Nengi Omuku skilfully captures the precarious atmosphere of 2020 in a vintage textile from Nigeria. But it is not all gloom.

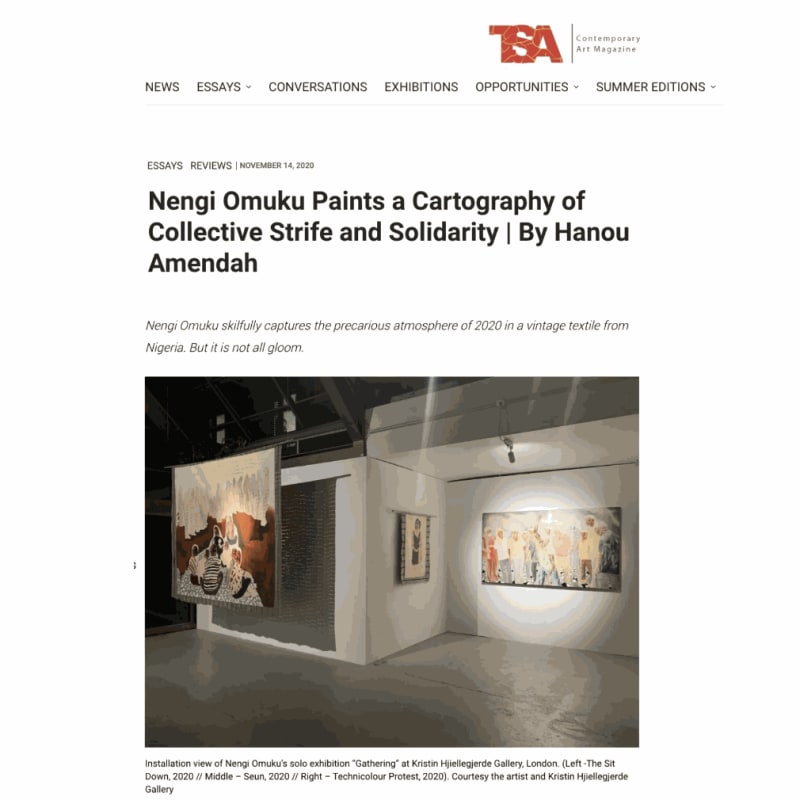

Light flooded through the glass ceilings on the upper floor of Kristin Hjiellegjerde Gallery in London. It continued its journey refracting into tiny rays of sunlight, which filtered through the small holes of the vintage Nigerian fabric Nengi Omuku used to replace canvas in her latest paintings. The exhibition bathed in a luminous atmosphere that sharply contrasted with the mood of the twelve paintings it encompassed, most of which examined the conflagrations of numerous social crises in Lagos, Nigeria.

The exhibition’s title, “Gathering”, can be slightly misleading as it evokes joyous celebrations and happy memories. At least, that was the spirit of “And co”, a rectangular piece featuring a wedding celebration. Although the bride and groom were the reason this joyous crowd congregated, they were not the centre of attention in the painting. From their peripheral position in the lower right corner, the couple locked in a tender embrace left most of the pictorial plane to be animated by their happy guests sporting matching green outfits. These seemingly supporting characters basking in the couple’s joy were in effect the artwork’s main subjects.

The joyous outlook of the painting was deliberate. On the day of the preview, narrowly brought forward to accommodate a single day of public viewing before a second national lockdown took effect in the UK, Omuku explained: “After […] everything this year has been, I wanted a painting that looked forward as opposed to reflecting. It is mostly about love.” The cheerful painting was somewhat the touch of hope, the light at the end of a tunnel of social and economic misery deftly rendered through a blend of astute composition and the recurrent use of a neutral palette of colours.

By contrast, “The Sit Down”, one of the most remarkable works in the exhibition, was filled with palpable tension. A small group of people with hunched shoulders and backs turned away from the viewers sat on a triangular-shaped surface. They faced a standing line up of ghost-looking antagonists. A red sea of anger and recriminations kept the two groups apart. The painting depicted a fictional scene inspired by the protests, which motorcycle drivers organised when the Nigerian government banned the use of two-wheelers and tricycles as taxis. With no real transitional measures in place, removing the affordable and popular mode of transport left thousands of young drivers jobless and urban dwellers stranded. Pathos in the exhibition reached its apex with “Gathering,” a harrowing scene of mourning. A crowd of non-identifiable people, drawn with smudged faces, congregated to mourn a lost life. Life, like the paint, dripped away from the body carefully laid down diagonally through the work.

The paintings, all created this year, were mostly informed by a string of real-life crises in Lagos, making the exhibition a delicate cartography of collective strife and remembrance. Omuku explained how these injustices came to take such a pre-eminent space in her work. “It got to me. It got to me and to the point where I couldn’t ignore it, and I had to start painting about it.”

It was utterly fortuitous that the show coincided with yet another political crisis. This time, Nigeria made the headlines for the repression of peaceful demonstrations against police brutality. And in a twisted case of life imitating art, “The Sit Down” became almost a depiction of reality.

It would be tempting to reduce the narrative of this exhibition to the stereotypical view of an African nation endowed with vast natural resources yet crippled by decades of mismanagement that has left the majority of the population living in abject conditions. However, Omuku successfully steered clear of such reductive views and constructed a multilayered visual narrative that highlighted the complex nature of Nigeria as a nation.

To those unfamiliar with Nigeria, the recent unrest may come as a surprise. However, it is happening on the back of recurring social and economic conflicts that lay a flammable foundation awaiting a spark to ignite. While revisiting the poignant moments that led to the current conflict, the artist put the emphasis, not on those in power, they are the ghost figures in “The Sit Down”, but on those who drew the short end of the social stick. In sorrow, in grief, in protest, they gathered, and their bodies merged to form one collective unit.

Naturally, Omuku’s views are informed by her highly emotive perspective on the role of the artist. “I think for me, the artist’s primary position should always be empathy. I think if you approach the world through that lens, the lens of empathy, you see things clearer, you speak about things in a more honest way […] Some of these paintings are my ways of mourning the people that have lost or protesting with the people that have had the injustice or sitting with the people that are asking for answers. So everything is from a place of empathy.”

Even if “Technicolour Protest” captured a flash of rage, this collective unit is mostly activated by solidarity and a deep sense of fellowship, the like of which is best described in Small Chaos. A group of bystanders turned first responders depicted rescuing children from the ruins of a building that collapsed. Time and again, the artworks reiterated people’s unwavering commitment to their communities.

The focus on people conveyed the feeling that maybe the real wealth of Nigeria didn’t lie in the underbelly of its rich soil but firmly on the ground, in its millions of inhabitants and their rich cultural heritage. A cultural heritage encapsulated in the vintage fabric, Sanyan, also known as Aso Oke. Omuku discovered the material in 2019, soon after settling in Lagos, when she asked friends to bring her Nigerian textiles. It was part of an effort to re-immerse herself into the local culture through the fabric after spending years abroad. The vintage woven textiles became “part and parcel” of her work, a conciliatory space where old and new, craft, and art meet to form new contemporaneous narratives.

At this time when political positions are entrenched in Nigeria, and dark clouds hang over the country, the symbolism of these paintings, their rootedness in empathy shine as a beacon of light for what we all hope is a brighter future.