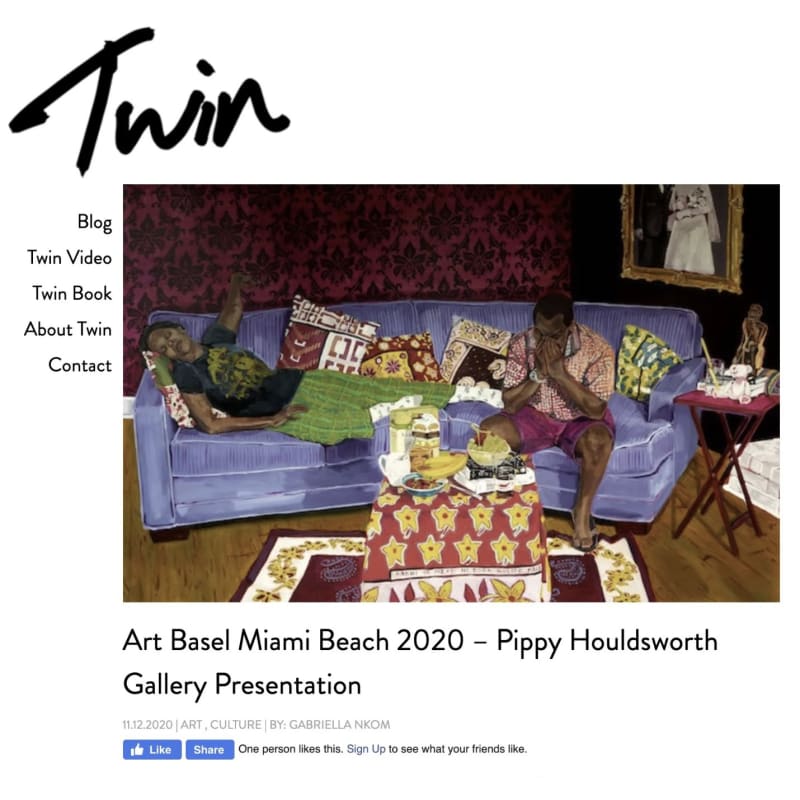

A celebration of thought provoking and eclectic work – this year’s Art Basel Miami Beach Exhibition introduces the work of artists across different generations. Presented by Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, this all-female exhibition brings together works that explore different subject matters and as captioned on the site “initiates a dialogue between feminist icons and the younger generation, reflecting the programme as a whole”.

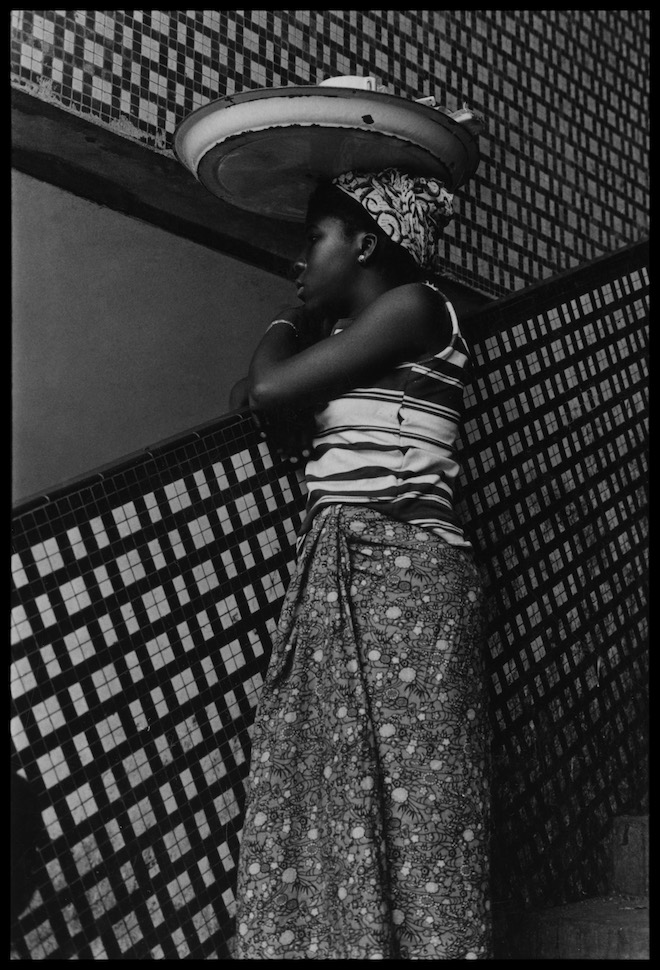

Although the presentation is usually held in person, the show will include ‘viewing rooms’, where the public can wander around in virtual rooms that showcase digitalised versions of each artist’s work. The line-up includes the likes of Mary Kelly, a staple figure in feminist art, Ming Smith’s street photography which focused its lens on African Americans in the 1970s, and work from Jacqueline de Jong who was an editor for the experimental platform The Situationist Times.

