As she prepared for her first solo UK show, at the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, Heisch spoke of how these new works are very much summer paintings, with the colours used to radiate energy, exuberance and motivation

The painter Angela Heisch (b1989, Auckland, New Zealand) is among a rising generation of American artists, including Amie Cunat, Matt Kleberg and Alice Tippit, who use the language of abstraction to explore personal experience within a shallow, stage-like space. Heisch’s paintings toe the line between personification and abstraction, their fields of colour delineated by razor-sharp edges cohering into compositions that seem to wink at the viewer. Following a recent series of solo exhibitions in New York, at 106 Green and the Davidson Gallery, the artist is preparing for her first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom, at the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, entitled Burgeon and Remain.

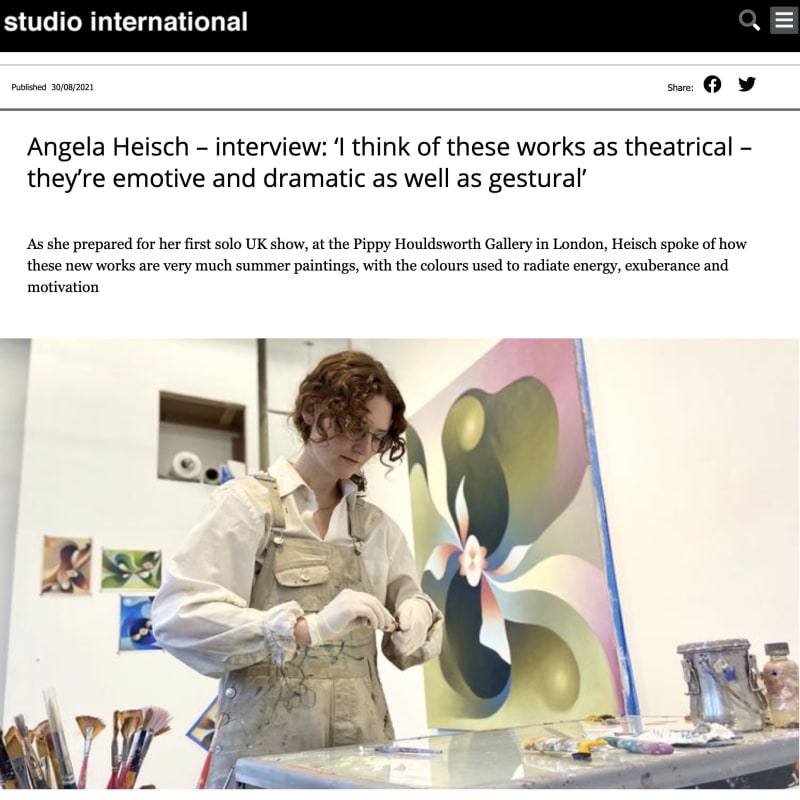

In advance of the exhibition, Studio International sat down with Heisch in her studio in the Bed-Stuy neighbourhood of Brooklyn.

