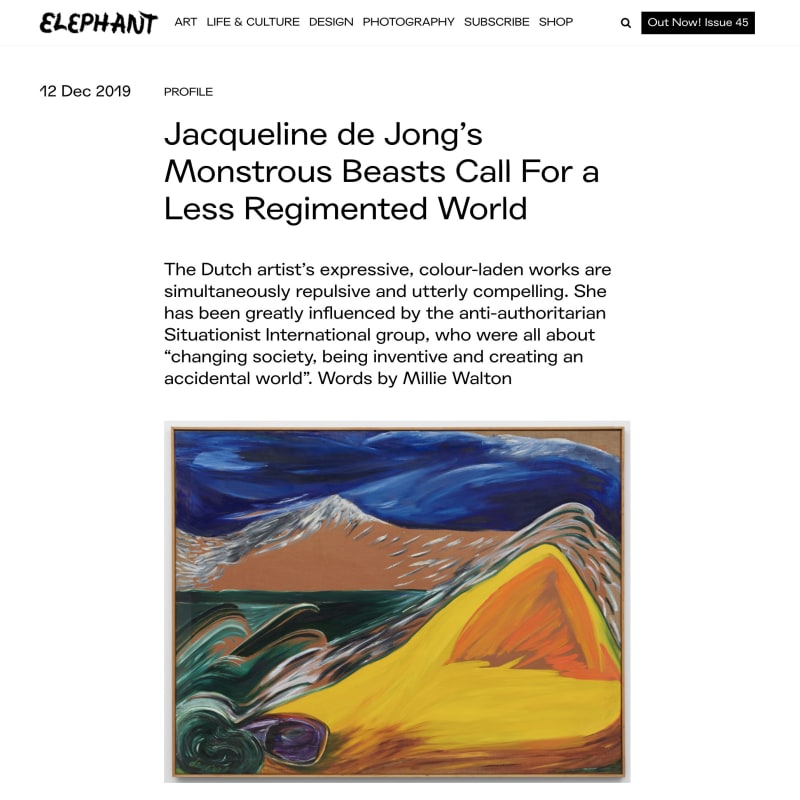

Standing in front of a series of paintings by Dutch artist Jacqueline de Jong, currently on display at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in Mayfair, I’m struck by something. Not so much by the artist’s surreal monstrous creatures or the searing colour palette—though both these elements are striking—but by the way the paint seems to be sliding across the canvas. It reminds me of a bunch of eels I once saw writhing in bucket at a market in Thailand. In the same way, the paintings are simultaneously repulsive and utterly compelling. It’s the urgency of a life force that pulls you in, that glues you to the spot.

“Why should everything be available all the time, day and night for everything and everybody?”

De Jong has been making work for over six decades, but it isn’t until now at the age of eighty that she’s beginning to garner international recognition. It’s significant, for example, that this is her first ever solo show in the UK and that she’s generally received less institutional attention than her male contemporaries. However, Yale University’s acquisition of the archives of her radical magazine The Situationist Times in 2011 plus a major retrospective at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum earlier this year are markers of a growing interest. “I just did my work until now and took whatever opportunities came my way,” says the artist. “I think everyone is suddenly in a hurry because of my age. They don’t want to miss the moment.”

We’re sitting in the lounge bar of her London hotel, which on an especially blustery early winter’s evening is already heaving with people. De Jong speaks energetically, letting the conversation run in chaotic directions before pulling it back together again at the last minute. The person behind us was on her plane over from Amsterdam, she observes, offering me a sip of her Coca-Cola and then continuing with an anecdote about live-painting at a friend’s fashion show with barely a breath in-between: “I had absolutely no idea what I was doing, but I was lucky because the first drawing on the canvas went well.”

This spontaneous approach idolizes rawness, fluidity and the unexpected, but De Jong admits that it doesn’t always work out, and by that she means “it doesn’t feel right”. “There’s one painting in my studio at the moment and whatever I’ve done to it over the years has always gone wrong. But then yesterday, I did something to it which made it okay, and I thought, ‘Oh my god, I’m going to have to go on’,” she says. “Sometimes, of course, you have to stop otherwise you get completely frustrated with your own work, but it’s hard to stop.” It feels like an apt time to ask about the title choice for her current show: Resilience(s). She laughs, “The name comes from a book I saw by Philip Guston, who I admire very much, but I thought that I shouldn’t pinch his text so I changed it by adding the ‘s’ and the brackets. I like that the word has several meanings. I think that titles give the artworks another layer of meaning.John Chamberlain, for example, very often used text from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which hardly anyone knows because so often the titles aren’t displayed with the works, but it’s so important to have the intellectual context of the artist.”

Regarding significant contexts for De Jong’s work, it’s impossible to ignore the artist’s participation in the anti-authoritarian Situationist International (SI) group. Though not an artistic movement, the group and its members greatly influenced and inspired her practice. “I liked what the Situationists were talking about,” she says. “It was about changing society, being inventive and creating an accidental world, one which is less regimented. I remember going to an exhibition by some of artists involved, and they had painted the whole gallery from top to ground and nothing was for sale.”

“Artists are judged on their place in the market, and I find that kind of judgement very frightening."

“Another thing that sets de Jong apart is her persistent belief in the surreal capabilities of the imagination”

Interestingly though, De Jong isn’t anti all limitations. She tells me, for example, that she very much “dislikes how people are putting images on Instagram all of the time”. “Why should everything be available all the time, day and night for everything and everybody? Do people actually want this?” she continues. “That’s more or less what I think about the art world. It’s too diverse, and it is, of course, very nice that it’s diverse, but you have to remember that art doesn’t change climate problems, it doesn’t change Trump problems, it doesn’t actually change the world.” It’s important to note here that her concern is not with the possibilities provided by technology, but more with the way apps like Instagram are changing how images are consumed and integrated into a system whereby the validity of an artwork often equals the number of likes rather than artistic merit.

Interestingly though, De Jong isn’t anti all limitations. She tells me, for example, that she very much “dislikes how people are putting images on Instagram all of the time”. “Why should everything be available all the time, day and night for everything and everybody? Do people actually want this?” she continues. “That’s more or less what I think about the art world. It’s too diverse, and it is, of course, very nice that it’s diverse, but you have to remember that art doesn’t change climate problems, it doesn’t change Trump problems, it doesn’t actually change the world.” It’s important to note here that her concern is not with the possibilities provided by technology, but more with the way apps like Instagram are changing how images are consumed and integrated into a system whereby the validity of an artwork often equals the number of likes rather than artistic merit.

Significantly though, Resilience(s) focuses on a collection of paintings made predominantly during the 1980s rather than her more contemporary work. De Jong says she was surprised but pleased with the gallery’s selection: “They are diverse, but quite current I think.” Take, for example, the large-scale painting humorously titled Big Foot Small Head (for Thomas) (1985), which was created for Amsterdam’s city hall. The painting depicts an angry-looking man with a dagger in hand, trampling on a reptilian creature as he descends a staircase. The intense hues, urgent brush-strokes and palpable tumult in this painting, and the others, seems to speak if not of our times, then certainly to them.