The talent does not stop there, with the inclusion of prolific work from the younger generation. Highlights from painters Jadé Fadojutimi and Stefanie Heinze, the vibrant portraiture of Wangari Mathenge, Zoë Buckman’s repurposed textiles and the hypnotic oil on linen pieces by Angela Heisch. These works were created specifically for the fair and offer a deep dive into each artist’s psyche – how they postulate change, their ideas on identity, and how their individual work connects to larger ideas.

In an exclusive interview, Zoë Buckman and Wangari Mathenge sat down with Twin Magazine and revealed some of their thoughts surrounding their work, the exhibition itself, and the ways they have continued to create during this turbulent time.

ZOË BUCKMAN

How does it feel to be a part of an all-female art exhibition?

I was so excited when I saw that. Also those artists, the ones Pippy has selected, I am just delighted to be in such esteemed company. I know and really admire Ming Smith, we’re kind of a part of the same community here in the art world in New York, and I have obviously been a long admirer of hers. But also for me, Mary Kelly is a big one too because I actually studied her work at school, and I have her books and she has been a massive inspiration to me as I have attempted to juggle being an artist but also a mother. I’m getting to know the other artists on Pippy’s programme and it’s exciting.

I have noticed that you use boxing gloves quite often in your work – why did you choose this medium for this piece and this exhibition?

I’m really interested in the space in between polarised states. And I think that conversation or that tension between the stereotypically masculine and the stereotypically feminine, has always been a really interesting terrain for me to make art from. I do box [and] for a particular time in my life it was very formative for me because it gave me a space to work through both feelings of frustration and anger about what was going on politically in the world at the time. This was in 2016 in the run-up to the general election here in the States. I just began to really feel that there was this mounting war on women against our rights, and our body, and our body autonomy. It was also when there was a lot being circulated about rape, and scoring different experiences of rape against each other. It was a time where I was finding my feet as an artist in the art world, which is a very male dominated arena. In a way the boxing gym gave me a space to work through certain personal traumas, but it also gave me practice at learning how to hold my own and take up space, and even take space away from others.

Visually boxing and iconography, like boxing gloves are very interesting to me because a lot of my work does look at masculinity, aggression and violence. So using boxing gloves but reworking them with these domestic feminine textiles, and often placing so that one is balancing on the other and bringing a kind of fragility to something that is stereotypically quite masculine and resilient.

The phrase “it stings” has also been used in your work prior. What does this statement mean in your work?

A lot of the texts that I use in my work, both the titles, for what I write and embroider, that is taken from this ongoing poem that I’m writing. The poem is called “show me your bruises then” and it weaves together snippets of conversations or memories, or things that women have said to me, or even things that men have said to me. A lot of the text is from my own experiences with relationships with men. But that particular line it used to be “it stings, I sob”, that was taken from a play my mother wrote about her experience [of] coming on her period for the first time.

In the Jewish tradition, the matriarch of the family will slap the young woman across the face the first time she gets her period. And so that was obviously this deeply problematic ritual for women, at least for my Mum she didn’t know what was happening to her body, and she didn’t know she was going to get slapped in the face by her grandmother. It’s this way of using a violent act to mark a significant time in a woman’s life. She found that, and therefore I find that really interesting and problematic.

I also merged that with another piece of text which said “Mama would use that cloth to cook and clean, and she would use that cloth to make a sling”. She was talking about her grandmother in the kitchen using these tea towels in all these different ways. When a kid broke his arm, she would use that cloth to make a sling, but she would also use that cloth to tend to her own black eye. This line “it stings” for me, I’m sort of looking at the feminist experience. You can apply that “it stings, I sob” to coming on you period the first time, to losing your virginity, to experiencing violence, to experiencing heartbreak: it just seems so universal to me.

As an artist and creator, do you believe your art has an obligation to tackle wider socio-political subjects?

I try to veer away from any feelings of obligation because I feel they can limit the creative process. But I was brought up with this example of art being something that is used to examine or attempt to change the status quo. I personally will always use my art to do that. I think it’s something that I just intuitively want to do, and do. But I don’t feel like I am obligated.

How does your art speak to your own experience as a woman and to the ‘female experience’ as a whole?

The series that I create they always start from a personal experience. Whether that’s divorce, grieving the loss of my mother, or sexual violence, or abortion or whatever is the impotence for me to embark on a series. It also comes from something within me that I find difficult or problematic or complicated. And then I go through a process of expanding that out and talking to other women, and bringing other women’s experiences and stories in the work. I hope it will always be something that is collective. For example, I’m not interested in making work that is solely about something that I have gone through. I’m more interested in saying “I have an experience with this” and I know there are plenty of women out there that have that; I want to share that space with them.

One of the subject matters highlighted in this exhibition is “metamorphosis”. Did you go through a process of change or metamorphosis that brought you to creating these two pieces?

