In recent reassessments of the art of Jacqueline de Jong, emphasis has been placed on the overlooked Dutch painter’s early involvement with the Situationist International, as well as her relationship with Asger Jorn, her mentor and romantic partner in the 1960s. Both associations clearly played important roles in her development. By the latter part of the ’60s, however, de Jong had swerved away from the elder artist’s influence. While they share a certain dérèglement with Jorn’s drunken berserkers, her chimerical figures evoke a polymorphic perversity; as with those of her compatriot Hieronymus Bosch, their liberatory zeal veers toward the monstrous and carnivalesque.

I first encountered her work at this year’s Frieze Art Fair, where Pippy Houldsworth mounted a small showcase of late ’60s de Jongs. There, in an improvised palette of fluorescent pinks and sky blues, fragmentary limbs in candy-striped stockings were entwined with troll-like men with phallic, cyclopean heads in an atmosphere of cartoonish debauchery. Removed from their political context, the paintings more than held their own. (Expelled from the official cadre in 1962, de Jong later founded the breakaway Situationist Times, which she edited throughout its five-year existence.)

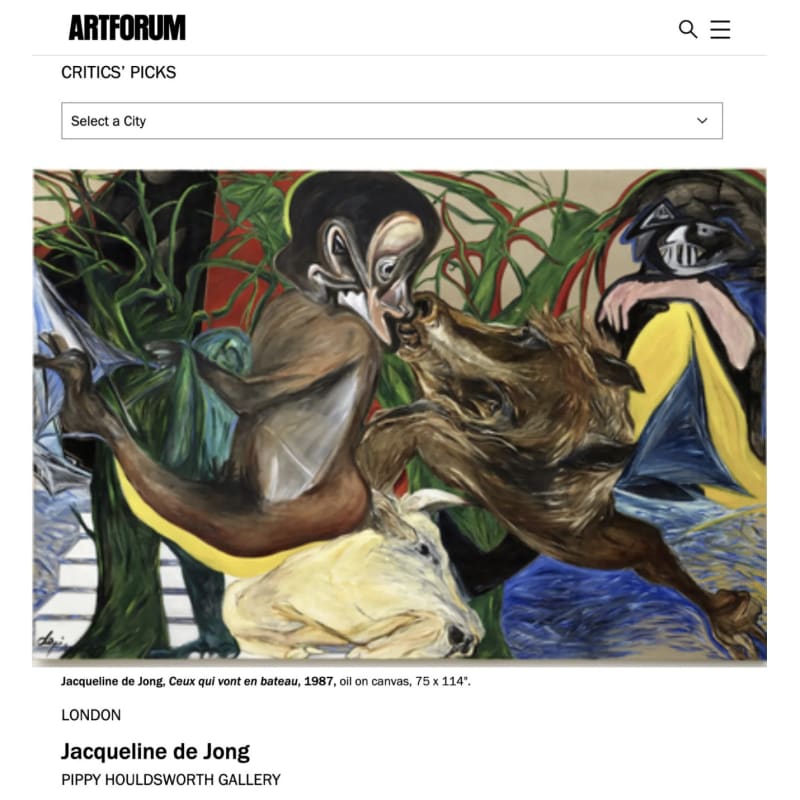

If the pictures at Frieze evoked an urban imaginary, merging busy street with crowded boudoir, in the works on view here, all from the 1980s, the artist offers up a vision of nature saturated by the memory of various Expressionisms. Francis Bacon’s late ’50s series made in homage to van Gogh has clearly inspired de Jong’s palette: ripe greens and yellows, dark reds and blues are dragged across beige grounds left unprimed. While her ’60s canvases deconstructed the street-interior dyad, here the recognizably human edges toward its opposite. The mounted hominid in Ceux qui vont en bateau appears to be locked in a kiss with a toppled horse, and in Passage de Paysage (both works 1987), an angular hiker could be the spiritual emanation of a gnarled, gothic tree.

— Patrick Price