A siren wails in the distance, slicing open the afternoon silence. As her daughter takes her coat, the mother wonders if it is a good omen to hear sirens so soon after stepping into the house. On the way here, with her son driving and her daughter riding shotgun, she’d marvelled at her good fortune. For too long in her life, she’d worried that none of them would make it out of her marriage alive. Now look at her. Most importantly, look at her children all these years later, gifting her a house to celebrate her birthday.

She’d become obsessed with signs and omens during her marriage. It had been comforting to believe in some order to the universe beyond her husband’s rage. Even after she left him, she did not stop wondering how the things her children often dismissed as random connections might foretell her future.

Sirens always remind her of the country she still considers home two decades after she ran away from it with her children. Her father was a surgeon and until she got married she’d lived with her parents in a house that was close to the hospital where he worked. Hours on that street were punctuated with the sound of sirens as ambulances raced to and from the hospital.

When she moved here, hearing a siren was a good omen. It was as though her ancestors were reminding her that she carried them and her country within her. These days though, the sound is tainted. Now, she also thinks about the police and all those videos she’s watched on her phone. She thinks of the dead and dying young men who remind her too much of the son she still calls Little One though he is almost thirty. She lives in fear that someday soon, the face in one of those videos might be his.

“Do you remember the hospital back home?” She steps further into the room. Her daughter nods but her son shakes his head. He’s brought two bottles of wine and some wine glasses so they can celebrate. “Red or white Mama?” “Red, thank you. We used to hear sirens every time we visited your grandparents.”

He shakes his head, arranges the wine glasses on the coffee table and begins pouring the wine. “There was a hospital? Martha, white for you, right?”

“Yes, please. Mama had to take you there so many times with all the trouble you used to get yourself into. You liked to play with knives and blades. Anything sharp that could hurt you was always your favourite thing.”

“Not sure that has changed.” Little One laughs as he begins filling a second glass. “So, Mama, what do you think so far?”

“Let her see the other rooms first.” Martha says.

The mother sits in a chair and looks around the living room. Martha must have chosen the tiles on the floor. The mix of crimson with vermilion lines is just like it had been in her parents’ house. She kicks off her shoes. The cool tiles beneath her stockinged feet might be the closest she’ll get to home soil again.

“If this is all there is, it is already more than enough,” she says to her children.

“Are you happy?” Little One asks.

