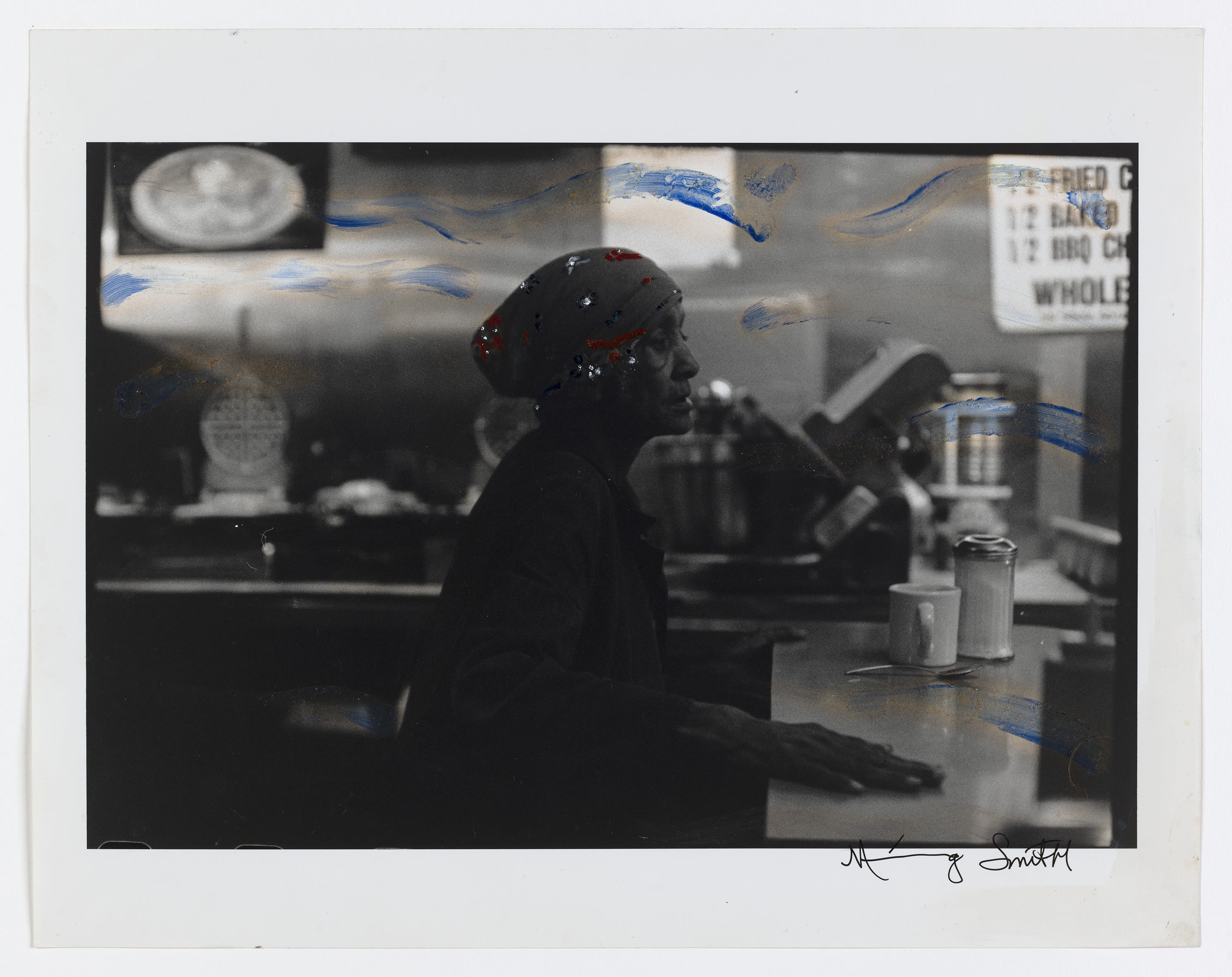

As Pippy Houldsworth Gallery exhibits her first UK solo show, the pioneering American photographer talks through some of her key images