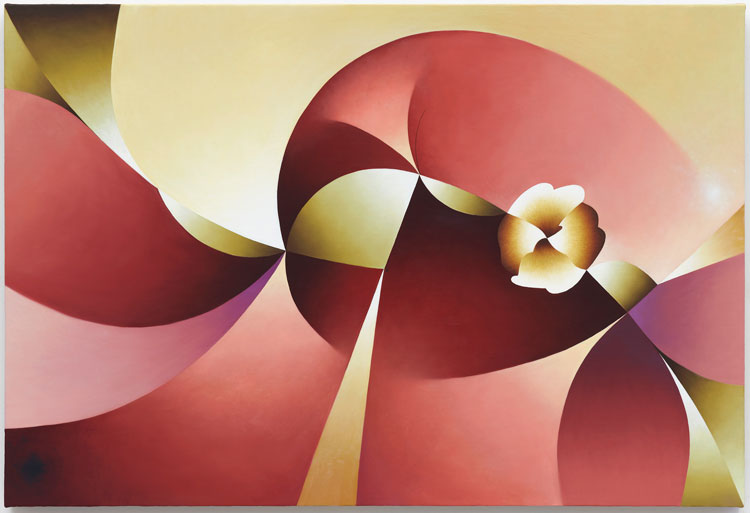

Elizabeth Buhe: Our conversation precedes your upcoming show at the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, your first solo show in the UK. There are 10 paintings, six larger and four smaller, as well as three pastel drawings. The colours are bright – lime greens, royal purples, velvety reds, golden yellows – and these sometimes change quickly in beautifully blended fields of colour. I’m looking, for instance, at the Agnes Pelton-like palette of Diving for Pearls (2021), in which pale yellow shades into blush and then into periwinkle. This variety of colour, especially in a single canvas like Flares (2021), is a departure from the primarily umber and blue tones of your most recent one-person exhibition at the Davidson Gallery in autumn 2020. How are you thinking about colour in these new canvases?

Angela Heisch: In the Davidson show, with all those umbers and blue tones, those paintings were referencing skyscapes, landscapes and figures. I was coming from this really limited place in terms of that colour palette. I wanted these most recent paintings in Burgeon and Remain to feel limitless in their colour: really juicy, ripe, boundless, representing energetic growth. I have a hard time talking about the current work without referencing where I’m coming from. I’ve typically worked with variations on complementary pairings and exploring the places in between. In this new work, I wanted colour to represent less the kind of growth that we see in nature or in physical reality, but something that exudes energy, exuberance and motivation. So, the colours in these paintings are a little less predictable in that way.

EB: Your idea of ripeness makes me think of the way Renaissance art dealt with cycles of the seasons, like the abundance of Arcimboldo’s portraits or Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s late summer harvesters at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. You share with both painters a precisionism in the application of paint, too. Are yours “summer” paintings? Do they have a temporality, or the kind of cyclical logic we might ascribe to the unfolding of the seasons? Of course, you moved into this work based on what came before, but is there a way in which it had to have been made in the last eight or nine months – over the spring and summer, or during the pandemic?

AH: Yeah. These are definitely summer paintings to me, but I just happened to finish this body of work in the height of summer, or towards the end of summer. I started on it in February, but I was very much thinking of that fully realised growth cycle and that momentary period of stillness before decay. This is the peak; this is as alive as these forms will ever be. Over this past year, I’ve made two shows referencing the seasons, the other one being Springs at Projet Pangée in Montreal, which were landscapes, where I was thinking more of new growth. I didn’t consciously set out to make two bodies of work referencing specific seasons, but it’s where my mind has been, especially over the past year. I didn’t want to make work solely about quarantine or Covid or politics, but rather the things that we can rely on. I’ve found comfort in that repetition and those unfailing patterns. In this work, while referencing these patterns in nature, I’m thinking of pattern as a rhythmic structure: the patterns of the seasons, their dependability, like the changing of the seasons or the beginning of a new day. These paintings are a place to feel OK with multiple interpretations, or without completing a certain narrative. Here, uncertainty is a positive thing.

EB: It is so interesting that the reliability of patterns in nature is a way you understand the work to relate the situation of the pandemic, without being about the pandemic per se. It’s an intermediary term, abstracted from the reality of personal experience.

AH: Right. We can depend on artists making work about Covid, just like we can almost depend on Covid not going away. But we can also depend on positive recurrences, and feel at ease, if only momentarily.

EB: Do you look at Books of Hours or medieval calendars?

AH: No, I don’t, but I will. But I really loved your reference to Arcimboldo. I’ve always loved those portraits, but I have never drawn that parallel. Of course, his paintings are more literal in their reference to life and inevitable decay, and they feel a little more sinister than my most recent work. I’m drawing the connection more with the reference to life forms in their prime, that are ephemeral. There’s also that returned gaze, but with a stillness and kind of emptiness at the same time. I really relate to those features in his work.

EB: Thinking about the cycles of the seasons makes me wonder how the paintings relate to each other. They will be shown together in London. Do they relate spatially, like puzzle pieces that fit together, or temporally, like snapshots of a scene that alters over time? Can we imagine that they communicate with each other invisibly through form, maybe through their arcing lines, like trees do through their roots?