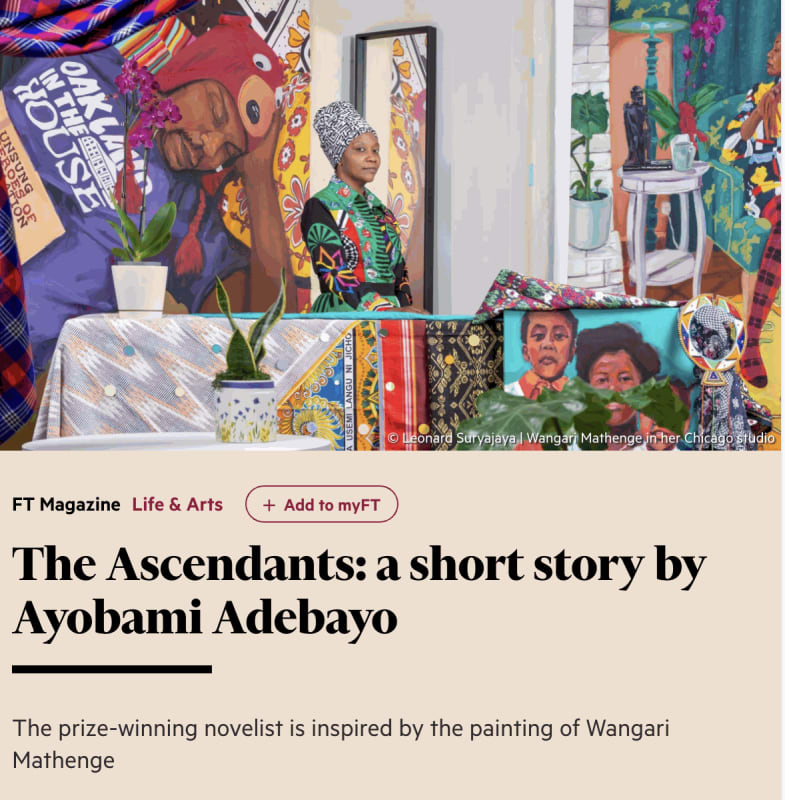

Wasn’t happiness a series of trade offs? Giving up one country for another that might never see your son as anything but a threat could mean keeping that son alive. Even if he has forgotten everything that once mattered to you. At least your daughter remembers home and even honours the ancestors. She must have picked the statuette that sits atop a book on the side stool. Only Martha would remember the Akamba curio, only she would care to use Khanga prints as accent pieces. The mother smiles. These, more than any siren sound, are the signs that she is finally at the crest of the mountain she’s been climbing. She had been outraged when Martha chose to study art history instead of law, but now she thinks she understands her daughter. Maybe her work in the museum is how she stays close to the home she’d known until she was ten. Happiness is a dozen contradictions held in the balance, if only for a moment.

“I am.” The mother says to her children with a smile. “I am.”

The siren is more insistent as it gets closer.

Like his mother, he prefers red wine to white. He pours himself a glass and sets it on the coffee table. He figures his mother might want to say a prayer before they clink glasses to toast the new place. Or want to continue reminiscing about the country she still calls home. He’s asked that they go back and visit more than three times now but she always responds with something like terror. Did he not read the news? Things were terrible back home right now; it was better to wait until the country settled down a little. Recently, her reasons for not going back have consisted of forwarded stories from the various groups she belongs to on WhatsApp. She does not care that he can never verify them. If her cousin thrice removed said people were being kidnapped in the arrival wing of the airport, it had to be true.

“I had a wrapper just like this rug. I liked it so much.” She says now, running a stockinged foot over the centre rug Martha had chosen. “It was a gift from my grandmother.”

Martha grins at him then sticks out her tongue. They had argued for a while about the decor. He wanted to get pieces from a local antiques store, but Martha was convinced that the items she’d chosen would delight their mother. If he’s honest, he’s not that interested in the decor. What bothers him is how Martha seems to know their mother in a way that often feels inaccessible to him. Martha’s memories from the old country are sharper. She speaks the language well enough that she was able to join discussions with their uncles and aunts while he often sat listening, trying to take apart each sentence to understand what was being said. He did not know many words besides the most basic greetings. Sometimes, he felt he was standing outside of his own family, alien from the language they probably dreamt in. Maybe he’d resisted the accent pieces because he wanted to prove to Martha that he knew their mother well too. As a compromise, they’d decided she would only decorate the living room before their mother got to see the house.

“A toast?” He lifts his glass.

“Let’s show her the other rooms first, then we’ll toast.” Martha shakes out her dress.

He helps his mother out of the chair and holds her as they follow Martha out of the living room. They’d decided on four bedrooms. One bedroom for their mother, another for Martha, who would be moving in with her and commuting to work. One room would be reserved for when he visited, and the fourth room would no doubt be occupied within days by some relative, close or distant, who had just arrived from the home country and needed a place to stay. If they were lucky, it would be just one person. Their mother had once taken in a family of five when they lived in a cramped two bedroom apartment.

“I love it,” his mother says when they get to the biggest bedroom. She lets go of his arm and points to the skylight. “I will see the stars at night.”

“Just like in your country?”

“It is your country too.” His mother sucks her teeth. “We didn’t have a skylight there. We lived in a block of flats.”

“I mean when you were younger, maybe in your village.”

“I’ve never been in a village.”

He walks away from her to examine a statuette on a dresser that came with the property. Martha has dotted the house with several African pieces like this one. Mostly wooden and metallic statuettes, a few small enough to fit in his palm. This one is probably the biggest. It is the gold-toned bust of a crowned, bejewelled woman. Definitely some imitation from the museum’s gift shop. He can’t tell where it is from, but it looks more west than east African to him. He’s looked at enough art from his mother’s country to know it isn’t from there.

“Which country is this from Martha?” He picks up the statuette and is surprised by its heft. It is not some hollowed out thing, it is much heavier than he’d anticipated.

His mother peers at it and shakes her head. “This is not from our place.”

“Martha?” He looks around and sees her standing by a window that opens into the street. “Martha?” “What?” She keeps looking into the street.