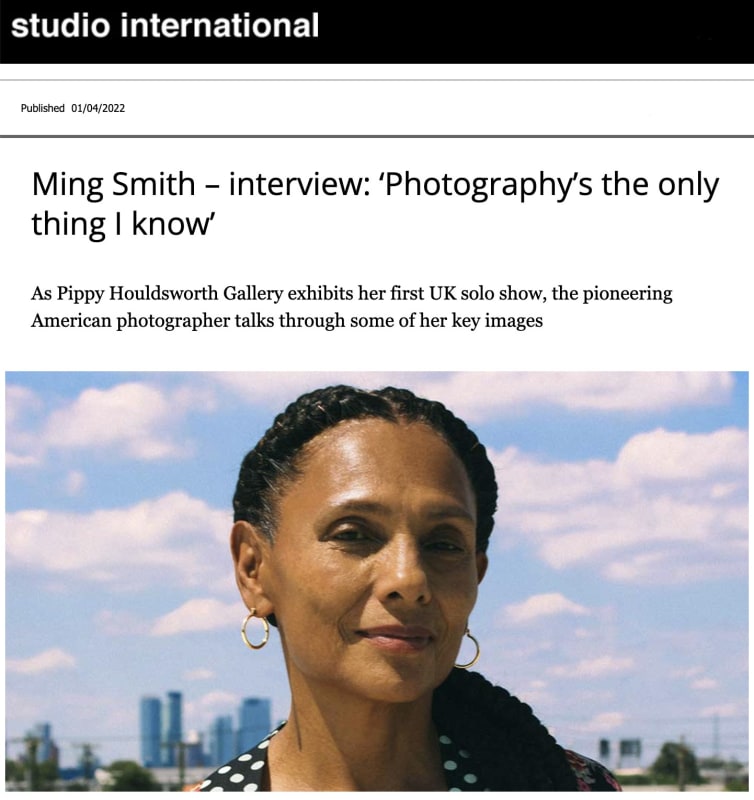

It is very dark indeed. A man sits half-visible on a tall-backed chair. The view in the window behind him reveals a blurred cosmos of lights. But one’s focus is drawn to a single smaller glow in the man’s hands. It comes from something mundane: the end of a lit cigarette. Yet it glows with an intensity that belies its humble origin. The man is Hart Leroy Bibbs, a poet, photographer and one-time actor, in the Herbie Hancock-scored jazz film Round Midnight. And his photographer was Ming Smith (b1950). “There was no light,” recounts Smith, “and I was holding my breath. And he said: ‘Do you know what you’re doing? You’re doing circular breathing.’”

Circular breathing is a technique used by wind musicians that involves simultaneously breathing in through the nose and out through the mouth, allowing for a single continuous note. It can require an enormous amount of training and focus. This makes it an apt comparison for Smith’s practice. “Photography’s really the only thing I know,” she says, “I don’t know a lot about politics. I’m completely confused about everything.” Smith is being modest: over an hour of conversation, she reveals a knowledge of much more than her chosen medium. But it becomes quickly apparent that her art and life are enormously intertwined.

Smith was in London for the opening of A Dream Deferred at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, her first exhibition in the UK. It includes silver gelatin prints of 36 works spanning much of her career, but with a particular focus on the Invisible Man (1988-91) series. Smith was born in Detroit and raised in Columbus, Ohio. Her father was a pharmacist who had once harboured artistic ambitions of his own. Smith followed in his footsteps: after medical studies at Howard University, she moved to New York to become a photographer, working as a model to support herself. It was a meagre existence. But Smith kept on shooting. “I remember one lady came to my house,” recalls Smith. “I just had a room in the West Village. All my money went into photography. And I just had photographs on the walls and on the ceiling, because I had run out of room.”