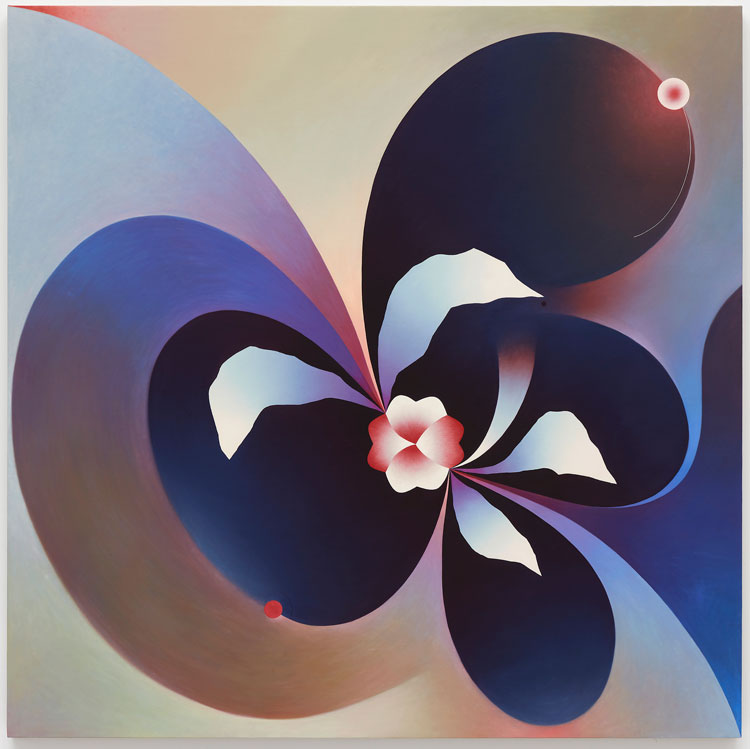

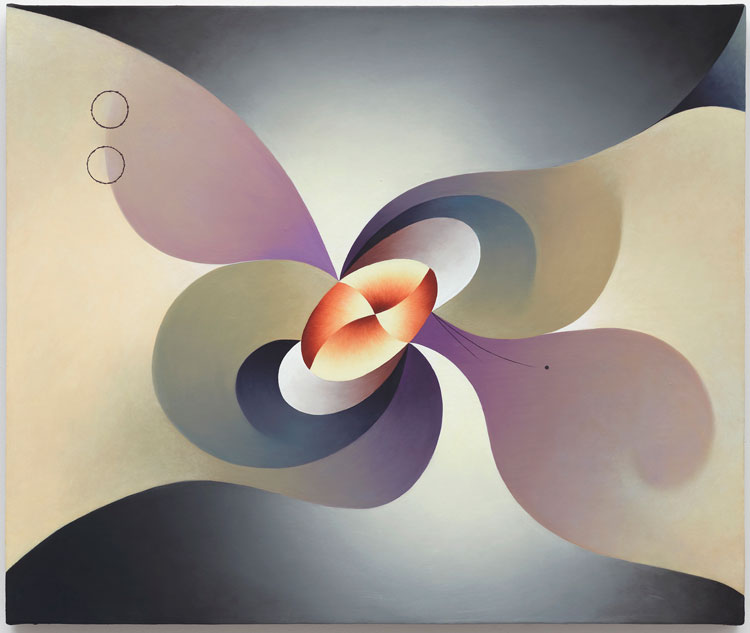

AH: I think when the show is installed, the works will productively be in conversation with one another and referencing one another, since they are using the same language. There are repeated motifs and symbols. For example, one that I’m going to call that spinning disk or floral motif, that usually acts as the origin of the painting. I’m thinking of all these different elements as made from the same material or cut from the same cloth, so they might act similarly in their different environments. In some of the paintings, that disk or floral motif is whole, while in others it’s starting to separate, like cells dividing under a microscope. In another painting, it’s spinning or tearing. There are also the repeated gradated fragments. They’re like pieces of a whole. Sometimes they might look like shards of light. Other times they reference leaves or celestial bodies. These forms have many different iterations, so there is a sense of narrative or evolution within the language. I love the idea of them conversing with, and being aware of, one another, like trees. I was just listening to [the author] Michael Pollan talk about trees and how, through their roots, but also through their leaves, they communicate, and I love that thought. However, these paintings are very much defined by their perimeters. I am thinking of the elements in each painting as reacting to their own specific environments that are created with colour fields that evoke certain densities, atmospheres, a playfulness or heaviness.

