I once bled on the sheets of a man I hardly knew. Because he was put out, and I was ashamed - and for spite - I ordered a set of replacement sheets that cost half my monthly rent and had it delivered to his home.

There's an intimacy between our linens and our blood - and the sources of wounding or shame. Zoë Buckman's exhibition Heavy Rag at Fort Gansevoort features vintage tea towels embroidered with text that reads like confessional poetry. One, stitched with black thread on a crisp white background, channels the voice of the guy I once dated: "His eyes narrowed before, 'no Tampax or nothing, yeah? Just gonna bleed on my sheets and get back in?'" Another signals bravado in the presence of pain: "I told him I could get blood out of anything." In the press release, Buckman describes this body of work, which includes sculptural assemblages and ceramics, as representing the intergenerational experiences of women: "the exhibition embraces the domestic archetype by balancing an ambiguity between vulnerability and strength."

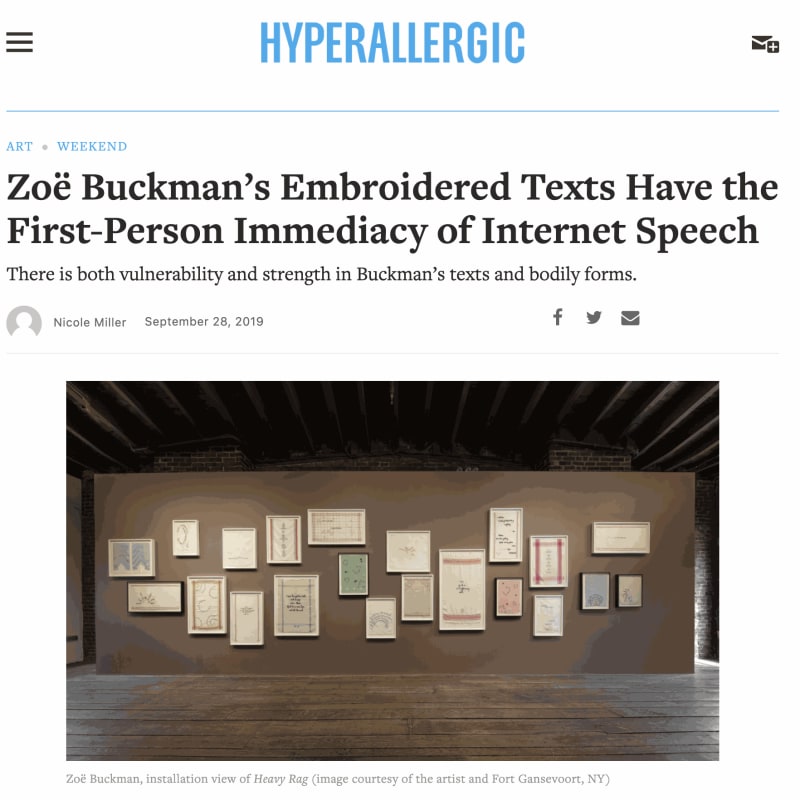

The artworks look great in Fort Gansevoort, a three-story 19th-century row house that feels like a domestic space. The framed embroideries hang on the first and third floors, near handmade porcelain cups, gauged and listing, that line shelves resembling mantles. On the second floor, boxing gloves covered with plaid or floral-patterned tea towels hang from the rafters in clusters or pairs that grip one another, perhaps in combat or mutual aid. Buckman points to Louise Bourgeois as one of her "spiritual mothers"; indeed, these bodily forms, suspended from chains, reference Bourgeois's hanging sculptures, while Buckman's framed embroideries borrow the compositional form of Bourgeois's lithographs on hand towels and other fabrics.

Heavy Rag recalls work by a second-wave generation of artists, such as Bourgeois or Judy Chicago, working with "domestic" subject matter or in mediums traditionally feminized and therefore marginalized. But Buckman's work is also indebted to the vocabularies of print and social media, where commodity consumption and pop-feminism converge. On Instagram, textiles and ceramics are not only the discarded materials of feminized domesticity, but also belong to the profitable image space of lifestyle branding. In the pages of glossy magazines like Harper's Bazaar - which recently featured Buckman and her work in a boxing gym alongside Victoria's Secret models who "champion women's rights" - tropes of feminine beauty and female empowerment merge seamlessly with the demands of the market.

First-person narratives have played a vital role in feminist discourse, including 1970s consciousness-raising and more recent forms of expression online. Within online space, the personal narrative has a new valence, as the obligation to use one's voice meets the business of monetizing one's image. Buckman's work reflects this imperative to mobilize both our speech and our image. Her embroidered texts - pithy statements delivered with no context - have the first-person immediacy of internet speech. Some, such as the phrase "It stings," (which the artist repurposed from a play written by her mother), have the rhetorical force of a hashtag.

The voices present in Heavy Rag echo recent efforts by women to make visible male supremacy. However, conversations and stories of male aggression circulated online often center on the vulnerability of women. As New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino points out in her new book, Trick Mirror, hashtags like #YesAllWomen and #MeToo "have made feminist solidarity and shared vulnerability seem inextricable, as if we were incapable of building solidarity around anything else."

This theme emerged at the exhibition preview, when I spoke with the artist and two other women. We wondered why the work of collective care is so often shouldered by women-why our fathers and husbands and brothers seem so bad at empathy. "Think about vulnerability," one woman suggested, pointing out that we've all likely had to ask a stranger for a tampon. "All of us can share that!" she said. "Every woman in the world."

Of course, for many women - including those who are post-menopausal or trans - bleeding is not the primary feature of being a woman. By centering the experience of one kind of woman - or rather, one aspect of women's experience - it's possible to build social solidarity; but political solidarity, which requires an attention to difference, may remain elusive. I wonder whether the artist's aims for the work - articulating not only the vulnerability but also the resilience of women - may be overshadowed by a conversation that seeks quick consensus about what it feels like to be a woman. "What we have in common is obviously essential," writes Tolentino, "but it's the differences between women's stories - the factors that allow some to survive, and force others under - that illuminate the vectors that lead to a better world."