Usually around this time of year, I start to get that odd cocktail mixture of excitement and anxiety as my extended family prepares to gather from all corners of the globe for a New York City fiasco of cooking, eating, shopping, sightseeing, movie watching, laughing, yelling, debating, mood swinging—an extravaganza also known as the Christmas holiday. But this year, as the whole world already knows, is different.

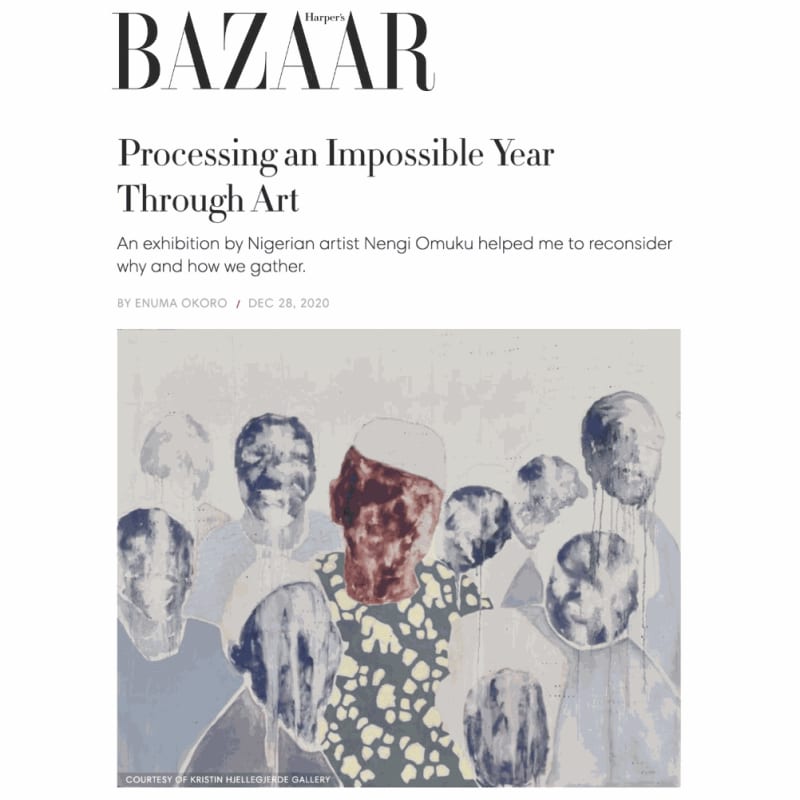

Omuku’s solo exhibition Gathering opened November 5 at London’s Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery. For the past month, I’ve been returning to gaze at several of the figurative paintings that all, in some way, consider what it means for people to gather as a community and move as a collective, and what it could mean to be part of a community but still, for various reasons, exist on the outskirts of it. The images are painted in oil on beautiful strips of Sanyan, a traditional vintage Nigerian fabric worn in colonial days primarily by members of wealthy western Nigerian families. Originally created from woven threads of wild moth silk, new swaths of Sanyan are blended with industrial cotton. Omuku is new to using this fabric as part of the larger conversation she’s evoking through her work about collective identity, body politics, and communal narratives.

This focus is a shift in attention for Omuku, who is used to reflecting primarily on the interiority of individual subjects as they navigate place, identity, and belonging. But in the past year of bearing witness to social injustices and broken social systems both in her native Nigeria and around the world, Omuku began thinking more about collective identity and how communities of people navigate experiences of trauma, injustice, and misfortune. It is something we have all had to think about, with the entire world experiencing this pandemic at the same time. Caught still in the grips of the virus, we are left wondering what it looks like to process grief collectively.

Omuku’s paintings focus on the psychological space of the collective, and in this recent exhibition, she aims to capture within the bristles of her brush the spirit of Lagosians during a season of life when things in society at large were not running as they should, even more so than usual. Three particular events influenced Omuku’s new work. The first was the sudden 2020 governmental ban of three-wheeled taxis and mopeds by which many Nigerians not only made a living, but also used as a major source of transportation in a highly congested metropolis. The ban left countless people unemployed and struggling with new challenges of navigating the city. The second event was the 2019 collapse of a three-story building housing a nursery and a primary school, and in which many children and adults died. The third event was the onslaught of the globalpandemic.