EB: In terms of reacting to the container, is there a distinction for you between the process of making, in which there’s a certain amount of available space in which you can paint, and the process of interpretation once the painting is finished, in which we read these shapes as hemmed in within their own world?

AH: I don’t know if there’s a difference there. It is very much about the process because the process is really intuitive. I’ve been leaning into that aspect of the work: that each form in the painting is reacting to the one before it. However, they are structured. It’s not like they’re totally intuitive. There’s always some kind of spine or central point that everything unravels from, grows from, hangs from or is balancing on. Through that process they grow outwards and are very limited by their space.

EB: When you described how the paintings are in conversation with each other, you used the word shard. Your language seemed more mechanical than natural or biological. That made me think of Heavy Metal, and I wonder if you could talk about its two little circles, which look like gears.

AH: I’m trying to play with line quality. There are those little wisps of hair that have a very fine pen line quality. That painting felt a little precarious, a little unnerving. There are always two “eyes”, at least, in each painting, but in Heavy Metal I wanted those two eyes to be nonsensically stacked on top of one another. I was thinking of barbed wire or a thorny branch, creating these fragile and hollow shapes that feel unnerving or a bit dangerous. This particular painting, similar to my older work, felt a little threatening, set in stone, less playful, less interactive.

EB: We have been talking about the realms of experience the paintings evoke, and one thing I find so compelling is that they achieve a level of specificity without pointing to any specific referent. They imply the vegetal, but also the celestial. It is astonishing that they could be equally about earth and sky, microscopic and macroscopic. Your titles, though, push us toward the tangible realm: In the Grass, Rose Bush, Grassy Landscape. Where are we, more or less, in your paintings?

AH: It might sound cheesy, but I want you to be everywhere in these paintings. I want them to place you in multiple dimensions. They’re meant to be vague and associative and, importantly, familiar. They’re not explicitly referencing that tree over there, or that sky, but I am drawing from the collective world around me. That being said, I don’t want the paintings to feel tethered to the rules of logic. Like, this is how a space recedes, or this is how a light source hits an object. I want each painting to contain multitudes, in the sense of where it places you. They may feel tightly packed in the ground or floating in space. The work may place you in a very specific memory, or you may remain present in your experience with painting and its objective offerings. They may evoke multiple perspectives as well, and I’m OK with that. In that sense, these paintings feel generous, or at least I hope they do. The titles are more about an emotive response that I have to the work when it’s finished. Rose Bush, for example, is similar to Heavy Metal in its precariousness. Rose Bush feels alluring and is inviting you to go up and touch it, but it wouldn’t be that simple. It feels strong in its colour but fragile and wild in its architecture. I was thinking of that allure and those loops of thorns you sometimes see in roses growing up a trellis. That imagery feels similar to the curved spine of the painting, with spurts of light attached, reminiscent of thorns. Rose Bush is a descriptor for the sensory response I was having to all these components at play within the painting.

EB: This brings me to something I often wonder while in front of your work, which concerns the paintings’ spatial operations. Are we in a three-dimensional world-like space, an imagined or dream-like space with its own rules and gravity, or on a flat surface? I see these works as related to the sensory environments of Helen Torr and Arthur Dove as well as to the hard-edged landscapes of precisionists such as Charles Sheeler, even if landscape isn’t the right word. Are those whiplash lines in Flares hooks, waves, and tendrils; do they project back into a deep space, like an orbit or halo seen obliquely? But I can also see the eerie surrealistic vistas of Leonora Carrington or Maureen St Vincent, in which space is maybe no less real than in early American modernism. In both those scenarios there is a kind of receding depicted space, but your shapes also seem to react to one another on a flat plane, like oil droplets floating on the surface of a puddle. How do you understand the space of these paintings? Or would you rather leave it open to multiple possibilities?

AH: The space is not very deep, but that doesn’t mean the space isn’t there. It’s in keeping with that vagueness, like withholding some of the information. I tend to think of the space in my paintings as a stage, so that is where that shallow space is coming from, but it’s a space you can enter. I also think of these works as theatrical, in the sense that they’re emotive and dramatic as well as gestural. When I’m thinking about that stage space, I’m thinking about it as a confrontation or presentation, revealing itself to the viewer.

EB: Is that related to your interest in Paul Klee?