In 1975, Smith became the first woman invited to join the Kamoinge Workshop – a collective of African American photographers that emerged from the civil rights movement – where she was mentored by the late Louis Draper. “Once we were in a studio,” says Smith. “We waited almost three weekends to use it. I brought all my money, all my materials, everything I had. And then he said: ‘Oh my goodness, you didn’t bring the lens holder.’ It would have taken me months and months to get in again. And he laughed and chuckled, sort of like how Santa Claus would chuckle – he was missing teeth – and said: ‘I have an idea.’ And he took pieces of cardboard and cut them. And we used them.” Photos from this session have rough, uneven edges reflecting their improvised creation.

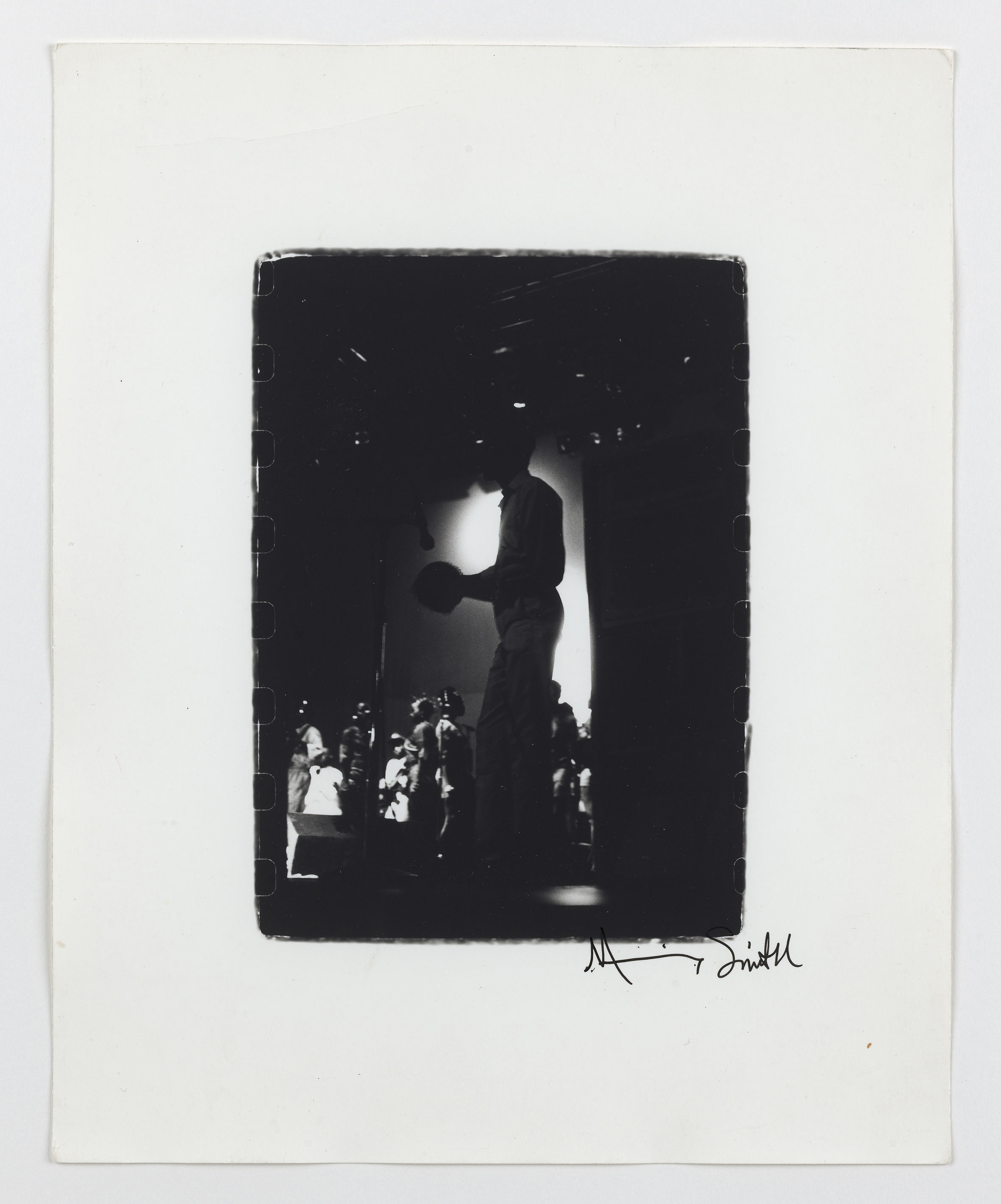

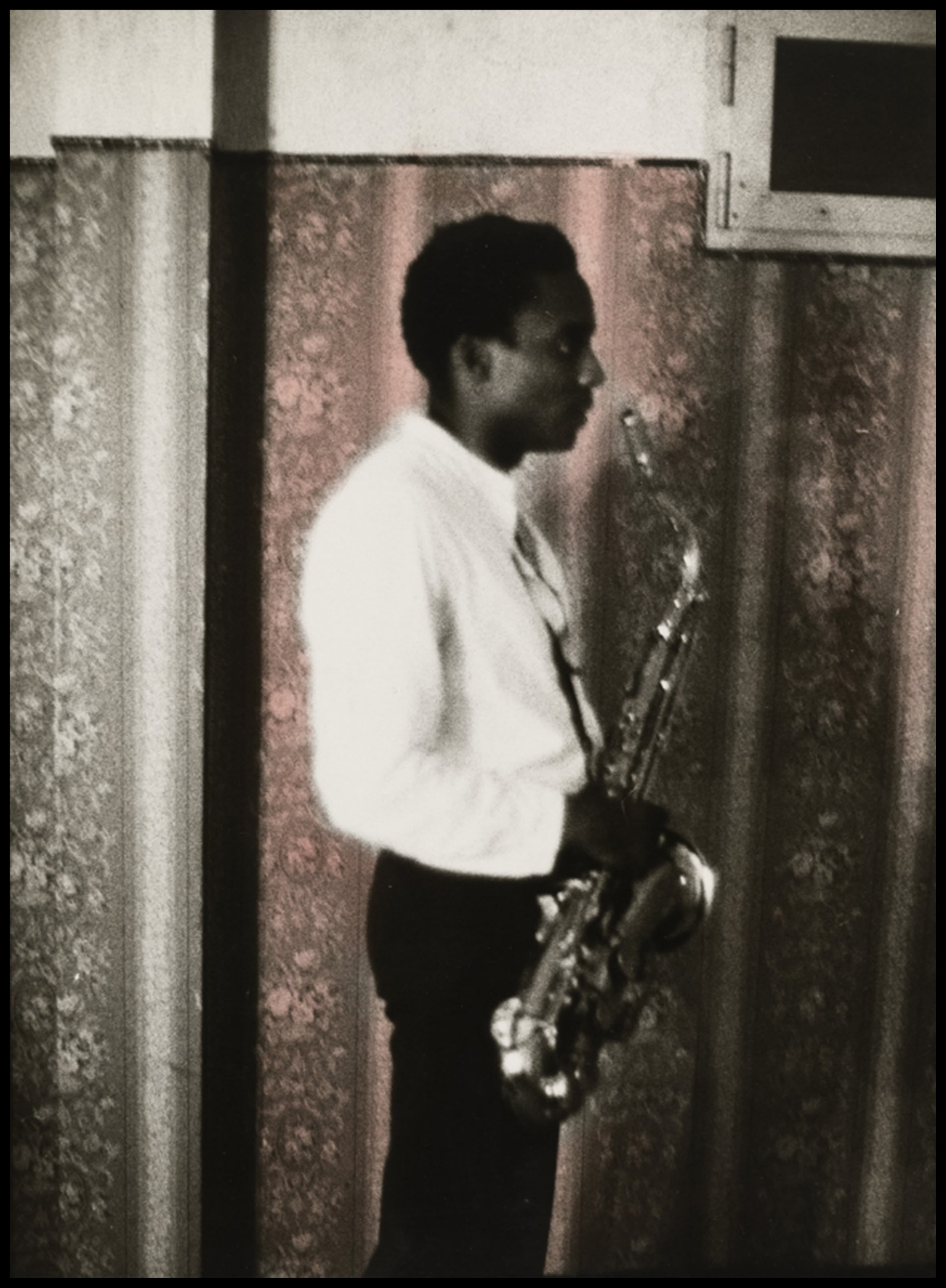

Smith gradually established herself as an artist concerned with African American life, though her range is far broader. Her subjects include a dazzling array of cultural luminaries. Many are black musicians, among them Nina Simone, Sun Ra, Grace Jones, Tina Turner and Pharoah Sanders. But she has also captured wider cultural figures: dance pioneer Alvin Ailey, writer and activist James Baldwin and the pioneering photographers André Kertész and Brassaï. Her portraits are seldom straightforward. She caught Brassaï, a longtime hero, at an exhibition opening in 1979. The aged artist looks straight into the lens. But the composition – Brassaï’s left arm out of shot, a framed print half-visible on the wall behind him, an umbrella on the table next to him – is beguilingly off-kilter. “He put that umbrella there,” says Smith, “to help me make a better photograph. It was a communication that he was giving me.”

Despite depicting figures from life, Smith’s work is seldom documentation. But it is stranger and more personal. It presents an America of fleeting impressions, subjective rather than definite. “I have a body of work,” she explains, “but it comes out of my life.” Many of her images feature oblique angles, minimal light sources and blurred elements created by using a slow shutter speed. Some – such as Nuns on the Square (August Moon Series) (1991), showing a Pittsburgh cemetery where a real or stone nun prays before a statue of the Virgin – have an element of surrealism.

