The artist reflects on her storied career amid the launch of a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Ever since she arrived in New York from Detroit in the early 1970s, Ming Smith says, she’s led an aesthetically rich, if not always financially secure, life. “There was no way to support yourself as an artist back then,” recalls the photographer. “I did it for the love, for the legacy; it was what my life stood for.”

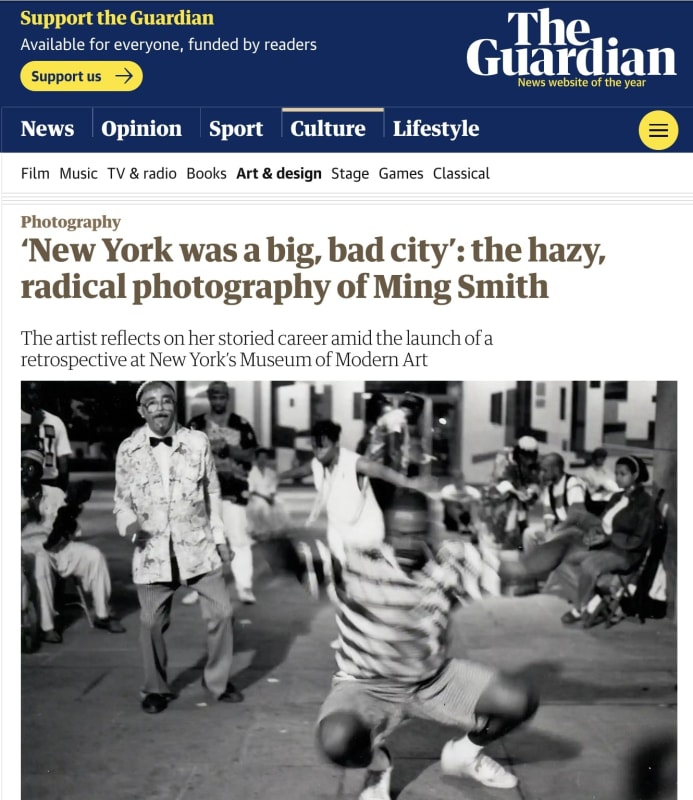

This month, visitors to the Museum of Modern Art in New York will be able to see a little of that legacy. The new exhibition, Projects: Ming Smith, goes deep into Smith’s archive to draw together images of seminal jazz musicians, such as Pharoah Sanders and Sun Ra, alongside quasi-documentary images of important sites of Black culture, such as New York’s African Burial Ground, as well as more fluid, impressionistic works, including her August Wilson series, a tribute to the playwright. All these images blur, both figuratively and literally (Smith favours hazy, long exposures), into a body of work in which it’s hard to distinguish the artist behind the camera

from the surrounding culture.

For the exhibition, staged in conjunction with the Studio Museum in Harlem, Smith worked with Thelma Golden, its director and chief curator, and Oluremi “Remi” C Onabanjo, from MoMA’s photography department, to select the pictures, many of which are going on display publicly for the first time.

Smith recalls feeling vulnerable as Golden and Onabanjo dug through two separate storage spaces, as well as the photographer’s current studio, to choose works, but she’s very pleased with the selection. “I think the editing was just brilliant,” she says. “You could take one image and it would introduce you to a whole mindset in the African American culture.”

Today, collectors, art-fair patrons and gallery-goers around the world know and admire Smith’s radical, evocative, black-and-white prints; the hip-hop producer Swizz Beats and the late fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld are just two of the prominent figures who have publicly praised her work. However, Smith’s route to success was long and varied.

Born in Detroit (her father chose Ming’s first name because of his love of Chinese culture) and raised in Columbus, Ohio, Smith studied at Howard University in Washington DC with the intention of becoming a doctor, before her squeamishness made her change her plans.

“I couldn’t cut the frog,” she recalls of her early dissection classes, “and just the thought of having to cut someone’s head open, and having the confidence to operate on someone’s brain, was awful! I didn’t even like to clean fish.”

Arriving in New York in the early 1970s, she started modelling, earning $100 an hour, more money than her father – a pharmacy graduate of Ohio State – was making in a week back home. “I didn’t care that New York was a big, bad city,” she remembers.” I knew who I was, and $100 an hour? That was my main focus.” Smith already had some camera skills, and, in visiting photographers’ studios, she gained greater insight into the form. She joined the Black photography collective the Kamoinge Workshop in 1972, then at the vanguard of the Black Arts movement (a kind of cultural counterpart to the Black Power movement), and developed a distinctive style and cultural focus. “That was the mindset with Kamoinge, to have our own personal take on Black culture,” she explains. “In Harlem there were painters, there were writers, but the world knew Harlem as a place of drug addicts, and poverty and children in dirty, torn clothes.”

Smith also worked as a dancer, which, combined with her modelling career, provided her access behind the velvet rope . In 1977, Grace Jones, the model turned singer, invited Smith to photograph her performance at Studio 54. The pair had first met at a notable hair salon, Cinandre, and hit it off.

“I went to get my hair done. She was a model, I was a model,” says Smith. “She was telling me her woes. We were women expressing our fears, doubts and our discontent about being a Black model.”

In 1978, a friend who was considering dancing for the jazz musician Sun Ra accompanied Smith to one of his concerts, where the photographer shot the band leader. “I got a call from this dancer friend. She was doing some kind of Egyptian dancing, and she invited me to the concert, so I took my camera,” she recalls. “That’s one of my most iconic photographs.”And in 1984, an invitation to appear in Tina Turner’s video for What’s Love Got to Do With It? led to Smith photographing Turner at the peak of her career.

Despite these encounters, Smith earned little from her photography for much of her working life. That changed about six years ago. In 2017, many museum visitors in the UK and the US enjoyed her work as part of the internationally acclaimed travelling exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power; following this show, Smith’s photographs were the subject of many commercial gallery solo exhibitions on both sides of the Atlantic, and she received plaudits in London and New York from the Frieze Art Fair. Later this month, a series of rare and never-before-seen works by Smith can be seen at Frieze Los Angeles in The Things She Knows. Next month, New York’s International Center for Photography will add to these accolades, when it bestows its annual lifetime achievement award on the photographer.

Though she is pleased to have received such praise, Smith says the work itself has always been her true reward. “It wasn’t necessarily having an exhibition or selling print, it’s the doing of it, that’s where the beauty of it, the joy comes from,” she says. “You can have some power; it’s not about beautiful clothes or the biggest house. It’s a lifestyle, it’s a mindset, it’s something about spirit.”

With this exhibition, she hopes to pass some of that spirit on to MoMA’s visitors. “The love of Black culture, that’s what’s important to me. Someone could see an image of [the acclaimed dance troupe] the Dunham Dancers, and it could open up a whole world; they could see a picture of [the jazz musicians] Randy Weston or Pharoah Sanders, and that could inspire them; they could see an image of the African burial grounds or August Wilson, and that could inspire them. It would be this wonderful, beautiful world that would open up to them.”