As Nengi Omuku’s solo exhibition ‘Gathering’ reopens in London, the artist discusses how her interest in crowds was inspired by protests in Nigeria and her own isolation

Nigerian artist Nengi Omuku’s latest series of large scale paintings – currently on display in her solo exhibition Gathering at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery London Bridge – mark a shift away from singular vibrant portraits to groups of spectral figures who appear, at times, to be fading, streams of watery paint dripping down the surface.

Though classically trained, Omuku paints onto a traditional Nigerian fabric known as Sanyan, giving her works a distinct physical quality that links to her central thematic focus on representations of the body in relation to cultural identity and emotional turmoil.

These latest works are based on archival and press photography which the artist selected during her research into why and how people gather, and whilst it’s no coincidence that many of the scenes resonate with protests and collective mourning across the globe, it is the negative space that makes these works so haunting.

In the work entitled Room with a View, for example, the patterned floor is the most concrete element whilst the painting’s protagonist – a woman – is smudged and dripping; the sofa on which she is lying seems to have been erased; and her shoes are blank space. The effect is strangely destabilising – the image itself appears to be wavering, immaterial. Added to this, the fabric itself contains tiny holes and when the works are hung away from the wall – as they have been in the show – the light passes through to create ephemeral patterns that appear almost like the painting’s ghost, or, if we were to really stretch the concept to its limits, a kind of spiritual abstraction. In any case, it makes for an intriguing viewing experience.

Millie Walton spoke to Omuku about some of the inspirations behind these works and the evolution of her painting style.

When did this latest series of paintings begin?

The work about protests and collective mourning started at the beginning of the year. The first painting I made was the piece called Gathering and that was based on photos and press images of a building that collapsed near my studio and people coming together to rescue or to mourn. It was a horrible thing that happened, and as the year progressed, a lot of bad things were happening in Lagos and so it became really hard for me to paint pretty pictures. I felt that I didn’t have the luxury of painting things that just made me happy anymore; I had to start looking outward, and speaking about things that were happening in Lagos.

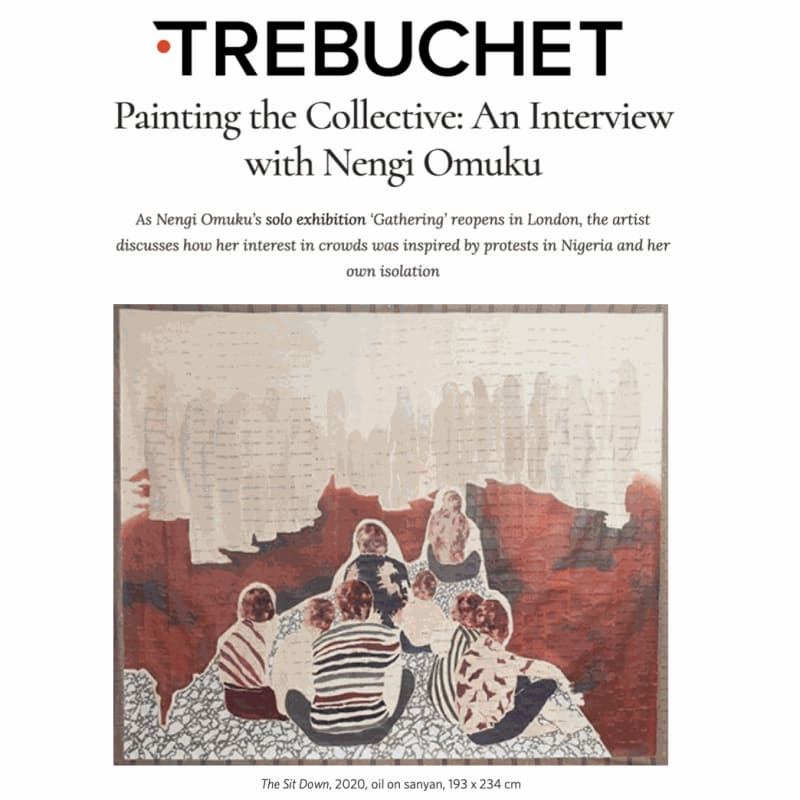

After that first incident, came mass unemployment for the public transport workers who quietly protested and the government shut them down. Then, Covid hit and reliefs were apparently given out, but no one received them. Recently, stories are being released about politicians who stored all of the reliefs in their houses and are saying ‘Oh yes, we kept them for our birthday parties and then we were going to give it out,’ which is so ridiculous. Some of them are so out of touch with reality. All of this, I think, is what inspired the artwork The Sit Down which is one of the largest pieces in the show. One day, I had this very strong image in my head of people sitting and appealing to a crowd of people in the background to make things better.