I think that I’ve been on a real journey of transformation. The last few years for me have been almost a fast track of different experiences: from a divorce, to losing my mother to a terminal illness, to a very painful breakup from a relationship where there was violence and assault. A lot of that has brought a real complex darkness to my work as I have been exploring those things in my work. But more recently I feel that I am arriving at a place of joy and celebration. I think from my own spiritual practice, and through my relationships with other women, my best friends – my gyaldem, it has really put me in touch with this kind of inner force of creativity, and resilience, and joy. A lot of this work is looking at how we as women overcome the fuckeries that life throws at us. Through prayers, and devotion, and dancing, and raving and being together and through accessing our own ‘inner wild space’, and our own ‘inner wild women’; I think that is really the antidote to subjugation, and oppression, and trauma.

In the current tumultuous time we are living in right now, (Covid-19, the US election, police brutality), where does your work as an artist fit into these conversations?

I think that where the work explores as an antidote to oppression, and trauma and difficulty, choosing and seeking out joy, and connection to spirit and that inner wilderness that I was referencing; I think that sort of fits in with what is going on right now. Everybody is going through something, everybody is grieving something right now or everybody is anxious about something right now, or feeling trapped or limited or held back. Those are things I have had experience with, and some practice with. And so I think offering as a tool for those difficult experiences, this connection to something that is within us that can’t be limited, can’t be held back or trapped. I think that is a good way of reaching people during this time and what they’re going through.

Wangari Mathenge

I noticed that you use oil paints in the majority of your work. Why did you choose this medium specifically?

It started just out of curiosity. I actually started painting with watercolours and acrylic. I just used to look at artworks a lot, like when you go to museums [and] there was this quality, a sort of richness that I noticed. I noticed the difference between oils and acrylics. Acrylics have come a long way and they mimic oils right now, back in the day acrylics were kind of dry and they didn’t really have the mixing mediums that they have right now; I think you can mimic an oil painting with acrylics now. When I was doing it, you could tell the difference. And so it was really curiosity. The first time I ever tried to work with oils, it was a complete disaster. It was a very difficult material to understand. And then it just became a quest to understand the language of oils. And then after a while, I just became good at it I guess. Initially it was just curiosity, and now the reason I still paint with oil is – I think just being comfortable with it.

As an artist that has a diasporic experience, being between more than one culture, how does your artwork speak to your experiences?

For me I think it changes. Initially what ‘diaspora’ meant to me when I started painting and thinking about it is very different to what it means to me today. Initially I think it was more of a statement, and now it’s more of an exploration of ‘what is diaspora?’. I think that would happen in any time you’re trying to work out something, whether you’re writing or whether you’re painting it tends to become this exploration, this understanding. With my works what you’ll notice is the motifs and objects, and all of these sort of informs that inquisition which is “what is diaspora?”, because it means [something] different to any individual.

Most recently, I started reading this book ‘Potential History’ by Ariella Azoulay. It’s really interesting because it questions this whole notion of culture, objects, history, art history: what is it? I think for me, especially now with my work, I’m beginning to really look at what my place is in the world, my place in Chicago, the United States. How I have always kind of thought of myself as being a part from Kenya, and sort of being a part from here [United States], with a basis of being diasporic. But really what is that? I realised that there really is no understanding of what that culture looks like. And so [I’m] basically trying to explore that in my work.

Do you see your work as a direct representation of you as an individual and your identity?

Yeah. I think it has to be. It’s an interesting question, because I have never thought about it not being that I guess. So it must be.

How has the current world, this ‘new normal’ we are living in affected your work as a creative? Has it enhanced or hindered your work?

The thing is that I have been in school, right? Especially since Covid happened, the only thing that changed is that I was going to class and mingling with my peers and I had a studio on campus, and then we were relegated to distanced learning. Initially I had to change what I need, because I didn’t have access to the kind of space that I had in school.

In a way it also makes you a little bit more introspective, because when I was in school I had my colleagues, and I had my professors walking in and kind of making the paintings with me because they come in [and] make comments, and you adjust accordingly. While now because you don’t really have eyeballs on your work all the time it forces you to go I think a little more inwards and pull things out. I think for me the change has been a self-direction. I say it’s forced self-direction because part of being in school is that you’re looking for that direction, and you’re looking to be challenged in that way. But because of Covid that hasn’t quite happened in the last 5-6 months.

What do you hope this exhibition will do for you and your work as an artist moving forward?

I think I would love to have more people have conversations. And I guess the exhibition has more people seeing my work, right? Like you had said you hadn’t seen the work before and so having more people see the work and then engaging in the conversation is always helpful, because I’m not making this work just for me. So I would hope that all those conversations then helps the work grow and become something else as you move along.

What do you hope people will take away from your artistry? Is there a particular message that you want to portray?

No. Definitely for me I know what it is that I’m trying to get out of it. I would prefer to leave it a little bit open ended, rather than say that “Okay, this is what I am trying to convey”. I would rather leave it open ended because I think that’s how we live in any case. When we are confronted with visual things and even with writing, there isn’t that capability to always have the author or the artist translate what is going on. I would like for people to come to the work and take with it whatever they want to. And if it can do that, if it can relate to them in some way without me saying anything, then I guess that’s what I’m looking for.