Ming Smith will tell you that the essence of her great ability is instinct. That great ability—photography—is also a calling and, by most visible accounts, cosmic work. Smith was born in Detroit and grew up in Columbus, Ohio. She tethered herself to photography at an early age and swiftly exhibited an aptitude for it. After studying at Howard University and moving to New York to work as a model, Smith became the first and only female member of Kamoinge, a collective of Black photographers founded by Roy DeCarava, and the first Black woman photographer whose work was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Her practice is a tale of four decades spent examining transitory occurrence—intervals at which figures blur, atmospheres alter, light shadows, vistas haunt, souls whir, and opposites engage in allied work. This is the domain of the mystical, the oblique, the seen and unseen. Smith’s approach is both scientific and celestial, and experimentation and adventure mark her fascination with detail as it stretches across form and mood. Lessons from her early life bear continually on her being, and her dedication to music, dance, and theater underlines the synergistic excellence that characterizes her secondary, if metaphoric, occupations as anthropologist, historian, and poet. Fundamentally, she employs the inexhaustible property of energy to cradle her work. It is a pact with the universe that guides her wittingly, in the same way that genius acknowledges a greater, infinite force as its wellspring. On the occasion of her recent monograph Ming Smith, published by Aperture, and the exhibitions Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, I am delighted to conduct this interview as a prelude to my gallery’s inaugural exhibition with the artist.

NICOLA VASSELL I’d like to mark this point in time, because we’re going to travel. Let’s discuss how you feel about being an artist right now. What does it mean to be Ming Smith in 2021?

MING SMITH That’s the heaviest question up front. There’s conflict in the world and conflict within ourselves. We’re in lockdown and cooped up, so it’s given us time to reflect. I’m continuing to do my work under dire circumstances, but it’s been that way from the beginning. I’ve always worked in solitude, it’s nothing new. Everyone around me is in solitude as well, so people are living in enforced isolation rather than choosing to withdraw, and that friction is real.

NV You were born in Detroit and grew up in Columbus, Ohio. Talk about your Midwestern upbringing.

MS The main lesson I learned growing up was hard work. Hard work and being a good person. We had Jim Crow, the Ku Klux Klan, and segregation, but we took every circumstance and made the best of it. We never talked about the ills, only about moving forward with positivity and love.

NV Your first official photograph is Fifth Grade Friends [c. 1957]. You took it when you were of single-digit age. Even at that early point, it shows your facility for capturing the liminal, the crux of a serendipitous moment. How did it happen?

MS My father was a photographer, he had an Argus C3. My mother had a camera also; it was a Brownie and hung in the living room coat closet. She never used it, so there was always fresh film. I went on an elementary-school outing and took photographs of my friends in class. We went to see a big public sculpture of Christopher Columbus that had been newly gifted from Italy, so that was the setting.

NV You moved to New York in the early 1970s after studying microbiology at Howard. You did some modeling, then joined Kamoinge, a collective of Black photographers founded by Roy DeCarava. What was it like making your way through the rough streets of New York?

MS Well, I could hide out. I could hide out before going on modeling assignments by putting on an old raincoat and hat. That way I wouldn’t be harassed going onto the 2/3 subway downtown from Harlem. But really, when I came to New York, it was pure magic. My first agency, Black Beauty, gave me a list of photographers to visit. If the photographers liked your look, they would take your picture and use it in their portfolios. It was an exchange. Other models did the same thing. We’d go to a cheap store, buy clothes, take photographs in them, and then return them. That was how we did things. Mainly I loved going to different studios. There were about fifty. I met with James Moore and Arthur Elgort, who were top photographers then. I’d see Black photographers here and there, but none of them survived, even though they worked for Richard Avedon and Hiro. I used to go to dance studios too, like Henry LeTang. I loved visiting jewelry stores, shopping on Allen Street, and going to the Italian bodegas and pizza parlors on Carmine Street. New York building heights astonished me also—they were quite a sight to behold relative to the flatness of Columbus.

NV That paints a beautiful picture and comes into step with your own curiosities. Tell me about Kamoinge—what’s your favorite memory of the group?

MS I was on a go-see and heard two photographers talking. They debated whether photography was an art form or an artifact of nostalgia and finally agreed that it wasn’t nostalgia. Once I was in Kamoinge, I learned about photography as an art form. It was profound for me. There was a language, a history, there was composition and tone, and they had favorite photographers. I took that information and went to do my own searching.