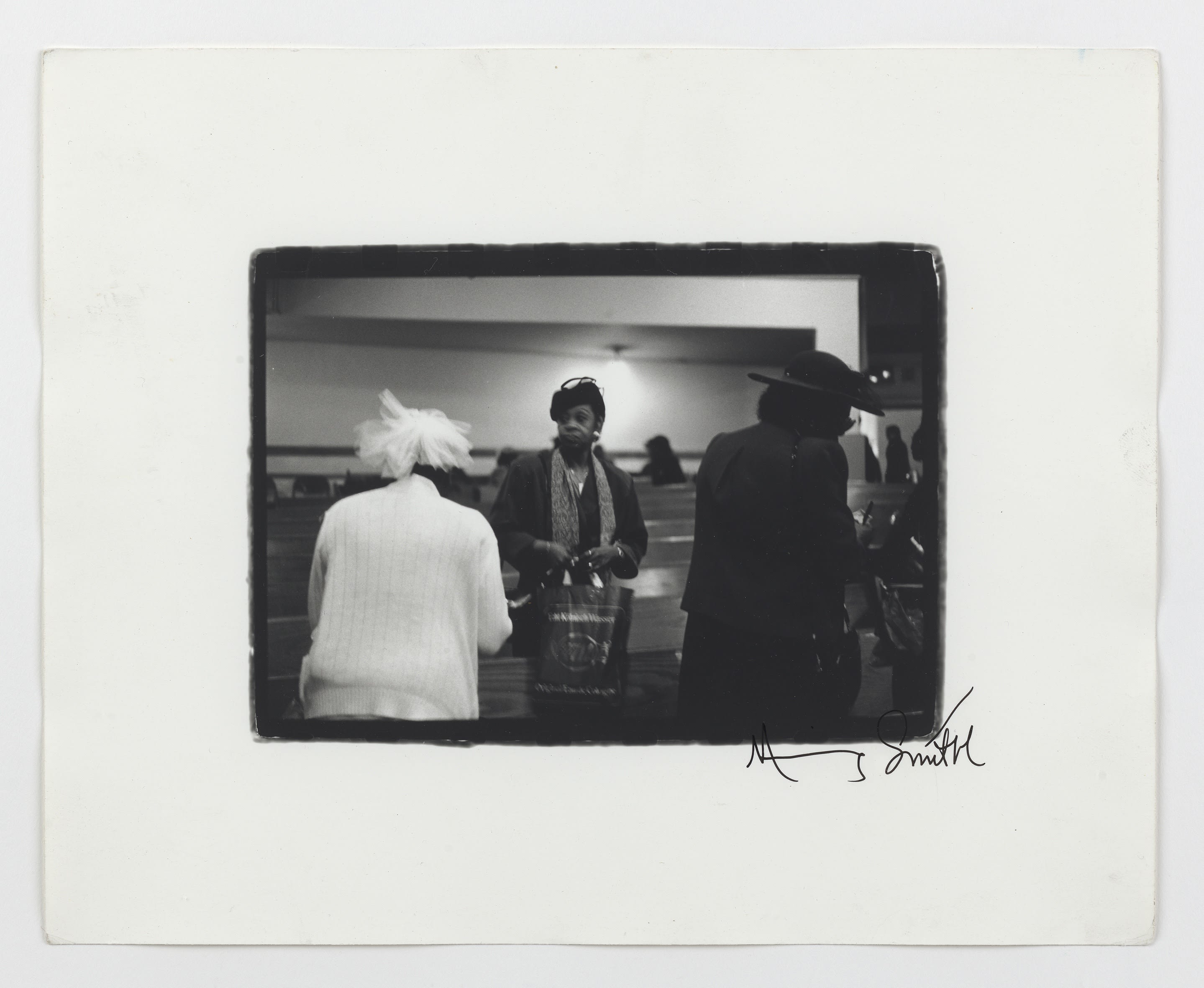

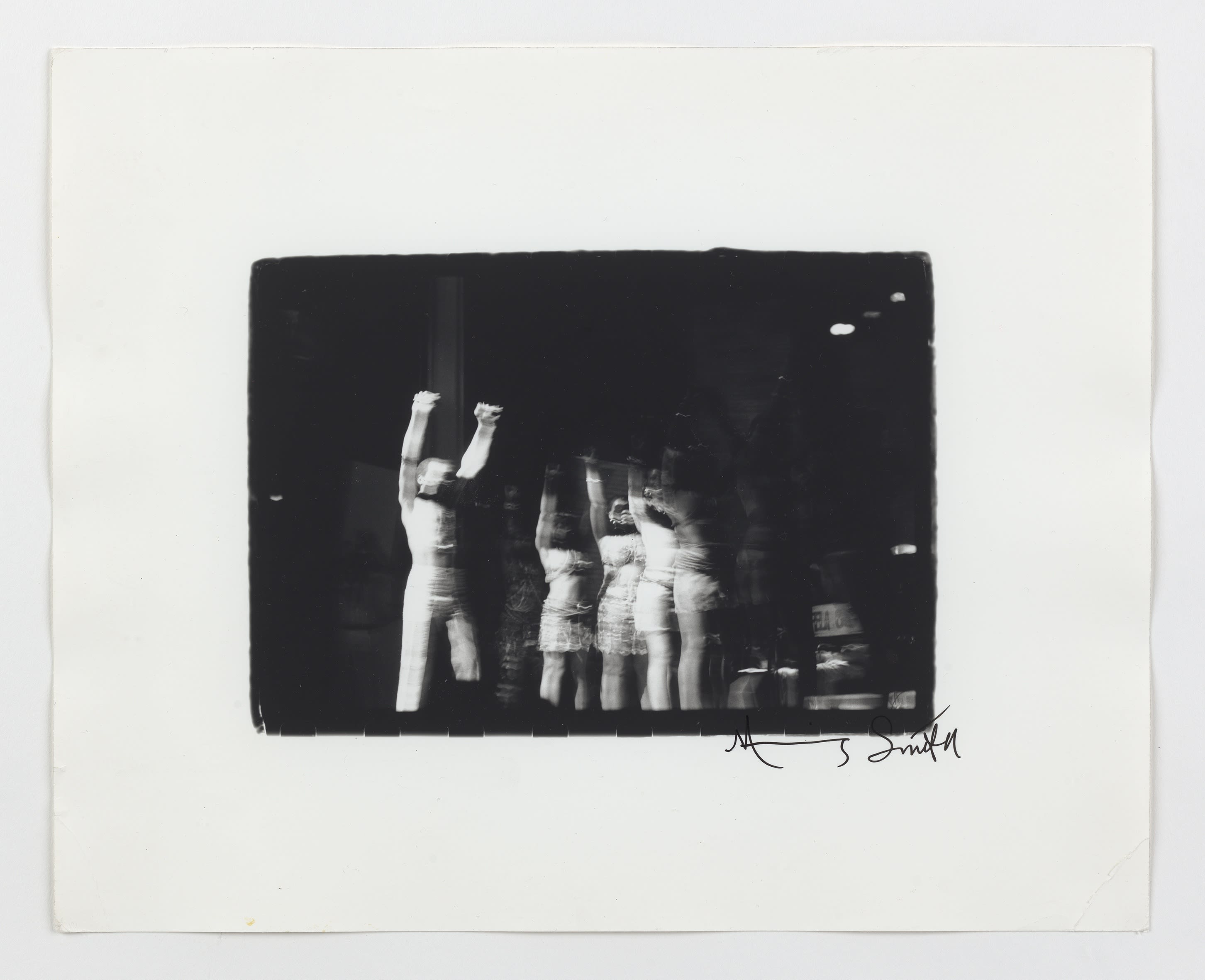

There are curious distortions and absences. Fela Kuti and his band seem to melt into each other, their features obscured, as if they have become music itself. One 1978 work purports to depict the jazz singer Betty Carter playing an end-of-year gig. But Carter herself is not visible across the balloon-filled room. “She wasn’t in this picture,” explains Smith, “I wasn’t close enough. But the feeling of New Year’s Eve at The Bottom Line …” Smith coated the photograph in brownish-pink paint, to enhance the mood. “I did my pink period,” she recalls, “like Picasso’s blue period. So, I did a lot of different things in this colour.” Feeling and ambience can matter as much as the subjects shown.

