Ming Smith is not a name familiar with most. A life led deeply underrepresented or recognised, the work of Ming Smith has been largely ignored in spite of her longtime dedication to the art of photography.

The first and for the most part the only female member of the Kamoinge Workshop – the African American photography collective dedicated to producing significant visual images of their time – the first black woman to have her work collected by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and an ardent photographer of black cultural figures, from the playwright August Wilson to Grace Jones to Nina Simone, Ming’s impact and works carry the spirit of the underrepresented black American experience.

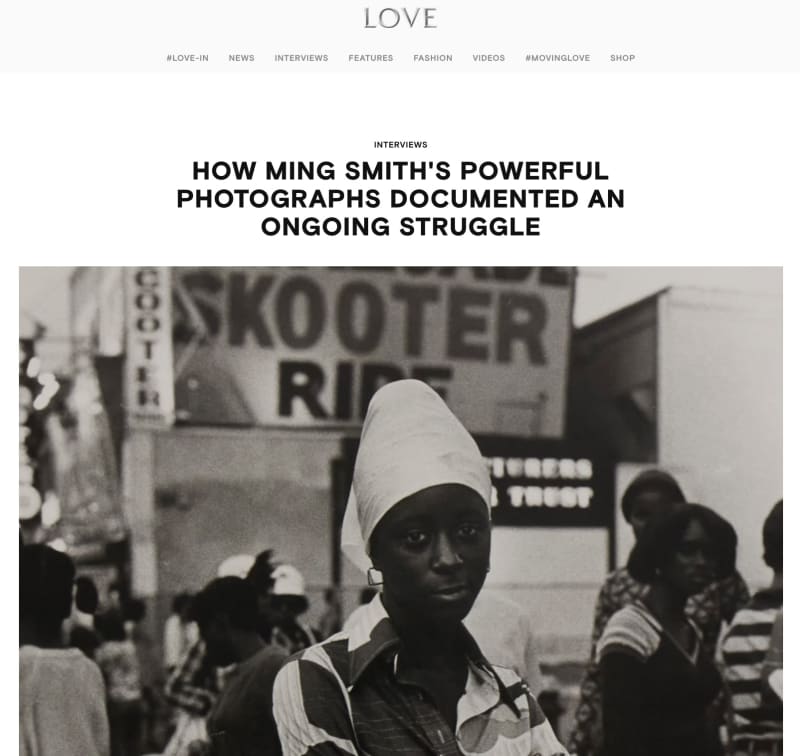

Showcasing a selection of her photographs namely from the 1970s, Pippy Houldsworth gallery in London is holding an exhibition of this deeply undervalued artist - luckily the exhibition is accessible online, bringing the works of this remarkable photographer to the fore.

LOVE spoke to Ming about her inspirations, intimacy and what she learnt from the power of the lens.

LOVE: There is such a sense of intimacy and connectivity about your images. How do you capture that? What do you look for in your subject matter?

Ming Smith: Well, there are stereotypes of the Black community, and there is so much love in the community, from people who were making and doing the best spiritually or going to church. There was just this stereotype of black people, you know, and I never saw those types of images with the love and the empathy and the humanity with the people that were around me in my community.

LOVE: You have become renowned for your portraiture of Black cultural figures and icons. What did you hope to profess or present in these images?

MS: I hope that other young people or students will find inspiration in what these images teach: the struggles of what they went through to get to where we are now. For example, take August Wilson: I went to Pittsburgh and photographed his home town and the economically depressed neighbourhoods, and shot some of the places he talked about in his plays. He documented the comic and the tragic aspects of the African American experience in the 20th Century. The characters in Pittsburgh were the same characters that I knew in Ohio where I grew up, or Detroit, where I was born.

LOVE: What would you say the main challenges you have faced in your career?

MS: I would say being taken seriously. I am a better photographer than a talker. I am quiet, and I like that with photography you can be by yourself, you don’t have to talk. Being shy, photography was a way of me being connected but out of it at the same time. If you are a quiet person it's harder to take you seriously.

I remember I went to a gallery seeking representation, and the galerist hardly even looked at my photographs; it was very disappointing. Just like “ok, thank you”. Just total dismissal.

LOVE: Did you have alot of other female counterparts and friends that were experiencing the same in the art industry or the creative industry?

MS: I am sure there was, and I’m sure there still is, but I have really continued to be a loner and doing photography was almost like a friend or a companion, and was how I spent my time. Being a photographer was a way of expressing yourself and going through your own challenges, and needs, and so I spent my time not really talking to anyone else.

LOVE: Did you feel inspired by the creative scene in New York?

MS: Definitely! All of my friends were. In New York I never knew about fashion photographers and advertising: it was a completely new world. I had a chance to go into both of those worlds, as I was modelling. I met people like James Moore who was a beauty photographer, to Debbie Turberville, who I loved. She photographed my lips for a Bloomingdales bag! She did fine art photography besides that; I really liked her. I lived in the Village, so I knew Lisette Model, and I would go eat at this little dinner, the Waverley - the cheapest diner. You could buy a meal for five dollars there, and that was where Lisette Model would eat too! She would tell me stories about Diane Arbus, and she would call her Dion. For the longest time, I didn’t realise she was talking about Diane Arbus as she called her Dion!

LOVE: You were part of the Kamoinge Group: did you feel like things in your life changed then, now that you were a part of a group of like minded individuals?

MS: It was at the Kamoinge Meetings that I was first introduced to photography as an art form. I had not committed myself to being an artist. When I was in college, I took a photography class, and asked the teacher what could you do with photography, and he said you could go into the photography of machinery, or medical. Both of those didn’t interest me. I didn’t think of myself as a photographer as I was still studying pre-med curriculum, but being part of the Kamoinge workshop really opened my eyes to this way of thinking. Roy DeCarava was one of the founders of Kamoinge, which came out of the Black Arts Movement. I was invited into Kamoinge by Louis Draper. That was when I first learned about the goal of Kamoinge: to own and interpret our own images.

LOVE: Why did you start painting on your canvases?

MS: I have painted on my photographs since 2000, and it has never really stopped. I don’t know why I started, it just felt like a natural thing. People used to describe my work that it had a very painterly quality. I think that even in photographing, I have been dealing with the light and the colours and black and white and the different tonalities. I would try and photograph light as a painter. It was almost a natural step: I wanted to add something else to it and it just came out of my instincts.

LOVE: What do you hope viewers take away from your works?

MS: I think just the personal struggles, the empathy or the humanity or the altruism or just being supportive. Maybe the humanity, and that being exposed to the people I have photographed, they will know what to do. I hope for other young artists, there is something there. That they get what they get from it: hopefully an experience that will inspire them in some kind of way.

The exhibition of Ming Smith at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery is online until 25th July.