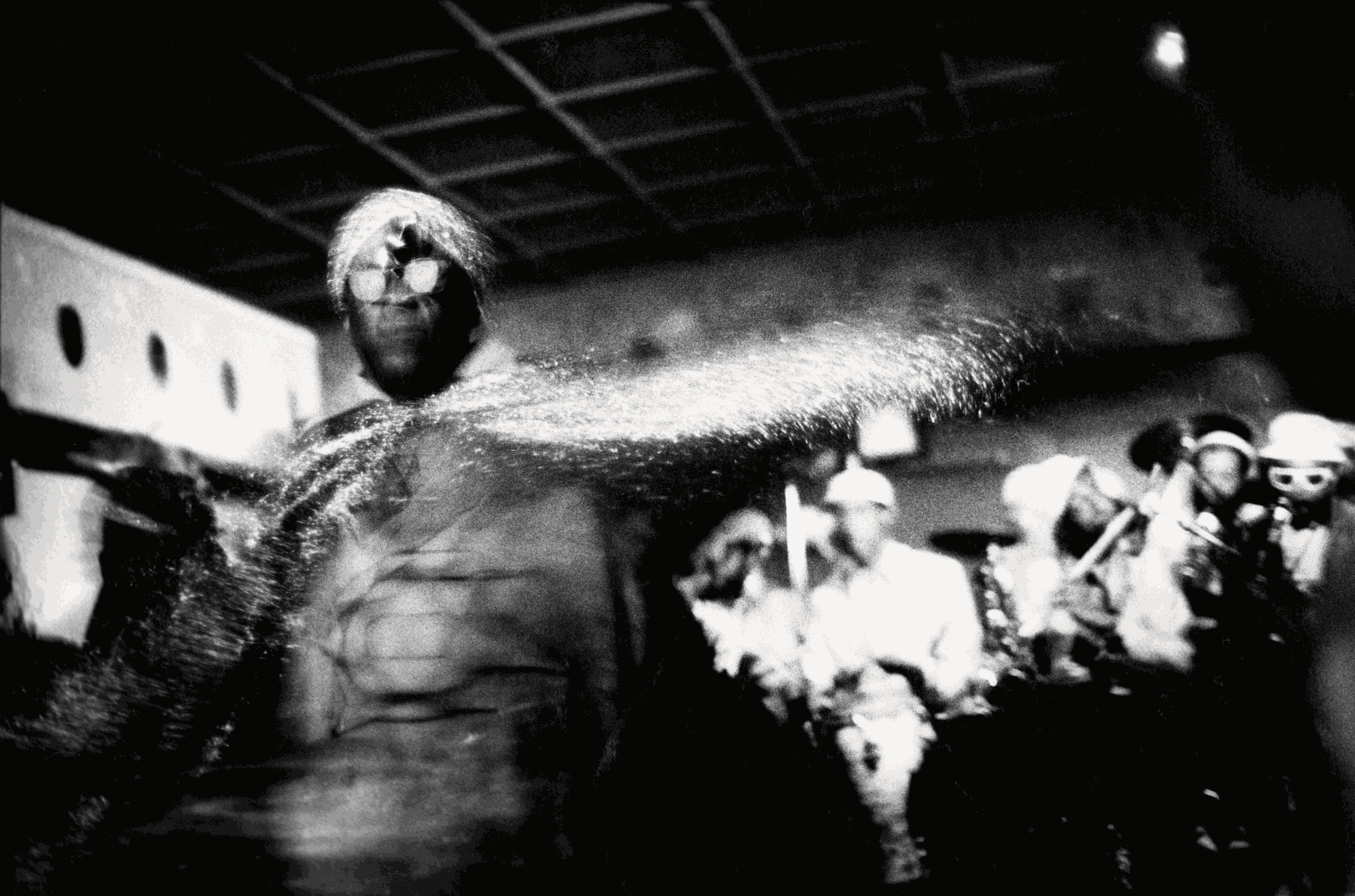

NV Arthur Jafa said in your recent Aperture monograph, “Ming’s capacity to control the dual technical strategies, the abnormality, of slow shutter speed and flattened tonal range—to erase the typical relationships between figure and background, foreground and background—are unparalleled.” This approach could be read as not only technical but scientific. Does your understanding of microbiology and microscopic organisms inform your photography?

MS That’s interesting. The most evident thing when observing microorganisms is balance. There’s movement too, but the real enchantment is harmony. It was beautiful to witness, regardless of the organism. When I was young, I liked leaves and looked at them obsessively. I could identify which trees they came from—oak, walnut, elm, or Juniperus pfitzeriana, a bush my grandfather had. My grandmother grew morning glories and I was fascinated by them. I must have been four or five and would wake up early to see them in full bloom; then at sunset, like clockwork, they’d close. It was unbelievable. In microbiology I experienced a deeper layer of that movement and balance, it was shockingly visual. When I photograph, I use that sense of harmony to find what looks good in the lens. I go where my instincts lead me and it either works or it doesn’t.