They often have a story attached, tying them to a moment in Smith’s life. Sun Ra Space II, New York (1978), which shows the jazz composer, poet and mystic as almost an apparition, clad in turban and diaphanous cloak, came about by happenstance. Smith says: “One of my friends was going to a dance with Sun Ra, and I went because he was going. I think it was free, or it wasn’t that much. But I went. And that’s how I took a photo, because of a friend. And my whole life has been like that really.” Smith sold the photo to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), making her the first female African American photographer in its collection.

For the Invisible Man series, named after Ralph Ellison’s extraordinary 1952 novel, Smith roamed at night, creating a nocturnal guide to Harlem. She captured both empty basketball courts and bustling streets. There are residents of all shapes and sizes: young bucks in exuberant patterned jackets, grannies heading to church. People gather beneath the Apollo Theatre’s beacon-like billboard, while light glows from a West African restaurant. One of the most striking images has a stoop in almost pitch darkness, with the outlines of two figures barely visible on the steps.

There was a point when Smith was in danger of becoming invisible herself. But recent years have seen interest in her work grow and grow. In 2017, she featured in the Tate’s revelatory Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. She has embarked on a series of collaborations with video artist Arthur Jafa, including a recent shoot in a plantation near New Orleans. Her practice has grown too: since the turn of the millennium, Smith has returned to using paint, applying oil directly to prints in expressive daubs. “I follow my impulses, I follow my spirit,” she says, “And I also feel that God leads me, and so I kind of go with that.” Perhaps we, in turn, should follow where Smith leads.