AH: Yeah, I do think of Klee’s works in that sense. I think of his works as really theatrical. He was the first painter I looked at when I started working abstractly. I started abstractly with linear drawings, and his idea that “drawing is like taking a line for a walk” really spoke to me. That personification and whimsy is really related to the way I think about abstraction. His work has such a broad range, it’s so associative and emotive, but there’s also that stage-like space that makes them feel really theatrical. This is similar to the way I identify with Dove, although his work feels more solitary than Klee’s. Similar to how I often approach space and composition, Dove presents these solemn figures in a vague but moody space. He often defines space through echoing forms or circles, creating that shallow, withholding space.

EB: Thinking of Torr and Dove, is there something multisensory in the work, like the materialisation of sound? You and Dove do both have paintings titled Foghorns.

AH: I was thinking about Dove’s Foghorns when I made my Foghorns piece, yes. This isn’t explicitly about sound, but I was thinking more about reverberation, some kind of vibration or echo. I wanted colour and line to echo to create a dynamism and movement outward. Less about sound; although I see how reverberation can be sound. It doesn’t have to be. There is a rhythm to the compositions through the interaction of the lines with one another, the repeated swelling of forms. That can be musical, but I think of it as more rhythmic in terms of space.

EB: Is it through rhythm or repetition that the works are personified? Or is it through your comma- or eye-like marks?

AH: It’s more so through the marks you mentioned. In these works, the personification is often through gestures. These aren’t explicitly figures, but I am thinking of how the painting is presenting itself. So, there’s personification there; giving the painting some kind of authority. Is it welcoming and inviting? Is it relaxed and reclined? In Aware of the Puddle (2021), the gesture is of bending over, of gazing down at something. In Deep Climb (2021), there are elements in the painting that are clinging on to and moving up a curved spine. There are features that feel more figurative or personified, like eyelashes or wisps of hair. In Deep Climb, there’s a grey swoosh of hair. I really like playing with those associations. These paintings contain eyes and a gaze, but the eyes are less explicit than in previous works.

EB: We are moving toward personification in the paintings, which is a kind of generosity, as you have said. Can you elaborate on the freedom of interpretation that you grant the viewer? When we last spoke, you mentioned The Object Stares Back by James Elkins.

AH: The Object Stares Back. Yes. I related very much to some of the things written in that book. One quote I love is: “Objects look back, and their incoming gaze tells me what I am.” This is such an important function of abstract art, and why I struggled to find the words to talk about my work for so long. That struggle was coming from a place of not wanting my work to be so personal to me and my experience, while wanting to give people answers as to what they were looking at. Abstract paintings function as mirrors and, in that way, the paintings offer a great deal of freedom for the viewer to see what they will. I’ve always been drawn to that momentary registration of an object, before your brain makes sense of it, or places it with a name or category. It’s a moment before everything makes sense and you have all the answers. There’s that play there before logic sets in and tells you “That’s a lamp” or “That’s a snail”, and you move on. In this way, the paintings are always asking a question, and although they are generous, their gesture is an invitation to the viewer: what do you think of me? What do you make of me? How do you make sense of this?

EB: This relates to affect.

AH: Yeah, I’ve always had emotional responses to inanimate objects. Every time I boil hot water, as soon as the water is boiled, I like to take the pot off the hot surface because I feel like it needs to have a rest. I was just visiting my parents last summer and left a towel outside. Before going to sleep that night, I was worrying about it, laying alone on the grass in the dark. When we park our car and my husband doesn’t align the wheels, the car looks so unresolved. Out loud, I try to justify it as “not being good for the mechanics of the car”, but it’s really just so unsettling and looks uncomfortable, especially as a resting spot. I’ll stop before I sound too insane, but I think these inclinations are something that informs the paintings – wanting things to feel in their place, to embody that sense of resolution and that restfulness.

EB: It is about how we relate to non-human things. You mentioned Martin Johnson Heade in our last conversation. His orchid paintings are so easy to personify – we can imagine the flowers as actors in his landscapes. For you, how does personification point to narrative in your paintings? Do your paintings allude to stories, or are they closer to instantaneous glimpses of something?