NV Staying on the topic of harmony, I’ve heard you say that you photograph like a painter and use light to paint. How so?

MS I’m aware of how things look in light, but it all happens in one moment. That’s the gift, the photographer’s talent: the capacity to compose by following one’s instincts. Also, the power of anticipation and the patience to wait for what’s coming. It’s like a basketball player hitting three-pointers: practice, repeat, practice, repeat. You get better, and still you’ll miss a few. In photography, you have to nail it the moment it’s in the lens. Take the shot when you see it.

NV Music plays an important role in your work. Why is it so central to your practice?

MS I’ve always been deeply affected by music. For me, it’s the highest art form. I remember hearing Puccini’s La Bohème as a child and crying. I felt moved, and it somehow reflected what was going on in me. I saw a lot of pain up close. My youngest, closest sister had asthma and could barely breathe. It was upsetting, so opera always affected me. On the other hand, we weren’t supposed to listen to R&B music. My father thought it meant dancing, frivolity, and being fast. It was the music of love songs, so I’d want to think about love and being with boys, which was an absolute no. I used to sneak a transistor radio under my pillow and listen, because they had R&B only early in the morning and evening. Otherwise there was no Black music. When I work now, I listen to jazz, which makes me feel relaxed and uninhibited.

NV Your husband was a jazz musician and you were on the road a lot. Talk about that period.

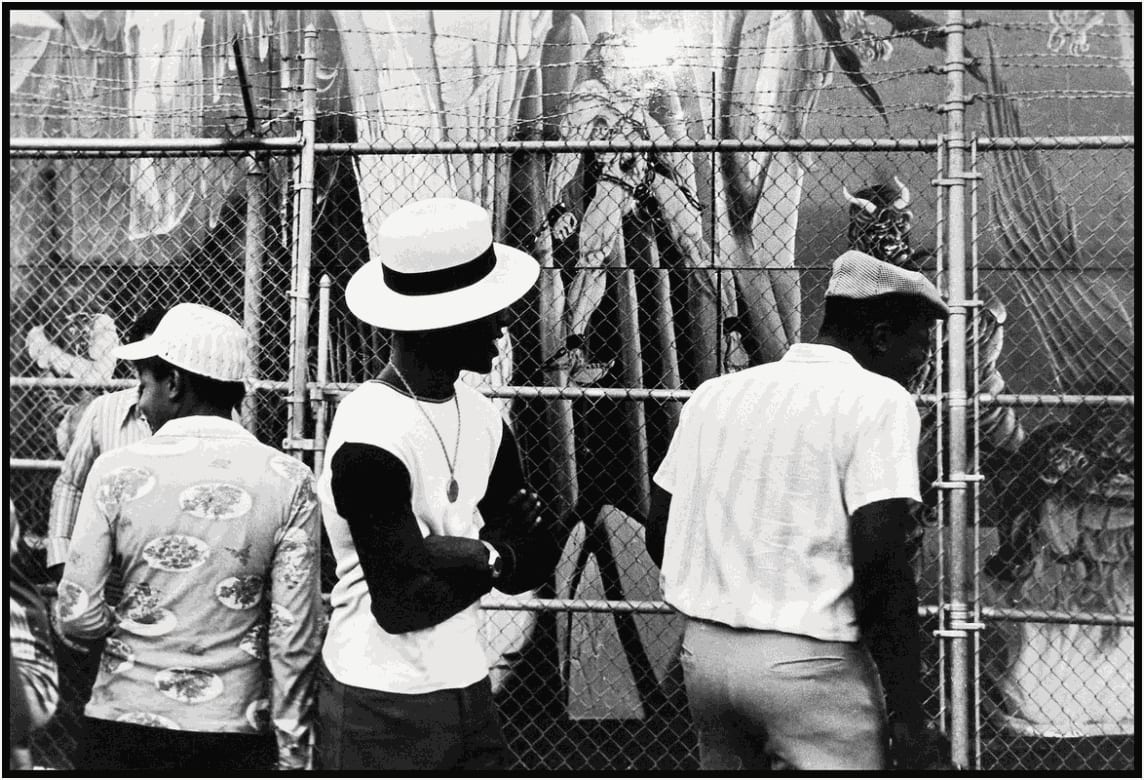

MS When I was on the road, I’d explore. It wasn’t only about the music; I’d take my son, Mingus, and my camera and head out while my ex was asleep. I immersed myself in the sights and sounds and realized people lived differently outside the United States. They related to jazz based on their own cultural frameworks. Like the three boys I shot in Portugal, in Ever-So-Hip-Kiddies, Setúbal, Portugal, 1979. They had cigarettes and soda and carried on like Dexter Gordon. But they were only seven years old! They thought it was cool to pretend because they were listening to jazz. I learned about the world and came to understand what the music meant to different people in different places.

