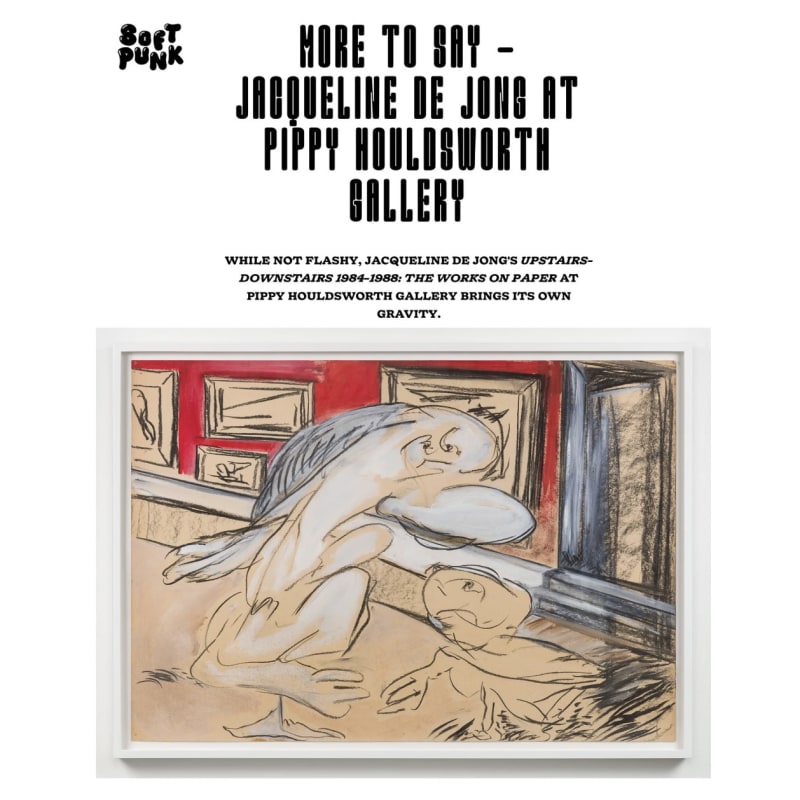

Perhaps there is not much that is visually arresting to the viewer when they first enter Pippy Houldsworth Gallery’s new exhibition, Upstairs-Downstairs 1984-1988: The Works on Paper, a collection of works produced by Dutch painter Jacqueline de Jong, running until March 12th. Beautifully framed, this group of 14 studies, precursors to the 27 site-specific works de Jong made for the 1988 opening of the Amsterdam city hall is, on first glance, more sedate than what we might expect today, or at the very least, from behind their anti-reflective glass, more detached.

Still, as one walks around the room, there is a weight to de Jong’s work. Ghoulish figures, if not overtly threatening, keep the viewer on edge. Their mischievousness leaves room for fear, even if they do not demand it. But there is more — de Jong inspires a reverence that is rarely achieved in contemporary art. Her product is resolutely sincere with what Julia Felsenthal referred to as an “[allergy] to anyone telling her what she can and cannot depict”. De Jong’s work is a reminder that art history is not something of the past, but is very much alive, and that its practitioners continue to contribute to our era.

It does not hurt that de Jong’s life has taken liberally from the annals of the post-war European tradition. Her early work, as Felsenthal notes, is reminiscent of the CoBrA movement — not least because Asger Jorn, a co-founder, was a former partner. She too was cast in the socio-historical crucible of the Holocaust, briefly moving to Switzerland as a child to evade capture in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands. She came of age among Europe’s modern masters, not as a bystander, but as a full participant in their milieu. If her work feels as if it reflects a time now past, it is because it does; at 82 years old, she remains a relic of an older generation.

That does not mean, however, that her work lacks contemporary import. The ghostliness of her paintings, paired with their excitement and sly visual innuendos, feels apt for our moment; a Europe on the brink war. It is the brimming potentiality of her work – the viewer always remains party to an incipient happening – that strikes a chord. Much as in politics as in art, the lines between future and current crises is very thin indeed. In this light then, de Jong’s work takes on a sickly irony: produced in celebration of a modernized future, her paintings recall how quick history is to repeat itself.