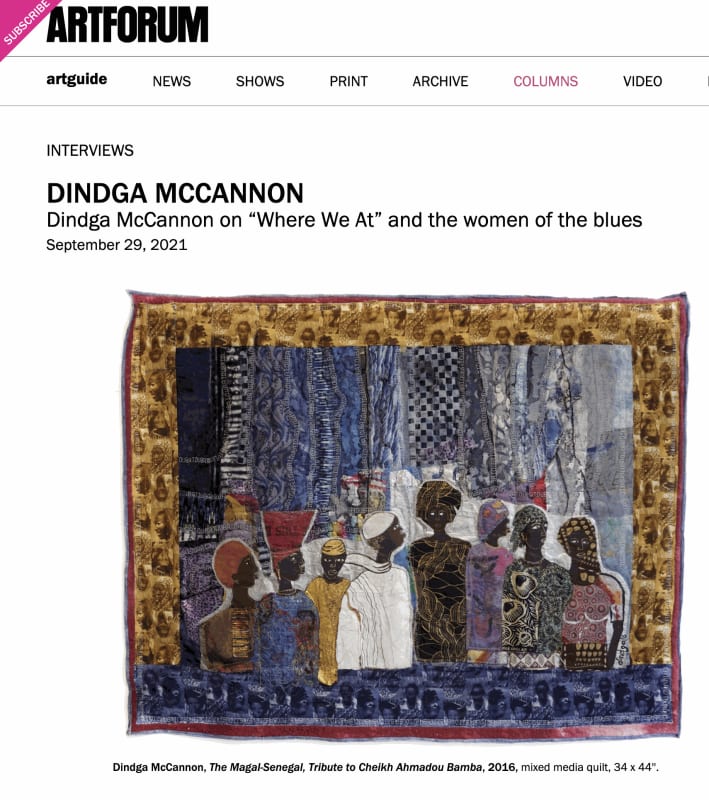

Dindga McCannon, The Magal-Senegal, Tribute to Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, 2016, mixed media quilt, 34 x 44 in.

Music seemed to melt into color as Dindga McCannon walked me through “In Plain Sight” at Fridman Gallery. The songs of Ma Rainey and Gladys Bentley played behind a recent work, Blues Queens, 2021, a shrinelike, quilt-covered column commemorating blueswomen of the early twentieth century. Footage of their performances looped in the background, the black-and-white of the videos contrasting with the textile’s shimmering blue tonalities. A key figure in the Black Arts Movement, McCannon cofounded the groundbreaking collective “Where We At” Black Women Artists, Inc., with Kay Brown and Faith Ringgold in 1971. On view through October 17 and gathering nearly fifty-five years of painting, sewing, sculpting, and printmaking, “In Plain Sight” is the Harlem-born, Philadelphia-based artist’s first solo show at a commercial gallery.

PEOPLE ALWAYS ASK me where I have been this whole time. I’ve been here all along. Whether through painting or weaving, I’m interested in telling stories of Black women who refuse to take no for an answer, who push the limits of what’s possible. The full breadth of their stories is often cut short or overlooked. Blues Queens is a memorial to female blues singers who were prolific between the 1890s and 1920s across America, to Black women who dared to be artists and take control of their careers. They performed at jazz clubs and sang songs with outrageously bold lyrics that seem impossible for the time. The work took four months to sew and build.

My life has always run in parallel with music. I used to have a gallery and boutique called the Afrodesia Mod Shop on the Lower East Side; Jackie McLean had a candy store down the block. After closing the shop, I would go out to Sluggs, a jazz club on East Second Street, and Studio Rivbea, Sam Rivers’s club on Great Jones Street, where I would listen to music and sketch musicians performing.

Rather than in photographic representation, I am interested in imaginative portraiture. My ongoing “Harlem Women” series (2015–) is partially based on photographs, but I embellish them with pieces I add around the sides of the canvases. Hattie McDaniel, who was famously the first Black recipient of an Oscar but was also a blues singer, was the first subject I painted in the series. The idea of decorating their surfaces with objects came later. After thirty or forty paintings, I lost count of their number. As I painted, I realized that the edges were begging to be ornamented as well, with tiny instruments, musical notes, microphones, Black fists, pearls . . . These found, bought, borrowed, or gifted objects add a sculptural quality to the work.

Colors, especially bright tones, amaze me. Over the years, I’ve learned to embrace this fascination instead of holding it back. Western art tends to favor muted tones, but when I visited Africa, I saw that women dress up early in the morning as if they’re going out at night. The occasional circles on the figures’ cheeks add youth and liveliness but also play with facial composition, with depth and flatness. The paintings organically reveal to me what the women in them should wear.

Dindga McCannon, Hattie McDaniel, 2021, mixed media on canvas, 14 x 11 x 2 in.

In my own life, I look forward rather than back at the past. In the painted quilt Four Women, 1988, or the oil on canvas titled The Sisters, 2020, this orientation is evident in the way that women’s hair flows backward. Eyes are important because they’re the doors to the soul, but also, they’re on the watch-out. I’ve always been very conscious of my surroundings and those who might be looking at me, and so these women are careful about the viewers around them.

I myself decided to be an artist at age ten, despite my mother’s disapproval. She was a seamstress and made me go to Fashion Institute of Technology’s high school for clothing design so I would have a skill that I could live on. I was among the first Black students to enter that department. I was overlooked by the teachers and eventually signed up for the Art Students League, where I was taught by Jacob Lawrence, Al Loving, and Richard Mayhew. I received my art education there and by attending the meetings of the Weusi Artist Collective in Harlem at the same time.

Many artists from “Where We At” eventually abandoned their art practices. Juggling art with motherhood was too burdensome. Some passed away, but those who are still around try to keep in touch. I recently reunited with former members Faith Ringgold, Charlotte Richardson, Linda Hiwot, and Ann Tanksley—Charlotte and I chatted until 3 AM. A part of the collective at the time was a solidarity in motherhood. We used to take turns and babysit each other’s kids while we worked in the studio. Most days, I would leave work around 6 PM, pour myself a big cup of coffee, and paint or sew until one in the morning—sleep was scarce. Studio time and the isolation to create are critical, but for most women, domestic tasks turn this into a privilege. Motherhood never became my subject in art. There has been enough art that limits women’s roles in society to that alone, so I made the decision to focus on other potentials for women.

— As told to Osman Can Yerebakan