NV What is your favorite jazz album of all time?

MSI like Miles Davis’s “Flamenco Sketches” [1959]. I play it all the time. Also Alice Coltrane’s Reflection on Creation and Space [1973].

NV Let’s talk about energy, which is central to your work. Energy is imperceptible and infinite yet subtle and surreal. How do you locate it? When do you know you’re holding court with something energetically worthy of capture?

MS You could call energy abstract, but it’s very obvious. It’s in everything, including the soul. Energy feeds you. When you look after yourself and the world and approach circumstance with a sense of care, you attract certain energies. The opposite is also true: when I photograph, the energy that I’m looking for finds me, not wholly do I find it. I suppose that’s synchronicity and photography is a two-way street. I feel very humble because for me, photography has been a spiritual journey and a calling. It presents itself and I’m a soldier in a cosmic army doing exactly what I’m supposed to do by taking that photograph. It’s my responsibility and not about ego at all. It’s really God’s work.

NV You’ve talked about Alice Coltrane’s going deep into silence. What do you think silence can teach us?

MS To listen. To listen to one’s self. Silence can bring you closer to the information you really need.

NV I know dance is one of your cardinal joys, we’ve done samba and sabar together. Those sessions are ceaseless in their instruction. There’s the physical phrase—the choreography, its interpretation, its performativity and repetition. Let’s talk about the relationship between photography and dance.

MS Katherine Dunham and her legacy brought me to dance. I started the technique in 1974, ’75, and didn’t stop dancing. Photography and dance are kindred because they both have rhythm and timing. Visually, there’s a way to paint space with body movement. It’s about lines and shapes. Like choreography, a photograph makes your intentions clear. Dance is a moving picture.

NV Besides Dunham, which other artists inspire you?

MS There are many, but I love Brassaï. He’s my favorite. Imogen Cunningham was wonderful, she was Diane Arbus’s teacher. I loved her as a person, though I didn’t know her work very well. We both lived in the Village and would eat at cheap Greek diners with her husband. We talked about life and love and she’d bring up “Dee-on, Dee-on.” I didn’t realize that Diane Arbus was “Dee-on” until someone said, “You pronounce her name Dee-on.” I thought, “Oh boy, Imogen and Lisette Model have been talking about Diane Arbus all this time!” Romare Bearden will always be a top pick, also Gordon Parks and his great essays for Life. Another genius is André Kertész. Then there’s Eugene Smith, whose photographs I adore. Also the sculptor Elizabeth Catlett.

NV In the ’30s, Henry Miller called Brassaï the “eye of Paris.” You too chronicle the mood of your complicated city. What draws you to his work?

MS I have to tell you a story first. After Brassaï passed, I went to see Henry & June [1990], a movie about Henry Miller. As I watched, I thought “This seems so familiar”—not just the storyline but the visuals. I realized that what I was watching was Brassaï’s photographs reenacted as moving images—it was stunning. I’m fascinated by the connection between artists and what they leave behind as legacy. I hope something similar happens with my work: maybe an artist will see a connection between me and another artist, then create something bigger than the two of us.

NV Your photograph of Brassaï really resounds. What was it like to take his picture?

MS J. Fredrick Smith had a show of his on 57th Street and it was a big deal. Brassaï himself was going to be there. I walked up and asked if I could take his photograph. He said yes. There was an umbrella nearby and he tried to help me by putting it in the frame. He moved it around because he wanted me to make a good picture. I understood what he was doing and will never forget it. One thing I notice about older photographers, which was true of Brassaï, is how much larger one eye becomes. Their eyes take on quite a personality. It must be the evolution of the tool.

NV I want to talk about August Moon [1991], the series of photographs you developed as an homage to the great American playwright August Wilson.

MS August Wilson’s characters are the famous and the not so famous. The people at the heart of Black community. Many of his stories resonate with me because I grew up in a similar body politic. A great many of those monologues and characters touched me—like Aunt Ester [in Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean, 2003], the mystic who is basically the personification of progress, rooted in an Afro-centric rather than Euro-centric past. I got on a Greyhound bus to Pittsburgh’s Hill District and took photographs with his characters in mind. I found the pool players, the dishwasher, the waitress at Memphis Lee’s diner, the barbershop, the steel mill, and his dreaming place. I just wanted the feeling of Black folks as a truly American experience. August Wilson used words and I used photographs.

NV What’s the single best piece of advice you’ve ever received as an artist and would give to one?

MS Don’t use someone else’s work to judge your own. Be honest and project your authentic self.