AH: I’m not necessarily thinking of the narrative in the long term. I’m more thinking of a momentary, quick presentation. I think of forms within the work quickly arranging themselves to look presentable and offering themselves in some sort of cohesive way, whether it be through association or visual resolve. I love Heade’s jungly orchid and hummingbird paintings. There’s a sense maybe of a longer narrative within his work, but there’s also those quick interactions between birds, orchids and butterflies that feel more like glimpses of a momentary scene. Those paintings feel very playful and interactive in that way, with a sense of stillness, which is what I connected with.

EB: Have you seen much of his work in person?

AH: No, I haven’t. The Met has a hummingbird painting of his, Hummingbird and Passionflowers (1875-85). I have a beautiful book of his work that I got in the midst of lockdown last March, and his paintings felt like the perfect place to escape during that time.

EB: Talking about Heade makes me wonder what other artists have been important for you, historically and among your peers?

AH: You mentioned Leonora Carrington earlier, and I love her paintings and short stories. There’s a surrealist tendency that I carry in my practice related to the careful rendering of a painting, but the elements at play in the painting being a kind of nonsense. Maybe this is more evident in the work of Agnes Pelton or Maureen St Vincent. Each form in Maureen’s work contains multitudes, whether body parts or landscape. The same is true with Leonora Carrington; her stories are all about inanimate objects, such as chairs or rocking horses that come to life and have complex personalities. Georgio de Chirico, Joan Miró and Hilma af Klint are artists I’ve been looking at over the years. I love Donald Moffett’s wood and resin pieces. Alicia Adamerovich and Carl d’Alvia, in the sense that their language feels very much pulled from experiences or the physical realm, while getting at that element of nonsense, humour and play. Ginny Casey’s work is in a similar camp, in the way she explicitly personifies household objects and plant life, with that sense of play. I love Loie Hollowell’s work, and the resoluteness yet softness of her paintings. I love the recent work of Inka Essenhigh and Louise Bonnet. There are so many amazing artists to mention, but those are the ones I feel most closely aligned with.

EB: Let’s talk a little about process. How does your idea for painting begin? You are also exhibiting pastel drawings at Pippy Houldsworth; what is the role of the pastel in your process?

AH: The paintings start with a series of thumbnails. These thumbnails come from observations, or something that just pops up in my head. Sometimes, I jot down scribbles in the “notes” app on my phone. I’ll start someplace like that and then hammer it out through maybe three to six thumbnail sketches that present different versions of one idea. If I plan to make a larger painting, I like to work out details in a pastel first. The pastels always feel like they’re in preparation for something larger because they fill up my field of vision when I’m working on them. They’re a great way to work out composition and colour and feel like a really sped-up version of oil painting in terms of the layering. All this being said, often a pastel is never made into a painting, but even then they act as an informative part of the process, in determining what not to paint.

EB: How long does it take you to make these different types of works?

AH: From start to finish, a pastel takes a day or two; maybe 16 hours. A small painting takes two or three weeks. The larger works take about a month, maybe more. I try to get all the big questions sorted out in a pastel before I start the larger paintings, otherwise I spend so much time going back and forth deciding colours and waiting for things to dry.

EB: You’re working on a prepared surface.

AH: I’m working on linen over panel, sanding them down relatively smooth with maybe five or six layers of gesso, sanded in between every layer. They’re smooth to the touch but not as smooth as the older works on muslin. I’m not looking for that paper-like smooth consistency either. We were talking about Julie Mehretu the other day and I just saw her work at the Whitney. Those are some crazy smooth surfaces! Those surfaces really lend themselves to her work, and I enjoyed gliding across the smooth muslin I used to work on, but since moving back to oil, I’ve been embracing a little inconsistency.

EB: How does a painting confront us differently based on its size?

AH: The smaller paintings have an intimacy to them, and often feel like a closeup of a larger picture, as in Cool Snip (2021) and Warmed Snip (2021). Regardless of size, I want you to feel inclined to get closer to the work. The bits of detail you mentioned above, the wispy hairs or beauty marks, these elements are really important in the work and give them a fragility and complexity. I always want there to be that interaction, and hope the viewer is inclined to look for those details in the work on closer inspection. The smaller works function a bit differently in that way, but similar to the larger works, are open to a kind of reciprocal conversation with the viewer.

Angela Heisch: Burgeon and Remain will be at the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London, from 3 September to 2 October 2021.