Ming Smith is a Black female photographer. When she first dropped off her portfolio at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1978 the receptionist assumed she was a courier. When MoMA offered to buy her work she declined at first because the fee didn’t cover her bills. Luckily for us, she relented.

Later she said that, "Being the first Black woman photographer to have a work acquired by the MoMA was like getting an Academy Award and no one knowing about it."

Smith was the first woman to join the Kamoinge Workshop in New York in 1963, a pioneering group of Black photographers who, she says, “introduced me to the idea of owning the images we saw of ourselves”. She has been widely exhibited in the US and has participated in exhibitions in the UK. Now the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery presents A Dream Deferred, her first physical solo show in this country, following up on the gallery’s 2020 online show Painting with Light.

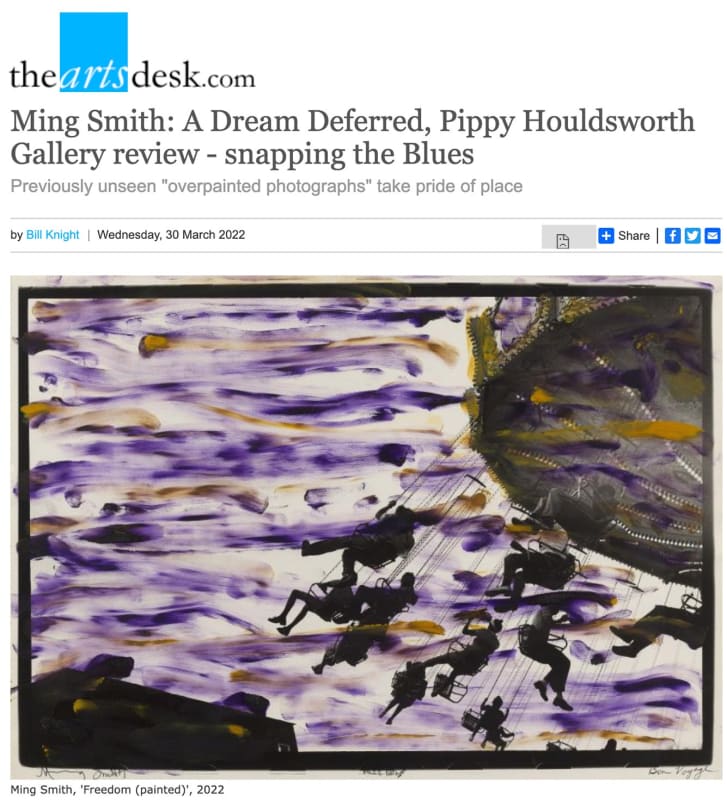

Smith has a large body of work recording and celebrating Black life in America and Africa, but pride of place in this show is given to a selection of her previously unseen overpainted photographs Freedom (painted), (main image), shown alongside vintage prints from her Invisible Man series, 1988–1991, whose title is taken from Ralph Ellison’s book of the same name. The Invisible Man images are small and they are often fuzzy and dream-like, designed to show us feelings as well as facts (pictured above: Ladies in Church). The narrator of Ellison’s novel is a Black man who is invisible "simply because people refuse to see me." The white man is conscious that the man is Black, but not of his humanity. Smith makes the human visible, and that is the core of her work. By dragging the shutter and taking multiple exposures she makes us see the movement and latent energy in the scene before us - she makes her images shimmer and live. No light but rather darkness visible.

What does the overpainting add to the photographs? The answer given by the gallery is a heightened emotional resonance, but to this reviewer it’s more about movement. You get the feeling that in a lot of her work Smith wants to reach beyond the still image. These overpainted photographs have the same impact of movement as the long exposures. They cease to be stills and become something else.

Key historic photographs from the early 1970s to the late 1990s are also on view and these are treasures. Smith has a wonderful eye and when she simply records the scene the image leaps from the wall (pictured above: Mother and Child, Harlem, New York 1977).

Smith has said that her photographs are "like the blues". They celebrate, they mourn, and they sing. This is soul photography.