Three days before I came to London the end SARS protests began. People rose up collectively and started protesting. Nigeria is a very divided place. There are so many different groups of people who have been forced to exist as a unified entity, but the end SARS movement was a unifying force.

I was already aware that the work I had been making throughout the year was beginning to resonate on a different kind of level because of the protests and then two days after I arrived in London, the Lekki massacre happened. People were peacefully protesting in Lagos and a stream of military personnel opened fire. The protestors were told if you sit down, wave the Nigerian flag and sing the National anthem it’s against the law for the police to attack you, I don’t know if that’s true, but that’s what they had been told and that’s what they did. There are videos of them sitting and singing. Still today, they don’t know how many people died and there are rumours that some of the bodies were stolen to hide evidence.

Do you think that these contexts have or will change the way your viewers perceive the work?

I began painting the scenes just before the Black Lives Matter Movement started in the US and a lot of people were asking me then if I was painting about BLM and I said, ‘No, I’m painting about a black experience and what’s happening in Nigeria.’ Now, a lot of people have asked me whether it’s about the end SARS protests, but if people relate to the images based off what’s happening in Nigeria at the moment and the use of gathering, that is enough for me. I’m not too concerned whether people think the work was reactionary or preemptive just as long as people can relate to the work.

Crowds and the idea of gathering more generally has taken on huge significance since the beginning of coronavirus. Was that something you were also thinking about?

Yes, it was my own isolation that made me start looking at groups of people and how and why people gather.

What inspired you to start painting on sanyan fabric?

What drew me to fabric in the first place was noticing, after I’d moved back to Nigeria from England, how clothes that people were wearing were used to identify where they came from. Dress is a really big thing in Nigeria and each state and tribe has their particular dress. So, in each state I went to, I started to ask people to bring me their traditional materials. At first I noticed that people were wearing a lot of dutch wax print which people call African print, but it’s not actually African. I wanted to look deeper to a pre-colonial understanding of dress in Nigeria. I asked people to bring vintage fabrics and I started by using those as inspiration for clothes for the bodies that I was painting.

Then when I moved to Lagos, someone bought me Sanyan, which is a pre-colonial material originally made from silk and industrial cotton produced by moths in northern Nigeria and transported down to the west for trade. When I saw this material, it was like a spiritual experience for me; the feel of it, the craftsmanship, its history and age. I wanted this fabric to become the body of the work, and it has changed the way I paint because it’s a very rough surface. My brush marks are much looser and my style has adjusted.

In many of these paintings, you’ve left large spaces of raw fabric. Is this because you want the viewers to notice the surface?

It’s two things really. When I was painting on canvas I would sometimes cover the entire surface because it was about image-making and when I started working on Sanyan, the first few paintings were the same, but recently, I realised that there’s so much beauty in the rawness of the surface. I also wanted to leave breathing space within the work so that I’m not entirely dictating how the viewer should feel, and so that the surface can speak for itself. I want the work to be more like a collaboration between this ancient material and oil painting which is also ancient but from a different tradition. I’m Nigerian, but I’ve been trained in a very western way of making art, and I want those two things to breathe on the same surface and have equal weight.

The blank space combined with the faceless, dripping figures gives the work a surreal, dreamlike quality. Is that important for you?

I’m glad you say that because even though my works may sometimes appear figurative, I’m always thinking about how you paint the mind. That’s really the initiating point for the mark making. I want to show the body as multifaceted and in motion. We may appear one way from the outside, but there’s a lot of inner turmoil that goes on within, psychologically. The way in which I paint the body evolved out of my interest in mental health and a person’s psychological space. I was interested in how you begin to talk about trauma, anxiety and emotions through painting.

The absence of faces seems to fit with that idea and is also suggestive of a kind of anonymity or universality.

Yes, absolutely. I want the work to be relatable. It’s about the experience of being human – that’s really what’s at the heart of it. The qualities of being human, in spite of race or nationality or whatever. Of course, I am painting from the perspective of a black woman but I still really want to touch other people’s lives, for them to be able to feel and relate to the work.

In the past your work focused more on the female body, but these works seem to feature more masculine figures. Was this an intentional shift?

Some of the bodies in the foreground are male, but it relates specifically to what I’m painting about at the moment which is the unrest in Nigeria and there were a lot of male figures in the source photos that I was looking at. To be honest, though, I see a lot of the bodies becoming genderless. I’m not really describing bodies based on gender.