“Where is this from?''

She glances towards him, then whips around. “What do you mean? It’s from the museum’s gift shop, where else would I have gotten it?”

“I meant which country.” “It’s just an imitation.” She snatches it from him and puts it back on the dresser. “It could have been made anywhere.”

“Why are you shouting, Martha? Your brother is asking a simple question.” “Sorry, I’m just so hungry. Let’s toast the house and go out for lunch. I think there’s a pizza place down the street, we can even walk there.”

He watches with a frown as Martha hurries into the corridor without waiting for a reply.

The siren is louder than ever, its sound fills the house. Then suddenly, it becomes silent.

Martha goes to the kitchen. She is in front of the fridge before she remembers that it is still empty. She needs a beer. That would calm her before she joins her family in the living room. Standing by the window, she notices that the police car has parked in front of the building.

The two policemen in the car are staring at the house.

She started stealing from the museum two years ago, when she and her brother decided to gift their mother a house for her 60th birthday. Even then she knew that she would not be able to contribute any significant amount towards a down payment. She just did not earn that much. So, she’d thought of selling some art on the black m arket. At first, she only took little wooden pieces she could fit into her handbag, then she went for the bronzes before becoming bold enough to tuck a gold statuette in her backpack. She only took African art from a series of expeditions in the 1700s. The items had been neglected in the museum’s dusty basement and only a few had ever been displayed. Is she a thief if she was taking what had been stolen in the first place? Besides, she has not sold any of the statuettes. She has decided to keep them; some will adorn this house while she thinks about what to do with the others.

Martha goes to the sink. She turns on the tap, shuts her eyes and listens to the sound of rushing water. Once she feels calmer, she turns off the tap and goes to join her family.

“Are you all right, Martha?” Her brother asks as she settles on the sofa beside him.

She nods because she’s worried that her voice might tremble if she speaks.

“Before we make a toast, I want to thank both of you. You know, I did not imagine that I would ever own my own home in this country.” Their mother leans forward in her chair and clasps her hands together. “I just knew you two would have a better life here and this gift, both of you putting money together to buy this? It shows me you appreciate the sacrifices I’ve made over the years. Thank you, thank you so much.” She holds out her arms.

Martha watches her brother step into their mother’s embrace. He paid for the house but is generous enough to include her as part of the gift giving. Martha is sure their mother will never know that her main contribution is the decor, even the furniture has been paid for by her little brother. He followed the immigrant rule book and chose a sensible profession. Now, he works for a multinational law firm, travels to some new country every other week and probably earns more in an hour than she does in a month. Everyone is proud.

“Do you like the decor?” Martha asks. “So far at least, we’ll do the rooms together.”

A letter had been written recently to the museum’s director about repatriating some of the African pieces in its collection. Martha had been asked to draft a statement about how the museum was committed to preserving the pieces in perfect condition in order to introduce the world to the brilliance of black and African art.

“Those little little pieces of art here and there. The statuettes? Martha, they all make this place feel like home. Especially that Akamba one.”

Martha smiles. It is the only one that did not come from the museum. She’d emailed a cousin to buy one and ship it to her. Martha is sure the missing items will be discovered any day now, any decade now. Perhaps the discovery has already been made and the police are here for her. She’d changed her home address on the museum’s database once her brother signed the mortgage deed.

“We should buy another bottle of wine when we go out.” Her brother says. “And toast when we are back from the restaurant.” “No, why should we waste these ones? Little One, stop being extravagant, I’m telling you.” Their mother picks up her glass.

Her brother rolls his eyes and picks up his glass. They all drink to peace in their old country and prosperity in the new one, then they put on their coats and leave the house. Outside, in the driveway of the next-door house, two policemen chat with a woman who is still in her bathrobe.

“We should say hello to some neighbours,” their mother says. “Not now,” Martha says, quickening her pace. “I’ll bake something once we’ve moved in fully. Then we will go from door to door.”

Her brother puts his arm around her shoulder. “Send me some?” “If you’re in the country.”

They walk on in silence. Their mother stops occasionally to look around the neighbourhood and smile. Her brother keeps his hand on her shoulder. When the police car drives by, Martha reaches out and grips her mother’s hand.