Throughout the 1960s, Ringgold produced politically charged paintings that shattered the notion of the American dream, highlighting the racial and gender inequalities which are rife in society. Rendered in a style that synthesises post-Cubist Picasso, Pop Art and traditional African sculpture and design, the figures in these paintings reflect the tension arising from interracial contact and the psychological substructure of racism in everyday life, a far cry from the utopian aspirations of the civil rights movement happening at the time. The flat planes of colour and thin glazes of paint speak to the influence of Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden upon the artist’s work.

From the early 1970s, Ringgold was instrumental in organising protests that called attention to the lack of opportunities for women of colour in the art world. Focusing her attention on the Whitney Annual, Ringgold demanded that 50% of the artists should be female. In 1971, she set up Where We At, Black Women Artists, Inc (WWA), a collective of black female artists who felt neglected not only by the mainstream but also by the male dominated Black Arts Movement and the largely white Feminist one. Ironically, many years later, Ringgold’s work was recently on display at the Whitney Museum in An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection (2017-18). In addition, the collective efforts of these female African-American artists including Ringgold were the subject of a recent exhibition at Brooklyn Museum, New York title We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85, which travelled to the ICA Boston and Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo (2018).

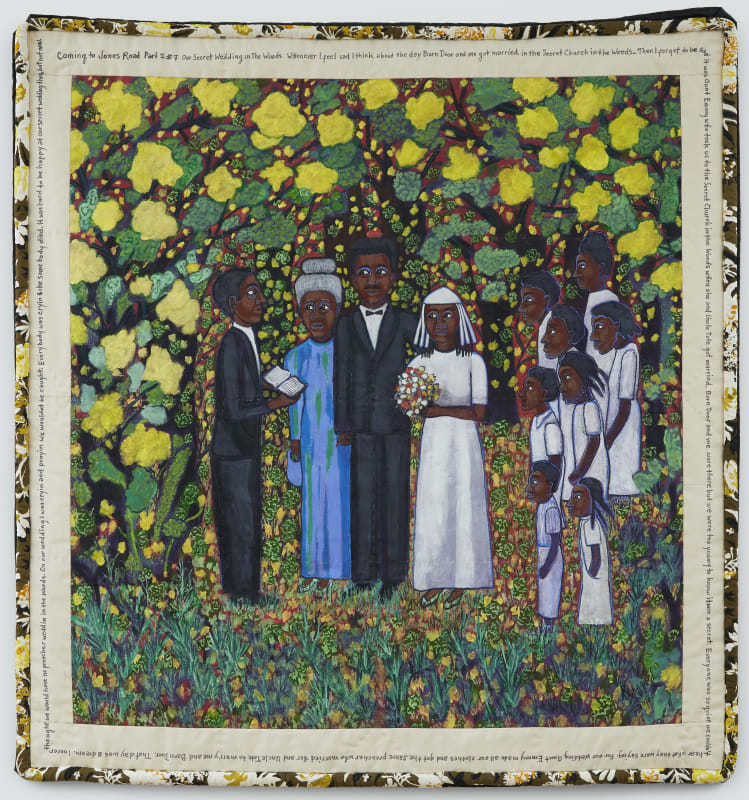

In the 1980s, Ringgold shifted her tone, moving away from the explicit works of the previous few decades. At the time, the artist was looking to appropriate a medium that was historically associated with femininity, yet could be implemented for subversive means. In 1980, Ringgold collaborated with her mother Willie Jones, a fashion designer and dressmaker, on her first quilt, Echoes of Harlem (1980), now in the permanent collection of the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. This proved to be a formative experience for Ringgold. Tapping into the rich tradition of African-American quilt-making, and combining it with her love of European painting and the written word, Ringgold went on to develop her now legendary 'story quilt' technique. That the artist's great-great-grandmother Susie Shannon was born into slavery and produced quilts for plantation owners lends Ringgold's work a deeper, personal resonance.