When Art in America asked me last summer to serve as guest editor for this New Talent issue, I took the opportunity to realize a decade-old fantasy: to make an art magazine along with other Black writers and critics. My dream publication would focus primarily on new Black voices across the globe, and critically engage the concerns and ideas of artists, curators, educators, gallerists, and other cultural workers from academic and nonacademic perspectives. It would be a rigorous, accessible magazine: one that brought together the views of the many different audiences that encounter art, not just the white one that is most often prioritized. I have tried to bring that vision to life in the pages of A.i.A., using the space here to show that many kinds of art criticism are possible and, in fact, already exist, mostly in comments sections of social media posts, DMs, group chats, and—as Jeremy O. Harris, Jonathan Lyndon Chase, and Esteban Jefferson all suggest in these pages—among the gallery and museum ushers and security guards who spend all day with the work.

It is a problem that Black voices have been largely left out of art criticism, and that today’s arts coverage is dominated by a group of critics who are mostly white and non-Black people of color. The most celebrated Black art writers tend to be academics, which creates the impression that Black writers, unlike their white and non-Black POC counterparts, need a PhD to contribute to the discourse. In recent years, we have had all kinds of reckonings across the worlds of culture. And yet the gatekeepers of art criticism appear to have done little reflecting: the art critics who enjoy the security of salaries and staff positions remain almost entirely white.

These white and non-Black POC writers have started discussing “overlooked” Black artists and cultural figures. I ask, “overlooked” by whom? For decades, we’ve been reading the same few white critics, who hold coveted editorial posts at widely read outlets, and few if any have publicly acknowledged their own acts of erasure. Their articles about Blackness have contributed to a hyper-focus on Black art that deals with social issues alone; prioritizing this genre above all else continues that legacy of overlooking. Art and the audiences who see it increasingly reflect the larger culture, and we need to ensure that art’s written record represents many viewpoints.

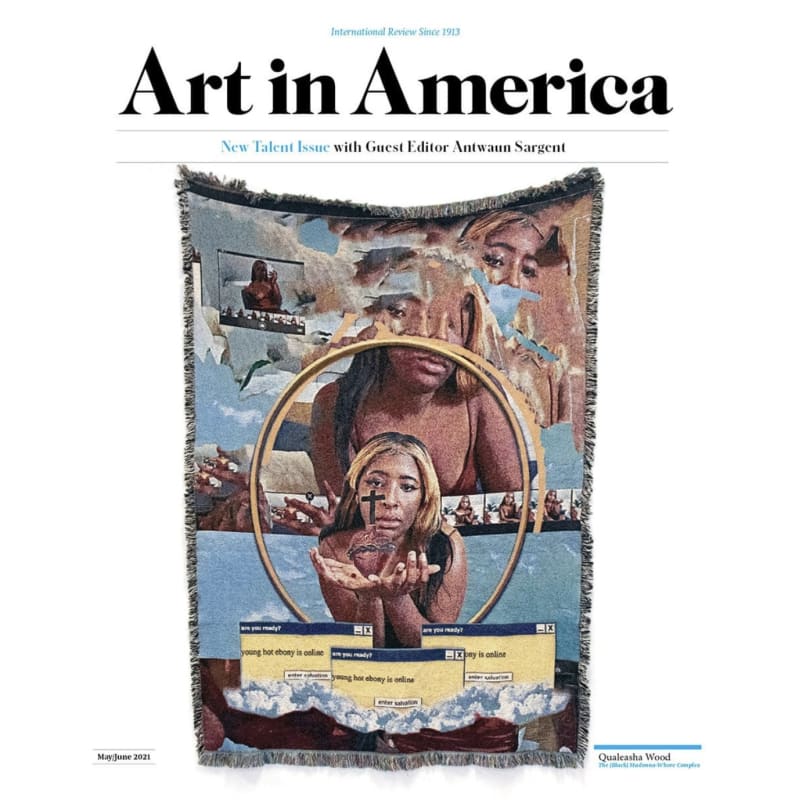

For this issue, I invited an international mix of Black writers, critics, curators, and artists—Jasmine Sanders, Nkgopoleng Moloi, Alexandra Bell, Jessica Lynne, Jordan Carter, Janicza Bravo, Emmanuel Iduma, and Connor Garel, among many others—to share their incisive perspectives on new art, which doesn’t necessarily mean young artists. I’ve read these writers over the past several years, at times agreeing and at times disagreeing with their work, all the while appreciating the fact that they were making it in a contemporary art mediascape that rarely values their voices. The issue also includes some artists I consider exciting new talent—Qualeasha Wood, Justin Allen, Miles Greenberg, and Tourmaline—whom I invited to take over a page of the magazine. The Brooklyn-based artist Cameron Welch has created a new pullout print for the issue: his Excavator mosaic speaks to histories of craft and mythology. Elsewhere, the painter Amy Sherald and photographer Tyler Mitchell engage in a rich dialogue about constructing a new American image. The robust and diverse range of approaches in this issue make me even more excited about the future of art.