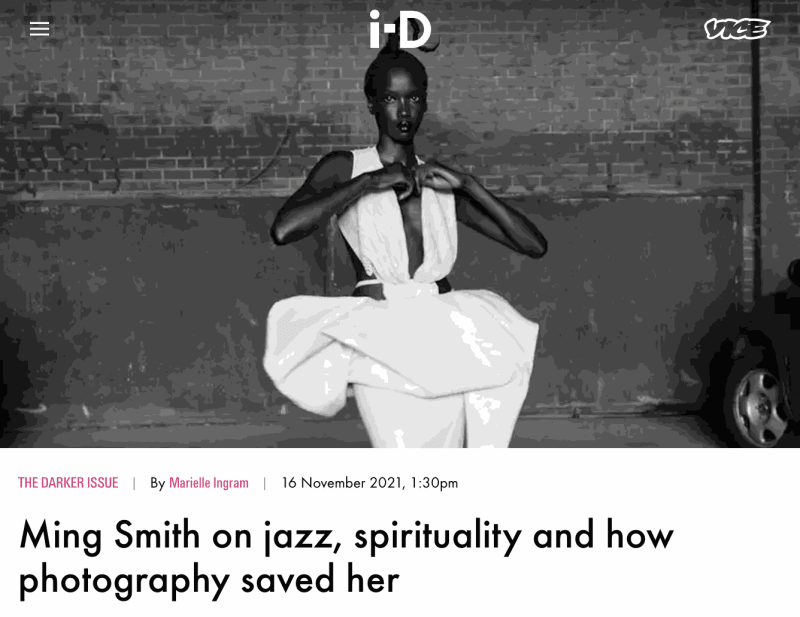

Ming Smith is the first African-American female photographer to have her work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. She graduated Howard University with a focus in microbiology and came to New York to be an artist and modelled as a way of supporting herself. In her photography, Smith finds inspiration in jazz, spirituality, and the everyday creativity of Black life. She is known for her images of Sun Ra, Randy Weston, Pharoah Sanders, Betty Carter, and other jazz musicians who were the main founders of afro-futurism and the New York jazz scene.

Ming, it’s so great to speak with you. I’m wondering if we can start off by talking about the beginnings of your artistic practice and growing up in Columbus, Ohio.

I felt isolated in Columbus in many ways, although people used to say my house was magical when they came over. We had a lot of paintings. I had magazines. I had visual material around me. My father made sculptures and my mother did embroidery. It was just a way of life to me, to look and to see. I was mostly influenced by painting. I started looking at paintings at a young age, not at photographers as much. I didn’t think to look at photography as an art form. But I was always aware of the pain that people were going through within my family and even with my friends. I was always, from an early age, an observer as an artist.

Do you think there is a relationship between your early interest in painting and some of your works in which you paint on the photographs themselves?

I feel my best work is when the photograph itself looks like a painting, when photography becomes like painting with light.

Were you interested in painting as an art practice? Or working in any other mediums like film? Your photographs have such movement to them.

Quite honestly, I think I mostly learned to shoot in black-and-white through watching films. I used to go to all of the movie houses when I came to New York in the 70s. I used to go to one film house after the other.

I’m also a dancer. I spend as much time dancing as I do photography. I’ve always been inspired by Katherine Dunham and have travelled to different parts of the African diaspora. I’ve drawn inspiration from the placement of arms in different African dances, the rhythms, the spirituality, the ceremonies, the folklore.

When I first saw ballet dancers in Ohio when growing up I didn’t even have the right words to describe it. Even when I came to New York, one of the reasons I wanted to come in the first place was to take dance lessons. I ran away so that I could take dance classes in New York.

You ran away?

Yes. The act of running away from conventional life to live the life of an artist was an act of commitment for me because I ran away from something that was supposedly safe to something that was beyond my imagination.

Once you moved to New York, what were the major breakthroughs in your work?

When I first moved to New York I wasn’t really photographing as much because I was visiting different dance studios. I would go in and I would see something new. There was a complete world around dance and around Jazz which I became a part of. To me, Jazz is America. It is the first high musical art form originally from America. It’s the music of Black Americans. It is a serious invention and concept that encompasses the struggle of Black American from down blues, to gospel, to spiritual, and Afro-Futurism. To me, it is the alpha-omega. A conundrum and omniscient.

But I knew I needed to find my own voice in photography. I think my breakthrough was when I started honing on being present by breathing. I do circular breathing, a system of breathing patterns which allow a musician to sustain notes without a break. This allowed me to find my voice, which I call soft focus and which Arthur Jafa has called the blur. It allows me to capture more than what we know to be present in the physical world.

Spirituality often comes up in your work as well.

Arthur Jafa talks about the spirit all the time, too. In his films, people are getting the spirit. I had a friend who went to Catholic Church and I would go with her sometimes. I thought it was so mysterious. They have the incense, the lights, the smoke, the windows; you have to get on your knees, stand up, open your mouth and take the flesh. It’s all very dramatic. It was another sense of beauty.

When I was young, my grandfather would take me to the church, and I would witness people ‘getting the spirit’. I was terrified because I was so shy. I was worried that if I got the spirit, everyone would be looking at me and I would be totally out of control. Now, even with my photography, I feel the spirit but it allows me to control it. Photography is like a go between. You have to be able to go into yourself, be with yourself while you’re at the same time looking at something outside of yourself.

This reminds me of how you’ve said before that photography saved you.

I would say that photography saved me in that it gave me a life of honesty. I was such a shy person but photography allowed me to be present while hiding. I probably wouldn’t have gone out anywhere in New York if I wasn’t shooting.

Do you think photography allows you, or helps you, to believe in some sense?

Seeing is believing. It’s all intuition, connection to the higher power. I think it is in Black peoples’ natural disposition to be creators.

Before I let you go, can you tell me what are you currently working on?

Right now I have a museum show in Texas. I’m focusing on that. I’m also working on a book called August Moon. I started it in the 90s when I hopped on the Greyhound Bus to visit August Wilson’s hometown, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, to photograph some of the sites that are featured in his plays. I’m in the process of editing it now and it should come out next year some time.