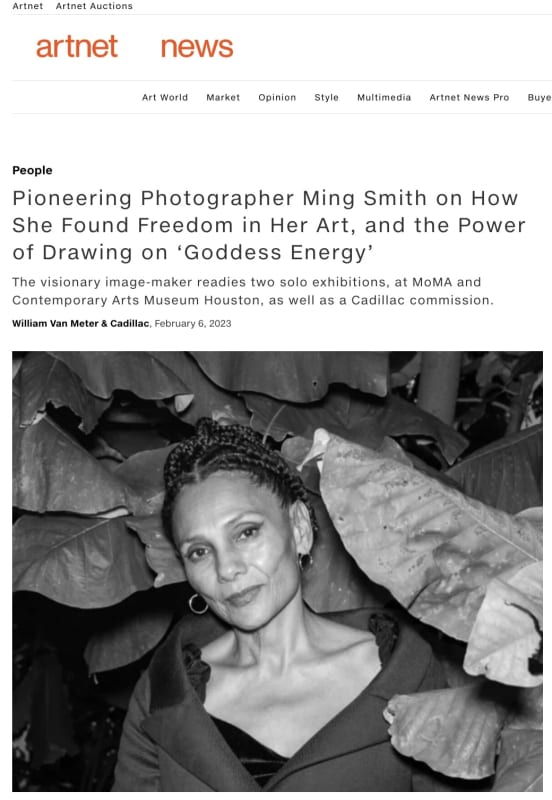

Smith sat down with us last month in her Harlem apartment. She was beatific in an emerald pleated skirt and cardigan, and looked decades younger than her 73 years. As she answered questions, she spoke calmly and moved and gestured with a dancer’s grace.

Let’s go back a few decades. You studied microbiology at Howard University. How does this connect to photography?

I was pre-med. I wanted to help people. My grandfather used to put me on his lap and say, “You’re gonna be a doctor.” I was trying to please him because it was his dream. My father was more of an artist. At Howard I had to take zoology, and we had to cut a frog. I was horrified—I just couldn’t. So I switched to microbiology, and I’m just now remembering this about studying chemistry: things were symmetrical. When you looked under the microscope, there was a lot of beauty.

I took botany and genetics. There was balance, form, symmetry, and beauty. It was very poetic, looking at the way things were made. I wasn’t thinking about being an artist then at all, although I photographed all the time.

I took an elective photography course, and the instructor—well, I shouldn’t say this, but he wasn’t very sophisticated or worldly. I asked him, “Can I have a career as a photographer?” He told me I could do medical photography. That’s better than when I was graduating from high school and my school counselor told me I could be a domestic, and why was I going to college?

Does this experience connect to why you went to a historically Black university?

Exactly. They were very, I guess you’d say, racist. There were a lot of teachers that were like that, but there were also a lot who weren’t. I remember my third-grade teacher, Mrs. Booth, showed us how to dance the Irish jig. She taught us watercolors. She had us singing. I realize now she introduced us to the arts. She was an older lady, and I remember one day she fell. And this guy that always liked me, I couldn’t stand him because he laughed at her. I was mad. I never spoke to that guy again.

You started taking photographs long before you were a photographer.

My father was an avid photographer; he had the Argus C3 and my mother had a Brownie that just stayed in the coat closet. I brought my mother’s Brownie to school when I was five and I took pictures of my first day of kindergarten. My mother was always like, “When are you gonna make you some money? You still doing that damn photography, that art?”

My father wanted to be an artist, but my grandmother told him that he could never support his family being an artist. And he could have gone to medical school, too, but he chose to be a pharmacist and have his family and do art at home.

Before becoming a photographer you were a successful fashion model. How was it being on the other side of the lens?

I was friendly, and I left—what else was there? I didn’t hang around. That was work. In the modeling world, I didn’t really fit in. Someone was always judging you. I was kind of the outsider, and I tend to have friends that are outsiders too.

The majority of the few friends that I had I met getting my hair done. I met Grace Jones and we bonded over girl talk. She was down. No one liked her. She was too much for this business. And I didn’t fit in. We became real friends and could speak the heart and exchange female energy. When she came back from Paris, she was performing at Studio 54. I didn’t go to Studio 54—I didn’t have the money! She says, “Bring your camera and I’ll leave your name at the door.”

You mentioned supporting yourself through art. But you never went the commercial route, even though you were coming from the fashion realm. You never looked at photography as a way to make a buck.

When I had any free time, I would go to the film houses where they had black-and-white films. I still plan to do a film one day, a beautiful film. I was really a loner. And I could continue to be so with my photography. I was doing street photography, in a way, at Howard, but didn’t know it. I could see a photograph and I didn’t need to be validated by what someone else said. It was coming from my own truth and I didn’t wanna mess with that, because this is where I had real freedom. I didn’t care what any critic said. For commercial work, you needed money to have a studio. You needed equipment.

Anytime I needed it, photography was a place to go to. As I look at it now, it was healing. This is what I hope: that people see my work one day and heal—or, you know, get involved in that instead of drinking or drugs or something. It was a go-to place where you could be private and no one could criticize you or tell you what to do.

You mentioned earlier that you appreciated the beauty and symmetry of microbiology. Your work seems decidedly asymmetrical, incorporating weird framing, imperfection, and an off-center point-of-view—qualities that make it special.

I think that’s part of being anti-establishment, my own way of protesting against things that are conventional and “the way it should be done.” You can create outside of that and make something really beautiful.

You were born in Detroit, Michigan, the car capital. Did that give this Cadillac project more resonance for you?

In the Black community, Cadillac is a status symbol. The Cadillac was always a signal of having arrived in life. My aunts and a lot of my family members in Detroit, they all had Cadillacs. They were entrepreneurs. They owned a pharmacy in Detroit. I have a series built on [playwright] August Wilson, it’s called “August Moon.” And one of my photos was of a Cadillac, because it was part of the folklore of the Hill District for me.

The theme for the Cadillac project was a reinterpretation of their “Goddess” hood ornament. It adorned most models from 1930 to 1956 and is returning on their ultra-luxury EV CELESTIQ. You found inspiration for yours in mythology?

Ma’at is a deity from ancient Egypt who stands for truth, justice, righteousness, and balance. There are 42 principles of Ma’at, almost like commandments—I shall not do this, I shouldn’t do that. She represents complete balance in that civilization. I was thinking about electric cars and all of this super high technology that’s going on. Maybe we’re moving too fast?

How was it working on this project?

This is one of the best shoots that I’ve had. I was really in my element and I just got some of the goddess energy from the statue. It was a very spiritual time. I worked over Christmas, the spiritual time for many religions. So, it was a very relaxed and spiritual process. I make my best work when I’m in a spiritual or meditative state.