Speaking to me from the London gallery, Omuku shares, “I wanted to try and convey what was going on mentally in response to the breakdown of governance, the injustices apparent in certain segments of society, and the lack of adequate response to collective tragedy and public trauma. While painting, I was reflecting on what it would be like to represent inner turmoil, troubled mental and emotional states, through how I depict bodies.”

In her painting What Was Lost, four people are sitting and standing at various distances from one another. Their bodies are roughly outlined human forms with little to no detail of attributes of gender or distinct personalities. They almost float on the fabric like human casings of what once was. Clothes fuse into skin, which fuses into setting, which fuses into landscape. There is a blur of boundaries between interior and exterior space. The painting was completed during the first wave of global lockdowns while Omuku was completely alone for several months, unable to visit family or friends. “I was mourning my community and the usual ways we had of gathering together. It felt like a big loss I couldn’t yet articulate,” she says.

Through this piece, it is as though Omuku was contemplating what it felt like to be suddenly isolated physically from one’s community while also still holding them present in this collective experience, how trauma and grief can hold people both together and apart simultaneously, physically and emotionally. It is also a reflection on people’s sudden separation from the outside world, losing basic freedom of movement once taken for granted by so many, and how quickly our natural environment can change and alter our daily lives. “I was trying to process this new reality of having to remain indoors because of this invisible enemy, and yet, I could still see the outside world from my large studio windows.”

For Omuku, this overlap of physical spaces in her work is a cue to viewers of her own ongoing attempts to think about what’s happening in both our created and our natural environments. “I’m still processing what I see and experience in the world as of late,” she says. “How so much that happens to us as people and communities and in the world as a whole appears illogical.”

Given the safety guidelines, our bodies are still renegotiating how to be with other bodies in spaces once so free and unthreatening, and we’ve had to contend with thinking consciously and conscientiously about decisions of gathering for the sake not of our individual pleasures but rather for the sake of the greater communal good. These are global concerns affecting everyone.

It seems apt that there are no faces on any of the figures in What Was Lost (or any of Omuku’s other paintings). The intentional ambiguity suggests that even though these visual narratives are centered in Nigeria, these collective human occasions could be any community of people’s experiences. One thing the pandemic has done is unify people across the world in regard to how we move as a collective in response to the needs, dangers, and risks of certain communities, and the glaring disparate realities between people who share the same cities and countries.

We’re having to reckon with how our belief systems, assumptions, and actions also take up space in ways that possibly crowd out not only the needs of others, but sometimes even the humanity of others. Many of the paintings in Omuku’s exhibition offer glimpses into emotionally fraught and layered stories of vulnerability, pain, grief, courage, and despairing frustration over life’s seemingly illogical injustices. The images are like scenes that invite the viewer to step back and consider what makes people gather in their own communities.

In Small Chaos, a group of faceless adults gathers around a child who is being carried upward from circumstances hidden from the viewer, presumably the concrete rubble from the real-life tragedy of the three-story building collapse. A collective of bodies in various states of dress and undress fills the silk canvas, as people from all walks of life in the visual narrative world crowd in to help the young victims. For Omuku, who based this painting on a collage of images showcasing the rescue process at the scene of the accident, it was to depict the spirit of how Nigerians often band together to resolve matters on their own when public service organizations are lacking in assistance. “It speaks to experiences of when a collective mentality is used for the greater well-being of others, whether that is towards healing, justice, or creating safe spaces.” The inhabitants of her painted communities respond to the illogic and unjust chaos of their world by gathering to protest, bear witness, grieve, and take justice and salvation into their own hands.

Omuku’s work begs more personal questions of the viewer. Who, in the daily worlds we normally inhabit, are we collectively in unified purpose with, seeking justice for, grieving for, helping out of collapsed systems, and bearing witness for? Because if anything, this year has called us to think more deeply about how we gather and for what purposes. Whose well-being is at stake when we come together physically or ideologically, or when we fail to gather as a collective moving toward both healing and justice?

In 2020, people in America gathered not for the usual summer picnics and musical festivals, but for Black lives. In Argentina, people gathered in protest opposing violence against women. In Bangladesh, people gathered for anti-rape protests. In Nigeria, people gathered against police brutality and corruption. And in other countries around the world, people gathered to protest, bear witness, grieve, and speak out for justice for the collective well-being and safety of the larger community. Everything is changing. But how we individually choose to gather, for what purposes we come together, and move toward a better future will have a collective impact on everyone.